In the second half of the twentieth century, an illegally unknown writer, Raoul Delorme, founded the sect or movement of the Barbarians Writers. Until recently I had never heard of him. Now, suddenly, it seems he is everywhere.

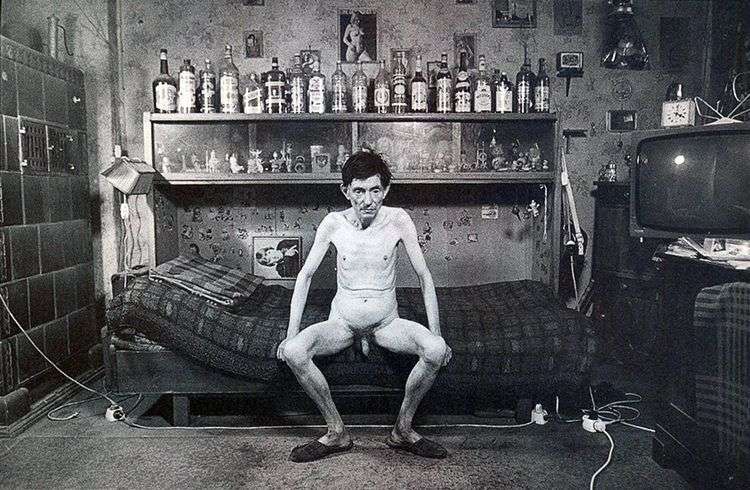

To begin, someone gave me a copy of the Revista de los Vigilantes Nocturnos de Arras (a magazine published , indeed, by a corporation of night watchmen) which contained a quite illustrative and meticulous barbaric anthology. Texts by Delorme appeared under the subheading Cuando la afición deviene profesión. A minor poet, I thought, without the necrosis of the Belle Lyrics. Then, two or three days later, I read his article-manifesto entitled La afición a escribir, which gives shape to his new literature. According to Delorme we had to merge ourselves with the masterpieces. This was achieved in a most curious way: defecating on the pages of Stendhal, masturbating and spreading the semen on the pages of Gautier or Banville, vomiting onto the pages of Daudet, urinating on the pages of Lamartine, making cuts with razor blades and splashing blood over the pages of Balzac or Maupassant; finally, subjecting books to a process of demystification and closeness that broke all barriers of culture, academy and technique.

I loved it. I liked it so much that I read it three times. Who is this Raoul Delorme? I wondered, and where has he been hidden? How a guy with such a ridiculous age (Delorme was thirty-three when he wrote the book) had managed to make such a perfect work? Because it must be said: La afición a escribir is a treatise of more than five hundred pages about the anguish of literary influences. And in its interior you may find things like: “The writers all, either by historical habit , fate or by own choice, are always cannibals: they devour each other . In general, they do not read the books: they eat them like Saturn to his children; their digestions are long and, in most cases, the risk is that the same force devoured satiates and nullifies them “. (This lucidity, in the sixties-a decade before the publication of The Anxiety of Influence, the highly publicized essay of Harold Bloom, it cost Delorme anathema and ” forgetting” of the called Yale School).

Similarly, Harold Bloom’s book is embarrassing to read as soon as you recognize that each and every one of the judgments that issues are reflections of La afición a escribir and the “theory of failure” by Raoul Delorme. The theory essentially postulates that the literary influence is based on the parent / child relationship. The precursor is the father, the son is ephebe. A child receives from his father the life, education, training of his character. But there is a point where the child should become independent, take charge of his destiny, gain his own identity. Otherwise, he runs the worst of the risks: not to exist as an individual, being just a shadow, a pale reflection of his father. Let us examine, almost at random, some examples of the “theory of failure.”

Among the stories of sons of famous writers whom are considered victims of the talent of their parents, those standing by the mystery that surrounds them, is the one of Lucia and Giorgio, sons of the author of Ulysses. Educated in the shadow of one of the modern masters of the form, Giorgio chose the music and Lucia opted for dance and writing. But they eventually succumbed to alcoholism and hebephrenia respectively. Let us take the second case: Lucia Joyce. Withdrawn and sickly from childhood, we know that Lucia did not write deliberately but induced by her father. Off by jettisoning his objectivity, Richard Ellman, one of the main biographers of James Joyce, not without emphatic and confusing arguments recklessly mixing psychiatric and literary aspects of the problem seems to accept the insane claim of the Irish author that only he is able to cure his daughter through the exercise of writing. Then, to correct that youthful neurosis, Joyce conceived Finnegans Wake, another application of psychoanalysis as a narrative technique. Joyce only showed once Carl Jung the texts of Lucia claiming that his daughter wrote just like him. It was also famous the opinion of Jung: “But where you swim, she drowns.” Lucia ended psychotic; only Samuel Beckett, who for some time was secretary of his father-and rejected her after having been her lover for a period of two years, and Harriet Weaver, editor of Joyce, visited her in the hospital of St. Andrew’s where she died as Anna Livia at the end of Finnegans Wake, “alone in her loneliness.”

Another vivid exponent of the “theory of failure” is Margaret Salinger, daughter of the famous JD Salinger. In The Keeper of Dreams, Margaret draws a sketch of her father in which the author of The Catcher in the Rye appears as a monster capable of the greatest signs of selfishness and cruelty, perhaps only comparable with the father of Kafka. Maybe it is enough to remember the beginning of the “Letter to father” by the writer from Prague to exhume those feelings:

Dear Father: You asked me once why I said I’m afraid of you. As usual, I did not know what to answer, in part, precisely because of the fear that I feel for you, and partly because the foundations of this fear include much details for you to keep them together in the course of a conversation. And even I try writing an answer now, my answer will be, however, very incomprehensible, because even when writing, fear and its consequences inhibit me before you, and because the magnitude of the subject exceeds my memory and understanding.

All these stories, among others to what could be added the names of the terrible spectra -so calls Delorme- by Arthur Miller, Kenzaburo Oe, Miguel de Unamuno and Pablo Neruda, are the arguments used by Raoul Delorme, not without credulity and enthusiasm. The book was so good, I thought, that surely was not recognized neither by critics, nor academies -by anyone. It was another great author that would die unknown or voluntarily “forgotten”. However, luck wanted Roberto Bolaño to “discover” him. I read about this “encounter” which then led to the novel Estrella distante. But the main thing was otherwise; which resulted in a discovery and a decisive event for me was reading a marginal annotation result of the thoroughness and the suspicion of Bolaño. In chapter nine in the novel it reads: “Next to the texts by [ Xavier] Rouberg (whom the editor of the Revista de los Vigilantes Nocturnos de Arras called the Juan Bautista of the new literary movement) [and Raoul Delorme] there were Jules Defoe’s texts “. When reading that little fact there was a strange revelation: the unexpected reference of an author as Jules Defoe, unknown, and who is probably an invention of Roberto Bolaño or a perfect pseudonym of Carlos Ramirez Hoffman (Santiago de Chile, 1950 – Lloret de Mar, Spain, 1998), one of the most conspicuous representatives of Nazi literature in the Americas.

Bolaño argues that the follower par excellence of the barbaric writing on Latin America is Carlos Ramirez Hoffman. According to Bolaño, however, Hoffman´s effort to consummate in our continent the pending revolution of literature (i.e. the barbaric deed) ends in failure. I believe that Bolaño is wrong, as in many other things as well as in many others, is probably the best Latin American writer since Jorge Luis Borges. It is true that gutting hundreds of books of Latin American literature doesn´t make an Argentine, Cuban, Chilean and Mexican writer, but certainly it has been an essential part of the fate of some of our writers . Most American storytellers, for better or worse, have to face William Faulkner (like poets, sooner or later, have to face Whitman). Gabriel García Márquez, who in turn has been gutted by Isabel Allende, Laura Restrepo and Toni Morrison, does it, always as the dutiful son. Sergio Pitol, and here is his originality, does so as a nephew. In any case, the barbaric notion of a book composed of other books does not seem to predict anything ungrateful; however, it corresponds to one of the most pernicious sequel of world literature: the anxiety of influence. This dilemma led Carlos Ramirez Hoffman also known in Chile as Carlos Weider- to a series of compensatory fantasies. One of them, explicitly suggested by Thomas de Quincey, but waived in the Decalogue of Raoul Delorme- is murder.

If not by the novel Estrella distante, by Roberto Bolaño, we might have forgotten the barbarian writers. But since this book is full of references to Delorme and that man with no other moral aesthetics, heteronimia and murder that Carlos Weider (aka Carlos Ramirez Hoffman, Alberto Ruiz-Tagle or Jules Defoe) was, it is hard to ignore the hypothesis of a relationship between the requirements of the barbarous deed and the demands of the crime; as if aesthetic experience were somehow in the fundamentals of murder.

I think unnecessary saying that this alleged affinity -illegitimately outstretched- is alien to La aficion a escribir, by Raoul Delorme. However, the Dictionary of French Authors (Paris, 2006), which cleverly includes Aimé Césaire (Martinique, 1913-2008) and Edouard Glissant (Martinique, 1928-2011), surprisingly “forgets” his name. In fifty years some curious literary critic perhaps “rediscover” him with a curiosity similar to mine and may write a short article about La aficion a escribir. Sad, but true. I dedicate this article to my ancestor Nara Araújo (1945-2009), who has left some memorable essay to Cuban literature on Raoul Delorme and his impossible literature.