Eduardo Abela Torrás (Havana, 1963), who lives and creates in Havana, is the son and grandson of renowned visual artists who left an imprint in Cuban art. However, the third Abela revealed himself early on against his genetic condition and, although he always drew in his school notebooks and almost became “the classroom’s scribe,” he refused to follow his father’s and grandfather’s steps; at the time he wanted to be a musician “to dissociate myself from my legacy.” He thus opted for humor. He worked for publications – like DDT, Palante, Bohemia and the newspaper Tribuna de La Habana – where he found the space for his first works. But genetics doesn’t fail: “although I greatly enjoy humor, I sincerely never came to believe in it,” he confesses to OnCuba.

When in the late 1980s Abela got to the prestigious San Alejandro Art Academy he was already cultivating a work linked to graphic humor. Since that specialty has guidelines and rules that must be respected, he felt that engraving would give him the tools to become a designer, which was his intention: “I didn’t want to be a painter. It was a battle I waged against myself,” he affirms.

For his graduation thesis from the Academy – which he defended in 1991 – he approached the Havana Experimental Graphic Workshop, the one in Cathedral Square, and there, he confesses, his life changed: “I met Pedro Pablo Oliva, Roberto Fabelo, Nelson Domínguez, Zaida del Río, Pepe Contino, Botalín, Eduardo Roca Salazar (Choco), among other creators, and it is then that I really started entering and understanding the world of the engravers. Although I continued doing caricatures, I started seeking other forms, other projections, and I suppressed the texts and they almost turned into illustrations. The Engraving Workshop completely opened my horizons and I mutated from graphic humor to the visual artist I am today.”

Abela has had numerous and diverse exhibitions throughout his intense career, but what’s significant is not the amount but rather that in each one of his proposals he presents and defends a thesis: “I display when I have something new to say; each exhibit has a defined and marked purpose.”

Fundamentally figurative and a disciple of the work of Cuban painter, engraver and sculptor Angel Ramírez, who today he still considers “his teacher,” Abela remembers with particular pleasure some projects with a two-person exhibition in 1998 in La Acacia Gallery with the also – abstract – painter Andy Rivero: “our works have nothing in common, but we were joined by themes because they were appropriations and also humor. Andy took from Mondrian and Modigliani, and I from Keith Haring Lichtenstein. Both languages were incredibly imbricated and seemed works by a single person. A stew thickened, but based on graphic art as sustenance because both of us are engravers.”

In 2004 in the Servando Cabrera Gallery – together with Ernesto Rancaño and Vicente Rodríguez Bonachea – he exhibited Un, dos, tres… que trazo más chévere, and that same year in the venue of the National Council of Visual Arts the one titled Las once mil vírgenes, while in 2005, in the Palace of Count Lombillo, in colonial Havana, ¡Ay, Dios mío!

In Mecánica popular he tended to favor the object: “I like the tridimensional and I had been doing an object-style work with textures.” That taste for the object and even for the arte povera – his works take out of oblivion certain objects that have had other lives – is also a support in Abela’s work: “another of my great passions is collecting antiques – old typewriters, telephones, receptacles, etc. -, and that allows me to have a stock of objects that open another road for me, because I get tired very fast with what I’m doing, although I have doubts, I don’t know if that is a virtue or a defect. Artists generally work a line until they seek – and even find – that which they call their own seal, but personally I am absolutely not interested.”

U.S. photographer Richard Falco’s snapshots on September 11, 2001 in the site where the Twin Towers in New York were served as inspiration for the work of 42 Cuban artists to order. The exhibit, displayed in Havana’s José Martí Memorial, was titled Cita con ángeles and Abela was one of the chosen creators: “I assume that type of work as a challenge. I love to submerge myself in worlds I have never explored and to exhibit together with artists that have made incursions into certain themes. Even though I miss a risk, it’s a way of measuring oneself. There are artists who when they get to what I call ‘the comfort zone’ settle themselves and become stagnated. That’s something I really am afraid of and that’s why I am constantly placing self-traps for myself and making incursions into the most diverse materials.”

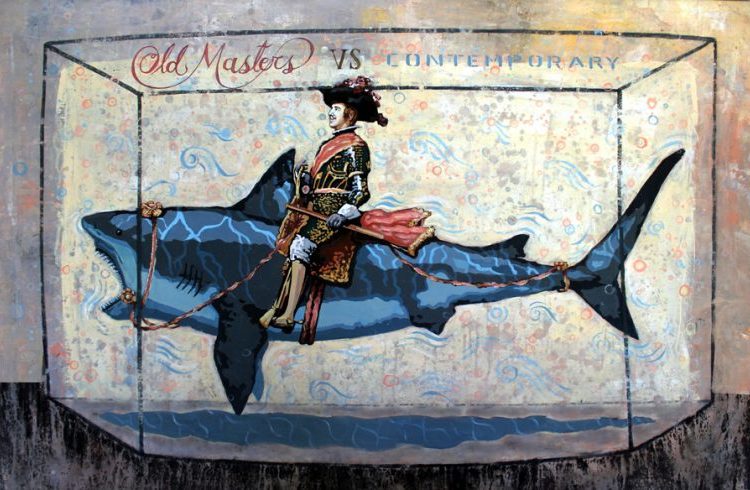

In 2014 the spacious El reino de este mundo Gallery, in Havana, hosted Maestro, ¿pudiera usted explicarme? in which he proposed a dialogue between contemporary art and the most traditional: “contemporary art is advancing at a great speed and what before was rubble is now an installation. Today art is very free and the barriers of what is or isn’t art are vague, they even don’t exist. In that exhibition I worked on established aesthetics – like those of Rembrandt or Velázquez -, that is to say, on the most classical currents; it was the dialogue or confrontation between the art that is institutionally considered good art, and the other new one, which challenges what has been imposed for centuries.”

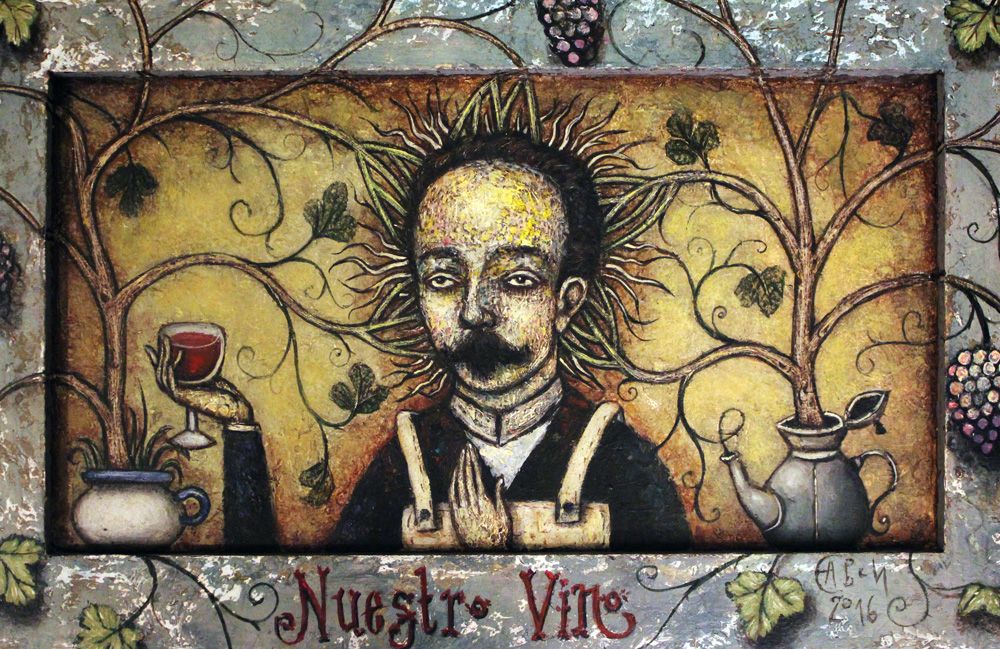

As Abela confessed, his painting delves into Cuban identity, but in a sui generis way. These are some of his arguments: “I speak of identity because I work on aesthetics that are not Cuban and the Cuban is in what happens, in the story told in each work. Frequently the particular is the universal and that’s why I work a great deal with traditional music, with the history of the nation. My iconography has to do with the pop or with the gothic, but what is narrated is purely national. My essence, or heart, is absolutely Cuban and the exterior covering is just a pretext,” he concluded.