Ethnicity is one of the most slippery topics in Hollywood. The first two Latin actresses to do the crossover were Mexican Dolores del Río (1904-1987) and Lupe Vélez (1908-1944) during the silent film era. Both embodied the image of a mute Latin, but from different angles, beyond the “exoticism” radiated by their respective figures.

Vélez was the “mean wild Mexican cat” and Del Río the “good Spanish lady,” a decision conditioned by the Anglo constructs then in force. “Anglo-Saxon perceptions of Spanish and Mexican women in 19th-century California,” argues one study, “were based on gender, race, and class. Both stereotypes revolved around sexual definitions of women’s virtue and morality.… Elite Californian women were seen as European and superior, while mass Mexican women were seen as natives and inferior.”

If the majority of Mexicans were assumed and represented in the narrative as racially inferior beings, the landowning women united with Anglo-Saxons were represented in a positive way, both in society and in the movies of that time. They were, in effect, the “good Latinas.” The others, to say the least, were seen and represented on the screen as vulgar, femme fatales, sex in its purest form, an attraction made for the heterosexual consumer in a world marked by the traces of that foundational puritanism that would start being challenged in the “roaring 1920s,” in particular by jazz club flappers and Prohibition speakeasies.

But this conditioning of the image of Latinas would not be exempt from the policy, in particular that of the Good Neighbor, advanced for Latin America by U.S. President F. D. Roosevelt after a prolonged period of military and gunboat interventions. Their portrayal par excellence on movie theater screens was not strictly a Latin American woman, but a European, emigrated to Brazil: the Portuguese Maria do Carmo Miranda da Cunha, better known as Carmen Miranda (1909-1955), the Bahian.

It was a rather sweet proposal, but empathic, full of colors, tropical fruits and exotic music, particularly samba, a rhythm that the actress contributed to spread powerfully throughout the U.S. culture of the time and that would end up opening greater spaces for Latin culture on which other actresses and actors like Desi Arnaz and Anthony Quinn and even Pérez Prado’s mambo settled down, an epidemic that in the 1950s was called mambo craze.

A counterexample to the first trend is Margarita Carmen Cansino, documented in film records as Rita Hayworth (1918–1987). Born in the New York Bronx to a Spanish father and an American mother of Irish descent, Hayworth was whitewashed by studio executives until she was made a WASP. She came to this after the film In Caliente (1935) — by the way, with Dolores del Río — and after a process in which she played, indistinctly, the roles of an Argentine, Egyptian or Russian girl.

The studio executives argued that her figure was too Mediterranean and that this would only be enough for her to play small ethnic roles. And her last name, of course, was “too Spanish.” It was then that the bombshell was born, first with red hair and then blonde, the one that captivated several batches of Americans and that would serve as a paradigm for new wave actresses such as Marilyn Monroe (1926-1962) and Jayne Mansfield (1933-1967).

Hayworth was the very image of sexuality and the femme fatale as of the film Gilda (1946). The most desired woman in the world. “The Hollywood Goddess of Love.” “All the men I know sleep with Gilda, but they wake up with me,” Hayworth once said. She had an intense cinematographic life sharing leading roles with actors such as Frank Sinatra, Cary Grant, Tyrone Power, Gene Kelly, Fred Astaire, Robert Mitchum, James Cagney, Glen Ford and Orson Welles, one of her husbands, who gave her the leading role in The Lady from Shanghai (1947).

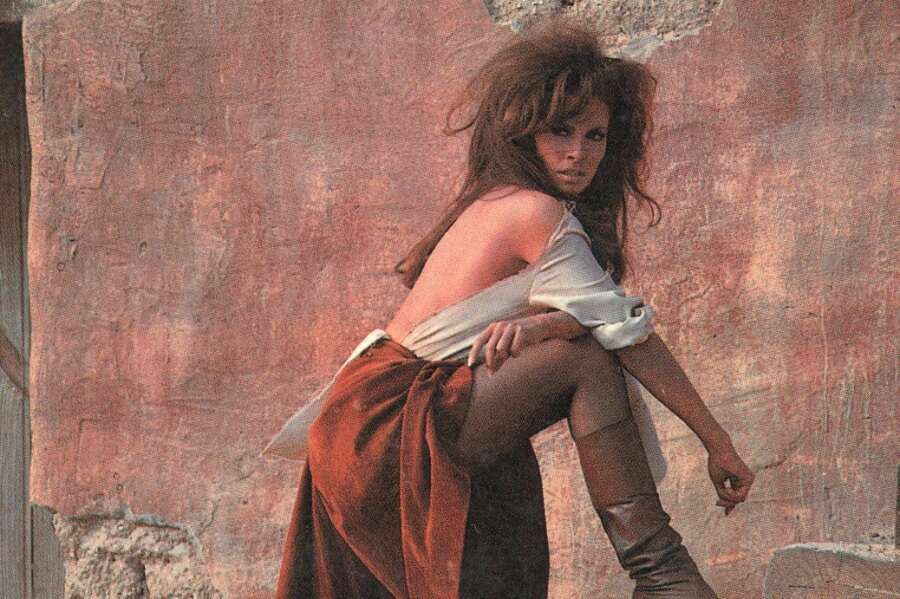

But sexuality had come to stay with the entrance to the celluloid world of actress Jo Raquel Tejada, better known as Raquel Welch (1940). She did not debut holding Mediterranean, Hispanic, or ethnic credentials, but rather as an expression of a phenomenon called melting pot. Born in Chicago, the daughter of a Bolivian engineer and an American of British origin, Welch was, without a doubt, one of the most powerful sex symbols of the 1960s and 1970s.

II

Currently, the entrance to Hollywood of the Cuban actress Ana de Armas was not marked by ethnicity, that is, her status as Cuban/Latina did not determine her inclusion in the cast of the film Knock Knock (2015), a psychosexual thriller by director Eli Roth with Keanu Reeves in the lead in which she plays Bel, one of the two co-stars in the story (the other is actress Lorenza Izzo in the role of Genesis). Her first film in that position was Exposed (2016), in which she played a Puerto Rican woman who is raped (Isabel de la Cruz) alongside Keanu Reeves himself.

Then in War Dogs (2016) she played a non-Latin supporting role as Iz, the wife of an arms dealer, but in Hands of Stone (2016) she played the wife of Panamanian boxer Roberto Durán in a film starring Robert DeNiro and Rubén Blades.

The following year came Blade Runner 2049 (2017), in which she also played a supporting role, albeit a powerful one: Joi, the protagonist’s holographic girlfriend. The film featured performances by Ryan Gosling and Harrison Ford. Here, De Armas was able to continue in the footsteps of Knock Knock and War Dogs, in which she learned her lines phonetically since she did not master English well enough. One critic wrote about her work: “The warmth and optimism she [Ana de Armas] brings to the screen were essential to the film’s success. This makes seeing her acting in this film a must for those who don’t know her work.”

A little later was Overdrive (2017), by director Antonio Negret, the story of two car thieves where she plays the girlfriend of one of them (Andrew Foster, characterized by Scott Eastwood), a film that went unnoticed through the box office and critics. A year later, she would play “ethnic” roles again in Corazón (2018), a bilingual venture by director John Hillcoat, in which she plays Elena Ramírez, a Dominican prostitute with a heart condition. Yesterday (2019), by Danny Boyle, was a conventional romantic comedy.

But there were two films that, without a doubt, placed De Armas in a qualitatively different place, again following the trail of the “ethnic.” The first, Knives Out (2019), by director Rian Jonhson, a detective story structured on the death of the novelist Harian Thrombey, in which De Armas plays the role of his nurse of Ecuadorian origin, Marta Cabrera. She wasn’t literally a leading role, but she was able to hang out with actors like Daniel Craig, Jamie Lee Curtis and Christopher Plummer. And in fact, due to her very important role in the plot, her character went beyond being a “Latina caretaker,” a fact that led her not to reject the character after a careful reading of the script. If Blade Runner 2049 put the Cuban actress on the radar, Knives Out was an international success that would earn her a Golden Globe nomination. And that earned her the award for Best Supporting Actress at the Saturn Awards.

In the second, No Time to Die (2021), she plays a role specially designed for her by the film’s director and co-writer, Cary Joji Fukunaga. There she is a “Bond girl,” the second actress of Latin origin to be one after New Yorker Talisa Soto (1989), and she embodies the character of Paloma, a Cuban CIA agent involved in spectacular actions in Santiago de Cuba together with to the eternal 007 (Daniel Craig), created more than half a century ago by novelist Ian Flemming. It wasn’t a leading role either (just 15 minutes on screen), but it earned her a nomination for best actress in an action film from Critics’ Choice Superawards.

A Latina playing an icon of American culture, such as Marilyn Monroe, is unprecedented in Hollywood history, at least as far as I know. That is precisely Blonde (2022). Selected by director Andrew Dominik and producers such as Brad Pitt, and with the endorsement of actresses such as Jamie Lee Curtis, in her first leading role in Hollywood, Ana de Armas took on the enormous challenge of embodying a living legend with the peculiarity of succeeding, apart from the limitations of the script and the direction of a film weighed down from the beginning by its ideological assumptions.

The film marks the transition from actress to star, but her outstanding work does not authorize her to be considered “the best Latin actress of all time” just because she is the first Cuban with the potential for an Oscar nomination. Affirming it means ignoring a history of more than a hundred years, ignoring the presence of screen divas such as those noted at the beginning (among others), and even the future acting roles of Ana de Armas, who has plenty of time, all the time.…