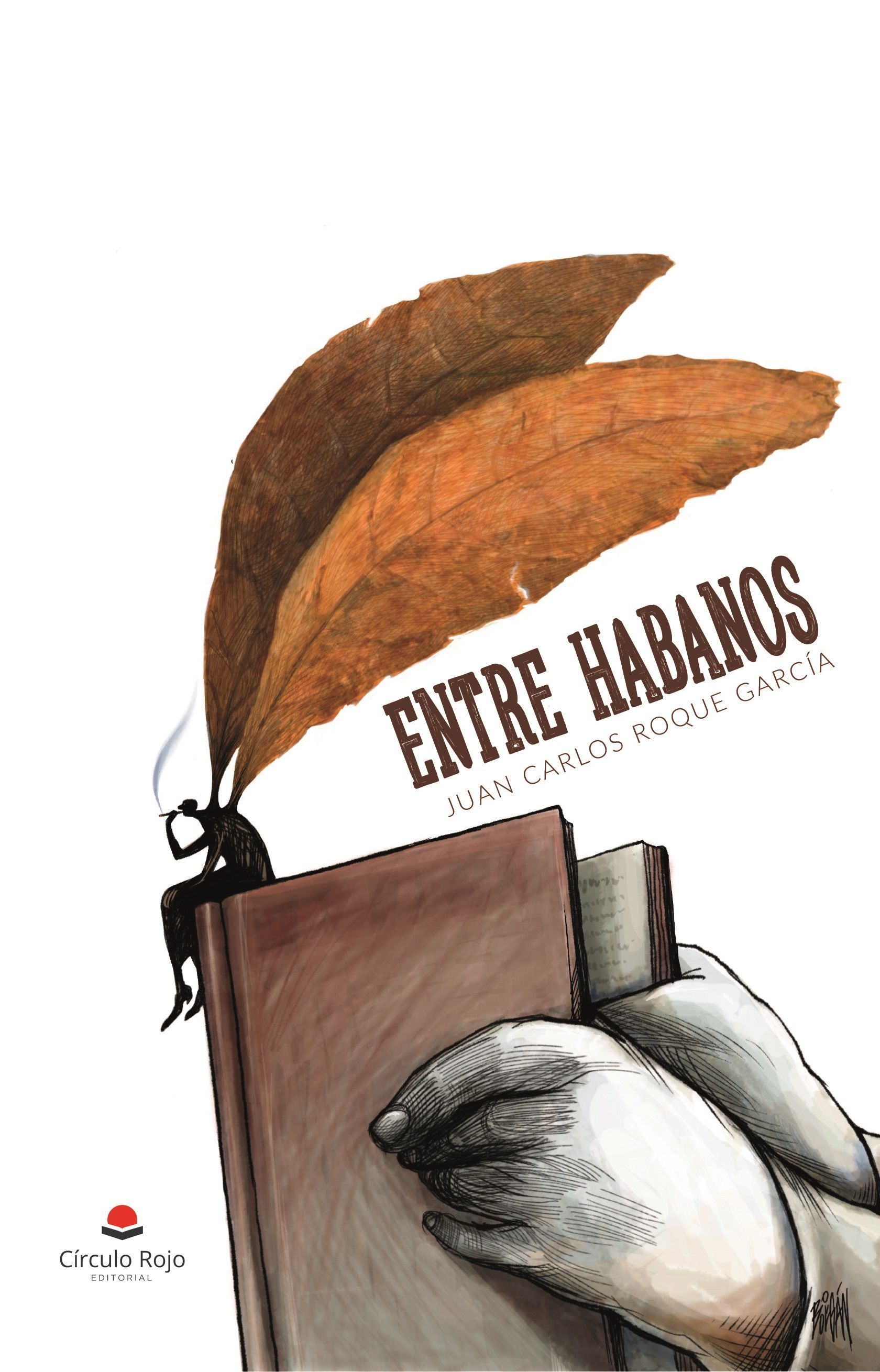

Juan Carlos Roque García (1960), who is an absolute man of radio and whose voice internationalized Radio Netherland, that oasis that we heard at some time, wrote and has just published a novel titled Entre habanos (Among Cigars, Círculo Rojo publishers, 2019).

His argument unfolds in the late 1970s and extends until the mid-1980s, specifically between 1979 and 1985, seven years like the seven letters of the word “habanos,” that kind of acronym with which he presents to us the index at the beginning of his book.

A factory as a context is something that I do not believe often appears in contemporary literature; in Cuban works, for years I have had no knowledge of a “worker” background, if you want to call this way the concatenation of events that have as a starting point or end a workplace.

And that the repetition of “production process,” “better tobacco” or “export” in some parts for me became the first challenge as a reader, since the only reiteration of the words “cigar factory” or “cigar,” that element that Fernando Ortiz called “haughty” and with aspirations to be “puro” [in Spanish this word is used to mean pure or cigar] ended by transforming me into a true tightrope walker who tried not to fall into the void I believed was below.

A novel about the life of cigar makers can be risky. On the one hand I could expect the folklore descriptions of the tourist guides and on the other the optimistic reports in the press, because the author props up his story by mixing literature and journalism; not by the use of the language itself, but by the distribution of fragments of literary works or press reports to unravel in this way the drama of his characters (Paca, Dani, María Trinidad, Julia, Manolo, Ignacio….), cigar makers, factory workers, dissimilar in their way of behaving as sexual, social or political beings, although united by the cutting knife, the table and even certain moral standards.

As can be inferred from the title, the dialogues gain extreme importance in what is Roque’s first novel, set in Güira de Melena, Artemisa, his native land. Through them the facts are unleashed; or the facts unleash the dialogues, condition them, which I will explain.

One of the ideal exercises related to a cigar, even being away from any cigar factory, is conversation: communication between friends, relatives, lovers, neighbors, co-workers, bosses and subordinates. Maybe that’s why the verbal exchange in the middle of work or in private takes on the importance of another character in these 212 pages.

But, sometimes it could also be understood as the deaf dialogue of the people with the government, because Roque’s characters, who represent ordinary people, also called “common,” at times seem to speak to the leader who does not listen, to the Power’s hammering of its doctrines through the press, incorporated here almost all the time as the official and definitive opinion.

It happens from beginning to end, exemplified in some key passages, and in others not so important for the development of what is said. It is the “official story” that is repeated to speak, for example, of the events that occurred regarding the Peruvian embassy that led to the Mariel exodus, the outbreak of hemorrhagic dengue or the invasion of Grenada….

The “official news” becomes paramount both in Cuba and in this novel, and the universe of a cigar factory offers the possibility of demonstrating it as in no other scenario thanks to the fact that this prehistoric and esteemed trade is still there: the cigar factory reader.

This function is embodied by Ignacio, whose conflict becomes key in what could be the philosophical prop of the story, which has its magnificence in a final scene, of course not revealed here. I only add that as a strong metaphor there is Marx’s hollow book, turned into an object of contraband; however, on the other hand it confirms the moralistic behavior of most of the characters, too good, too honest because they perhaps have an established idea of society understandable only if lived in one of those years in which the story takes place.

Here the cigar factory reader, moreover, is sometimes like the chorus of Greek tragedies, the collective voice and the counterpoint between propaganda and social awareness, somehow turned into literature through the fragments that he chooses to share daily.

Novels by Shakespeare, Alexandre Dumas, Carpentier, Jorge Amado or García Márquez are alternated with forceful editorials, news or excerpts of Fidel Castro’s speeches published by the daily Granma; literature complementing the journalistic reality, the characters of real life feeling what the fiction characters feel, wanting to be like them. But, it is in reality where, as is said, they again collide with the truth.

Roque uses this technique of gathering press releases, fragments of novels and dialogues created by him to review forgotten events, people or conflicts that range from the fall of a Cubana de Aviación airplane to the homophobic chapter of the Revolution summarized in those Units to Aid Production (UMAP), where one of the characters, Dani, had ended, and who will have no other path than to leave the country, leaving taking advantage of a moment that the government has brought about.

There is a phrase quite repeated in Entre habanos: “life follows its pace,” an expression that although said by the narrator is always in the minds of the characters, who, by the way, give the impression of living for History and not for themselves; each step, each action, each movement has the function of unleashing a greater movement, alien to themselves even if they are the ones who let it happen.

Perhaps, this is one of the most catastrophic interpretations I can make after reading the novel: life goes on, it continues unstoppable, and we Cubans have never lived for ourselves, but for something that is higher and that, in the long run, crushes and disallows individualities.

Entre habanos owes a lot to the radio, not only because its author is to this medium like a transistor to the broadcasting equipment, but because it is written almost in a radiophonic way, like those radio soap operas that are still broadcast on certain stations and that have the quality of maintaining the listener’s attention. It can be noticed in the time in which it is narrated, in how the chapters are divided, in the way of presenting the characters or sometimes in the overabundance of data.

Juan Carlos Roque has already published several books, one of them, Nunca me fui, a testimonial text that addresses in first person the issue of emigration. Now, with the eye of the man who was young in the Cuba of the 1980s, since 1995 he has been living in the Netherlands, he reconstructs with fiction an era that was also essential for him. In this way he awakens his ghosts, checks his obsessions and wants us to take sides despite him and his circumstance.