Diago works in an inviolably systematic way, and always has “work done” because his goal is to enrich his project, and he is not restrained to a single specific idea or presentation. “For me, art or creation is freedom; sometimes the work that I am building changes whatever concept that I might have had in mind until then. Your day to day work guides you in what color is required, what kind of material, and that changes the whole concept, and therefore, its presentation,” he says.

His first solo exhibition was in 1994, in Olorón, “a small French town, very little, pretty, very close to the Pyrenees. With that exhibition I broke the ice, and I marveled at seeing that the public understood what I was proposing and found it interesting. For a beginner, that is encouraging, because it is a way of losing fear when the time comes to show your work. When you’re a recent graduate you have a lot of doubts, and as the years go by, you feel like you are creating one big thesis everywhere you exhibit. You have to design interesting projects like that whether they’re for Havana, Paris, New York, Madrid or Burundi.”

Graffiti is recurrent and words—interweaving popular speech with elements of high culture—have appeared from the beginning, “more because of my friends than me,” he admits, “because they help spectators to be introduced to the work,” contaminating it. “For those who do not have all of the intellectual tools, understanding the message can be difficult, hence words as an orienting element, but without forcing the work; that’s something I never do.”

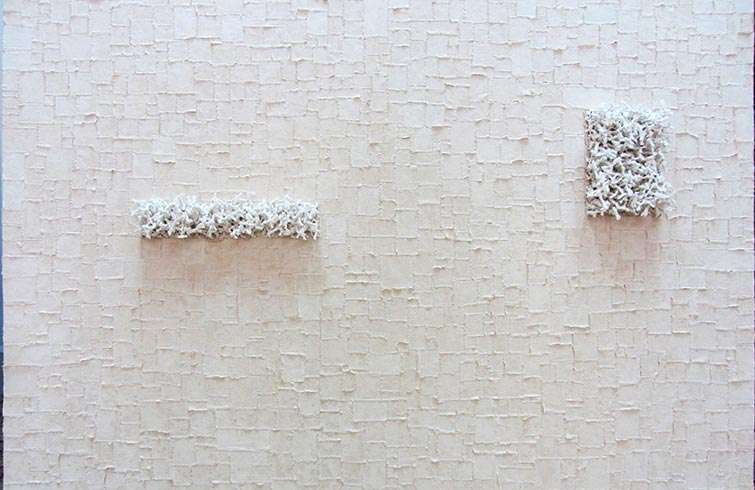

Diago’s palette—quite constrained and sober—is another one of his characteristics and is very much related to his beginnings in the complex 1990s, when Cuba was going through an acute economic crisis. “At school we had everything, and then suddenly, the supplies were all gone, but we had to work. That was when I began using tar, cement, or whatever I could find, and that type of material only allowed for the use of ocher and sepia tones. I carried out exhaustive research and connected with matterist art and the arte povera tendency, which emerged in industrialized societies where they have everything but went for the simplest elements, the basics. Creating my own aesthetic out of precariousness has given me excellent results and satisfaction.” For the last 22 years, that has been the premise of Diago’s work, and while he stresses that he is “open to other materials,” he does not like brusque changes, nor will he make any concessions to the market. “There are aspects where I make no compromise; I do what I feel, how I feel. Period.”

Another unique aspect of this artist is that he comes from a very unusual family: on one side, his grandfather Roberto Diago Querol is considered as one of the first artists to understand and assimilate abstraction; on the other, the Urfé family, which has produced renowned musicians. “But the most important gardener was my grandmother Josefina. Every Saturday she would pull me out of the baseball game and lead me by the hand to the National Museum of Fine Arts to take painting classes with Mercedes Peñaranda and Oscar Morriña. My mom wanted me to go into a military career, but my granny opposed it. I will always be grateful to her!”

Large format seems to be comfortable for Diago because “it makes it easier to catch the public’s attention, and it is as if the work were shouting ‘Look at me!’ A large size allows me to overwhelm the spectator,” to be revealing without false modesty. At the same time, he emphasizes that religiosity in Cuba is “an everyday thing. It has been a weapon of resistance throughout all the ages. It comes from our ancestors and endures. Religiosity is incorporated into everything that is Cuban, one way or another. It is part of us.”

Memory also permanently pulsates in the work of Diago, who has touched on elements that border on what could be described as marginal, but he is not afraid of the term. “The elite marginalize you…they put you ‘outside of,’ and you begin to question certain postulates; I felt the need to give a voice to my friends from the humble Pogolotti neighborhood; they are the protagonists in a number of my works.” He does not go to the mountain but to intellectual terrain, because “thanks to high culture, you refine the blow, but the blow is twice as weighty.”

Could Diago be a 21st century cimarrón?

Juan Roberto Diago Durruthy

(Havana, 1971). Graduated in 1990 from the San Alejandro Art Academy with a specialty in sculpture. His work can be found in dissimilar and well-known collections, such as Havana’s National Museum of Fine Art (Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes); in Paris, France (Guislain Etats d’Art gallery; Kikoïne Foundation; Brownstone Foundation); in Panama (Coral Capital Art Collection); in Beijing, China (District 798, Xin Dong Cheng Space for Contemporary Art); in Germany (Rubin Museum of Art: The Collection / Hans Georg Nader Collection, Duderstadt), and in the United States (Cernuda Arte, Miami; Pan American Art Gallery, Texas; Fort Lauderdale Museum, Florida; CIFO Collection, Florida; Stephen Cohen Gallery, New York; Museo 54, New York; Pizzutti Collection, Ohio), and many more.

He has won major prizes and awards, including the National Culture Distinction (2002); the Prix Amédée Maratier (1999); Remis par la Fondation Kikoïne sous l’ égide de la Fondation du Judaïsme Français (awarded for the first time to a Latin American artist); and the Raúl Martínez Special Award (granted by the Hermanos Saíz Association (1995).