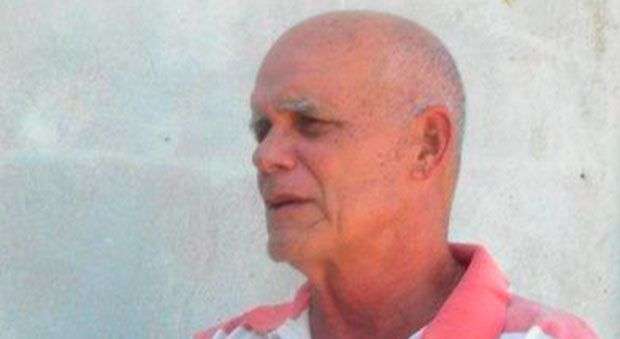

Pedro Juan Gutiérrez, authentic, visceral, corrosive, controversial and iconoclastic, is one of the most internationally read and edited Cuban writers. Although he was born in Matanzas in 1950, he spent most of his time living and working at the Havana’s municipality of Centro Habana. He, in his own way, honors and exalts it; he turned it into a character, beyond serving him as the stage for his stories.

Eschatology, sweat, alcohol, irony, filth, hunger, prostitution and of course sex with compassion, tenderness, passion, laughter, melody, delirium and hope copulate in his books. He defines himself as a normal writer, or the as the one trying to find what’s behind the darkness of each person. The truth is that his books are a reflection of his people, friends, and loves, longings from which he apparently feels harassed and tries to exorcise through phrases.

OnCuba went one afternoon to his terrace, planted on a roof in front of the Malecon with a marvelous view of the skyline and the Morro Castle, to see the sunset it had already seen in the pages of the renowned writer:

When you read Breakfast at Tiffany’s, by Truman Capote, at sixteen, you decided that one day you would write similarly. What was what seduced you the most back then from the world of literature?

A writer is first and foremost a great reader, this concept is fundamental and it happens to all of us who write. I read a lot since I was a child. I started with the comics of Superman, Donald Duck and Little Lulu , which were very cheap and there were tons of them. They were the biggest entertaining for kids of my generation. Those were another years and another life. From there I went to read newspapers, magazines and books, which are the different levels of reading. In Matanzas, where I was born, there are two large libraries where I could find everything. I was 16 when I became fascinated with Breakfast at Tiffany’s. I had already read several authors and this book seemed no literature to me, I thought it was written as a gossip, with extraordinary ease. I told myself that if I ever became a writer I wanted to write as well.

And what’s what most seduce you today?

Today I have published seventeen books, ten of prose and seven of poetry. I have said much of what I meant and I’m getting nearly silent . Lately I write very few, more poetry that works differently. I reread the classics, but virtually none new author. I also dislike rereading my own work; I do not care to go back. I’m at a point of writing poetry slowly, thoughtful and philosophical poetry.

What obsessions dominate you when facing the blank page?

The hardest thing is to understand what’s behind people’s action. Someone acts in a certain way but behind that person is what leads him to act that way and that’s what literature is. You must a lways try to go beyond the surface, to deepen further, which takes a lot of time. For example, I now started to write a novel about what happened to me in Mexico in 1990. 24 years ago I lived very beautiful, furious and terrible things. On that occasion I spent forty-five days there. I had six thousand dollars in my pocket and I thought at that time that was a lot of money. I went throughout Mexico; I went to Tijuana and then returned. That month and a half gave served me as a full year due to the experiences and the many people I met. It took me this long time to understand about what really happened at that time and I’m starting to write that novel that is flowing well, but I needed all that time to subconsciously write it.

What is your relationship with the tag of dirty realism endorsed to your work?

I have nothing of dirty, I’m just realistic. As you know this is a tag put but critics. It was created in the U.S. in the eighties to define a group of writers like Raymond Carver, Richard Ford, among others who were doing certain type of realism. This subsequently came to Spain and elsewhere and was endorsed to all those writing about things somewhat obscene. When the Spanish publishing house Anagram published Trilogy … they put it that tag, very commercial, which was repeated by journalists without deepening on it, perhaps for lack of time. I think there is not reality, neither dirty nor clean, just reality.

Then you are a chronicler of your time, as Carpentier would say.

I am a chronicler of my time and my space.

From your seventeen titles, the best known is Dirty Havana Trilogy, which has been published in more than twenty countries and translated into eighteen languages, what does this book mean to you?

It is a book with which I suffered a lot. I spent three years working on it and suffering it almost all the time drunk in this terrace. It was conceived in a very tough period of my life, of very sudden and violent changes. Like all my generation I devoted myself much to a political project that was falling apart. My marriage was being destroyed and I had to leave my children. Everything was sinking, my project of both social and personal life was falling apart and I, maybe not to commit suicide or be crying all day and be ashamed of myself, had to resort to alcohol, women, madness and despair. Others of my generation resorted to religion; others went to Miami. I have never liked to quit, I thought than escaping from Cuban reality at that time was an act of cowardice, I have that concept, but I also respect those who left because everyone does what he wants in a particular moment with his life. So I took that course and a bit as revenge I started writing these very tough and aggressive stories. I’m not repented by having written them but quite the contrary as they are part of my dearest work, my creation that I would save if I was forced to choose. Nowadays they are used in many universities especially in the U.S. and are used as a reference. It is among the books you must read before you die, the famous list that includes only four Cubans, each with a book: Alejo Carpentier, José Lezama Lima and Guillermo Cabrera Infante.

What other book would you save?

¨Rayuela, ¨by Julio Cortázar.

Virgilio Piñera in his story ¨Un Jesuita de la literatura¨ states that a writer is a man apart. Do you share this statement?

Virgilio was a man who suffered so much for everything. Yes, I agree that the writer is a man apart because he thinks too much and understands reality quite well.

What is your vision of Cuban contemporary literature, a day like today in which is held another International Book Fair?

There are two realities, on the one hand there are some writers with very interesting proposals , both inside and outside the island who are writing good things, but paradoxically their books are not in bookstores. For example, one or two thousand copies are made from Leonardo Padura´s work, which disappear in a sudden. On the other hand you get to a bookstore and find thousands of books that are to recycle and turn into toilet paper. It’s absurd the amount of volumes that nobody buys. In Cuba there is a good reading level, people read as much as in Mexico and Argentina, where there are a large number of readers. Our literary taste is made up by years of lots of literature and you find this extravagant reality on what is published which is quite complex and contradictory.

From the publication of five of his books in Cuba, do you consider that there is a kind of literary openness in the country?

I think so. There are now publishing officials who are younger, who have more open minds. When I published Trilogy … in October 1998, in Barcelona, and returned to Cuba in January 1999, I was expelled from Bohemia magazine where I used to work. I was fired with no explanation because they never told me what was that so bad that I did. Today that does not happen, a few days ago Zuleika Romay, president of the Cuban Book Institute, received me and we talked for over an hour in her office and she asked me, what has happened with you? Because she did not understand everything that happened with my work and censorship to which I was assigned. That gave me the tone for what is happening. There is also other political and social moment in the country, so I think we’re a little better about it.

Every literary work draws on the experiences of the author, to what extent do you consider yourself an intimate writer?

That happens to all writers, but not all admit it, maybe not get into troubles but I admit it quietly. I declare that I show in my books everything that happens to me, people I know, their situations and circumstances. You can not invent anything, the most you can do is adding a bit of sauce to disguise the situation, change something and change names.

How much does the Pedro Juan writer owes to the journalist you were for twenty six years?

Journalism has given me discipline to work. The writer can not live writing what he wants. He must get up early to be working when the muse to appear. Also research and observation, and taking notes come to me from journalism. The other thing that brought me is how to handle the language so that what I write not to become in a carnival of silly nonsense words.

What does living in Centro Habana, Havana, Cuba and write here looking to the sea at one side and a collapse to the other mean to you?

I’ve lived in Centro Habana for nearly thirty years. I have felt so confidant when anyone living at El Vedado or Miramar reads my books and then tells me she thought I was exaggerating reality but when passing through Cento Havana, she has seen these things and realizes that I am not exaggerating. I do not build anything; I have to reduce reality to make the context believable because its environment and circumstances are exaggerated in itself. It is also a risk because when people start reading your books you’ll get into trouble because they feel identified. You have to apologize or lie not to hurt feelings.

How did you feel when your first book was not published in Cuba and was also censored?

I submitted several of my story and poetry books to contests and never won anything. When I finished Trilogy …, which was not named that way yet, some representatives of Oriente Publishing House took it, read it and were so frightened that they did not respond, it was very rude. Then a friend traveled to Santiago de Cuba and picked it up for me. The book walked by itself, first by France thanks to a jury that came to Casa de las Americas Award and took it. Then it went to Spain and was published by random. One day I was called from Anagram publishing house and they told me they were going to publish it but I had to look for a title that would include all three of them, then I gave them this and they hung up the phone pleased. Once the volume was published I traveled to Spain to promote the book and when I came back I was expelled from journalism. In UNEAC (Spanish acronym for National Association of Cuban Writers and Artists) luckily I found great friends that did not drive me out and I was told to take it from the positive side, I now had more time to do my work. The next year ¨El Rey de la Habana ¨ saw light and so on. After five years seeing that I did not leave the country they began relaxing at me and published me ¨Melancolia de los leones, ¨a very innocent book. Then Letras Cubanas published me ¨Animal tropical¨ and subsequently ¨Nuestro GG en La Habana¨, ¨Rey de La Habana¨ and ¨Carne de perro¨and now I´m preparing ¨El insaciable hombre araña¨. ¨El rey de La Habana¨ had a small edition in America .

Wherever you publish a controversial book that delves into the conflicts of society there is immediately censorship because publishers get frightened. In Spain they say that it seems too much sex. I just got invited to a conference in Vigo, to speak of anything except sex. I was about to rudely reply to the lady who called due to such absurd. Of course I did not accept. I think censorship is implicit in humans, people are afraid of you to talk too much and complicate everything. As you know that has worked here in Cuba for many years.

My friend Enrique Pineda Barnet made ¨La bella del Alhambra¨ after the ICAIC (Spanish acronym for Cuban Film Institute) had rejected him three scripts. He has always been so censored like me. In my years as a journalist I spent so much time fighting with my directors. For example, you could not speak on suicide in the Cuban media, “We are heroic in Cuba and nobody commits suicide in Cuba”, it was me who first wrote about it in our press, which cost me over a year until I finally managed to materialize it. I found out that it was one of the ten leading causes of death in the country, it was the sixth in fact and therefore there was a national program for suicide prevention. Then I talked with the doctor in charge of the item at the Ministry of Public Health. Very happy he gave me all the information and did not know that the topic was taboo, it was forbidden, “Cubans are happy here.” I went to speak with the director of the magazine and told her we were going to do an educational article about how to prevent suicide, and through that approach it was how I managed to convince her. Rolando Pujol made very morbid photos that were never published, the work saw light with a more neutral snapshots. I managed to publish a deep article in Bohemia, with stats, which served as an example to several colleagues. That is very difficult for journalists, violating censorship. One of the main functions of journalists and writers is to put apart a little more each day what I call the border of silence, in all societies there is a border of silence and we have to move away a centimeter daily and increasingly speak of these dark areas. Readers appreciate it a lot because it helps them think and reflect.

How is the project of Spanish director Agusti Villaronga on filming your book El Rey de la Habana?

The script is already finished, excellent adaptation by Villaronga. Production and pre-filming are advancing. We already have the locations and the casting in which they chose very young actors, none known, was also done. It’s supposed shooting to start this summer, although producers are getting some permission yet. It pleases me a lot this book to be chosen for a movie, because it is a very endearing novel that took me a lot to conceive it.

Tell us about ¨Dialogo con mi sombra¨, on the writer job, your latest book.

All my books are posted on www.amazon.es. They have a page dedicated to me where you can buy them all; they send you by mail, even the online version; the latter just came out digitally. Union publishing house has it in its plan of publication, may be in a few years it will be around here, you know that these plans are delayed, but it is already on its plan, so we must be patient, but I am deeply grateful. It is a dialogue between Pedro Juan character and Pedro Juan writer, one goes asking and the other answers, I think it is very interesting and can please the public.

You have traveled half of the world where you are respected and appreciated by your work, why do you always return to Cuba?

Simply because despite everything I’m very happy here.