Revisiting her origins actually does not reveal data that is very different from those of other African-American singers. Born in 1939 in the Deep South as Ana Mae Bullock, who would become known to the world as Tina Turner, she went through the typical tribulations for those of her skin color and social background. She first worked picking cotton on a southern plantation, where singing has been a brother to sweat since time immemorial. Later, as a maid of a wealthy home, until she became a nursing assistant in a clinic in St. Louis, Missouri, when the civil rights movement was already deeply permeating U.S. society and culture.

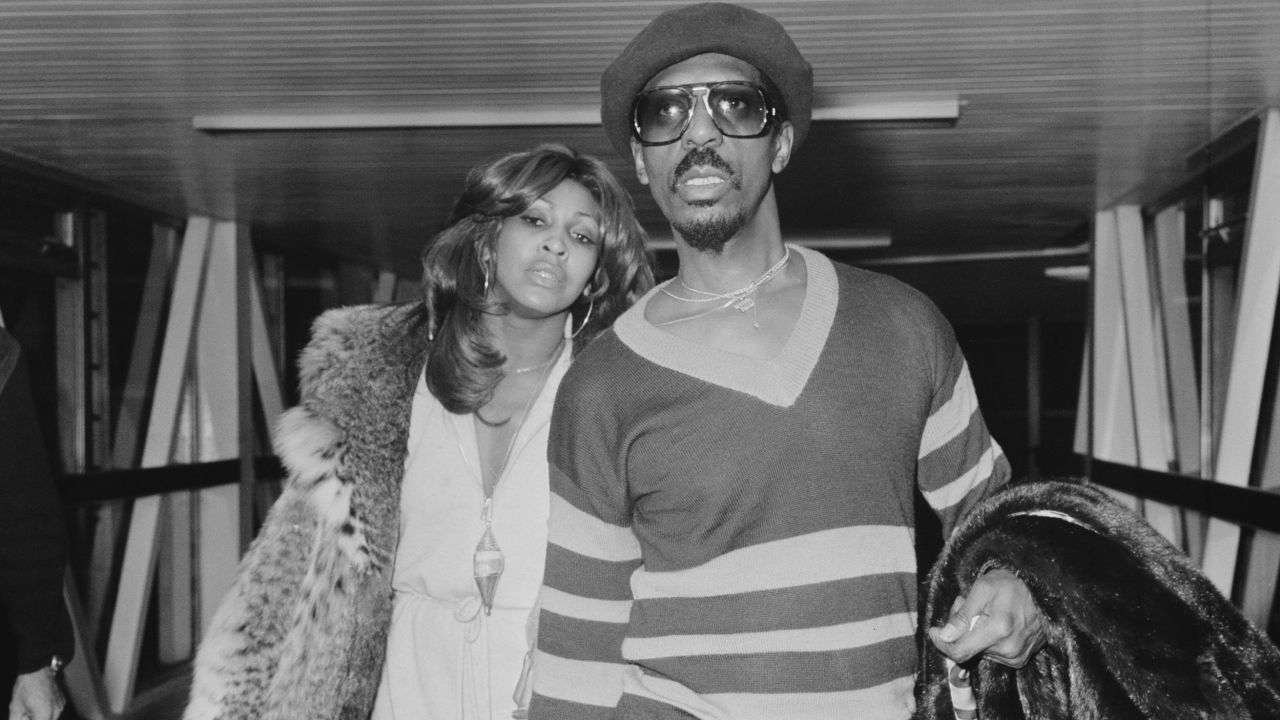

While there, she worked until the night she met Izear Luster Turner (1931-2007), better known in the world of music as Ike Turner, in a nightclub.

When he saw her sing, the director incorporated her into his band, Kings of Rhythm, and introduced the secrets of R&B to a 16-year-old girl who until then had only sung, like other black divas, in the town’s Baptist church. She also gave a sense of movement on stage, in which explosiveness and sensuality were two sides of the same coin, the same one that Tina would later pass on as inheritance to a young British rocker named Mick Jagger.

Turner made her recording debut with the tune “Boxtop,” composed by Ike and released on Tune Town Records in 1958. Two years later “A Fool in Love,” written by the same author and sung by her, became a national hit that sold a million copies. After the turning point, both artists began to present themselves under a new name: Ike & Tina Turner Revue. And with a group of backing singers, they called “the Ikettes.”

In 1970 they released their version of “Come Together,” by Lennon and McCartney, which gave them more national relevance, along with their way of interpreting “I Want to Take You Higher,” by Sly and the Family Stone. It’s because of things like these that the Ike & Tina Turner Revue became, critics said, “one of the hottest, longest-running, and potentially most explosive R&B outfits” in the United States. In 1974 they released The Gospel According to Ike & Tina, nominated for Best Soul-Gospel Performance.

The same year came her first LP Tina Turns the Country On! which earned her a nomination for Best Female R&B Vocal Performance. That same year, Tina went to London to appear in the rock opera Tommy, to music by The Who, in a performance that was acclaimed by both audiences and critics. The inspiration for her second solo foray: Acid Queen (1975) would come from here.

But Ike was a cocaine addict who involved her in a relationship marked by psychological abuse and physical abuse, which would end in a divorce after more than fifteen years together.

“I was living a life of death,” Tina said in an interview. “I didn’t exist. I didn’t fear he would kill me when I left because I was already dead. When I got out, I didn’t look back.”

By telling her story, Tina made an important contribution to an entire generation of women who would be full of courage and come out to expose cases of abuse in an environment where violence has been “our daily bread.” Above all, she helped to break stereotypes: definitely, this form of violence was not an exclusive “heritage” of poverty.

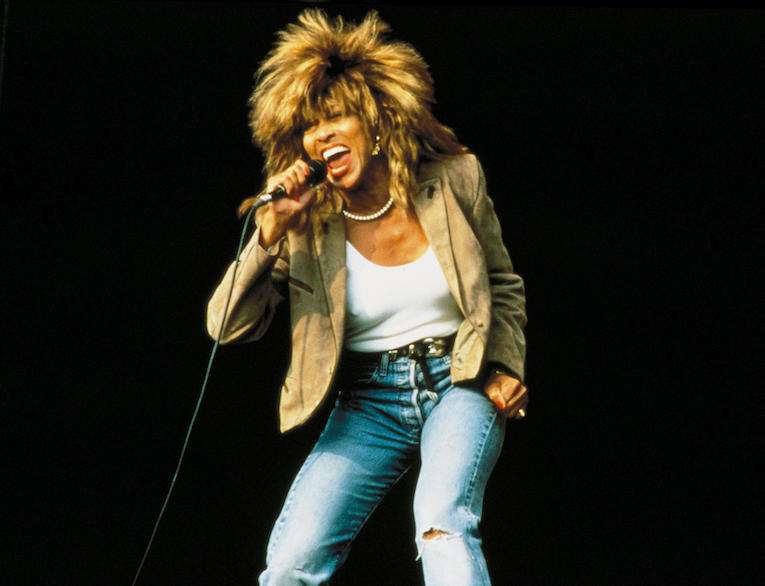

After the divorce, in 1978 she released her third solo album, Rough, followed by Love Explosion, which included a brief foray into disco. They would not be critics’ or public successes. But her presence alongside rock stars like Rod Stewart, with whom she sang a famous tune alluding to her legs (“Hot Legs”), “the most famous in show business,” and Mick Jagger during the Stones’ U.S. tour in 1981, would help pave the avenue for her next leap in the 1980s, in which she would project herself as a global rock superstar, capable of filling stadiums with people speaking different languages and moving crowds to see that marvelous woman sing and move on stage as if she were one of the seven Greek muses. It is precisely what Private Dancer (1984) marked. “I don’t consider it a comeback,” said the artist. “Tina had never arrived.”

Her version of “Proud Mary,” the John Forgerty tune released by Credence Clearwater Revival, the same one she had been singing since her days with Ike, managed to penetrate deeply as an identity mark in U.S. culture when sung by heart by several generations, a fact comparable only to what happened with Neil Diamond’s “Sweet Caroline,” a sort of second national anthem.

Her final years were marked by illnesses and personal misfortunes. She had intestinal cancer in 2016. A year later she had to undergo a kidney transplant, donated by her husband, the German Erwin Bach, whom she married in July 2013 after twenty-seven years of relationship and living together in Switzerland. And she forgave Ike, who had made her life unlivable.

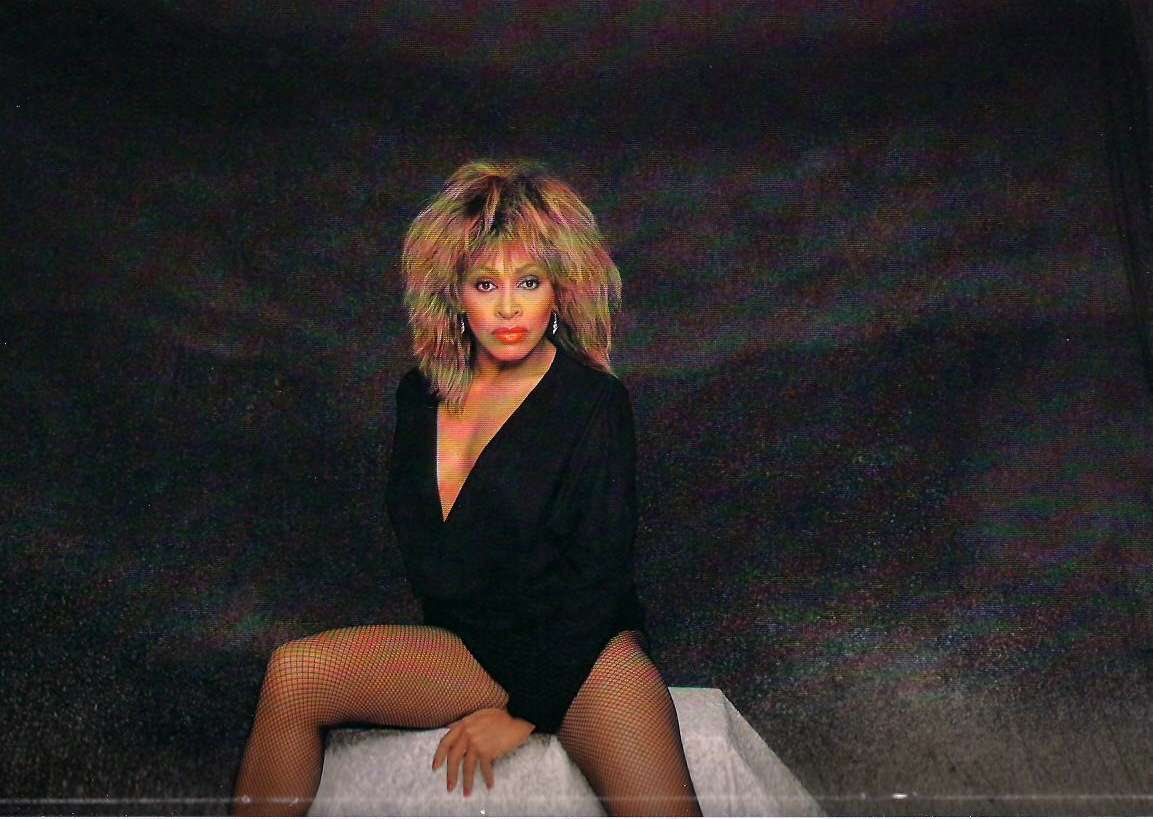

Among many other accolades, she has garnered 12 Grammy Awards. She is the only woman to have won a Grammy in pop, rock, and R&B. “River Deep – Mountain High” (1999), “Proud Mary” (2003) and “What’s Love Got to Do with It” (2012) are in their own right in the Grammy Hall of Fame.

A rock star, simply the best.