“It’s not a professional recording, but one can hear the drums here [and the sound reverberates]. And an almendrón that goes by every two seconds or the seller of ice cream or avocados. Wow!” He sighs, but without feeling fed up, as Cubans do when they extract the humor from adversity, and looking towards the roof of the room, he smiles, while by Aramburu Street, magically, what goes by is silence to refute his little agony.

Only three types of people would dare to build a recording studio in a house with a street door, without noise trap and in the middle of the endemic hustle and bustle of Centro Habana: the ignorant, the crazy and the optimists.

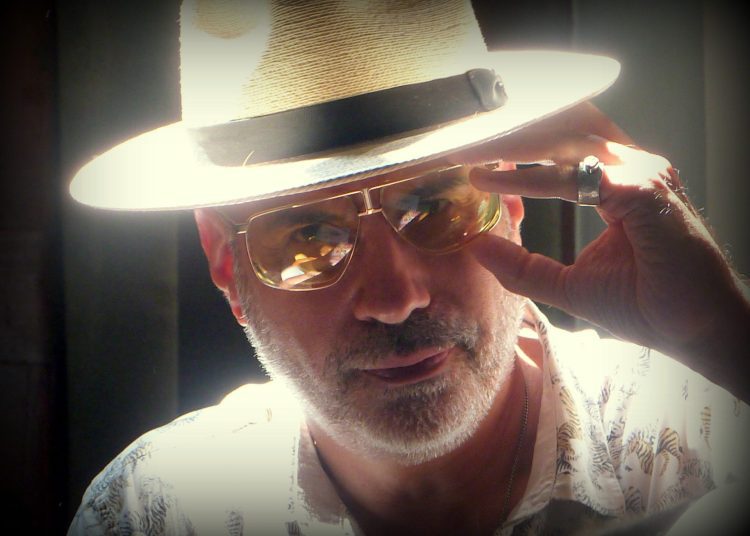

Andrés Levín (Caracas, 1968) is not in the first two; although, psychoanalyzed, he would not be a stranger among the second. Leaving aside the permutations of suspicion, we are definitely facing a man full of optimism that devotes himself to projects in Cuba that in prudent spirits would be politely declined. The cause? They demand a being very audacious.

TEDx to give Cuba 2.0 an impulse

Like every intelligent man with initiative, Levin’s things happen. So, a New York morning in 2010 he woke up under the empire of a question: “How do I do something with all these incredible people I have met?”

On his trips to the island, which began in 1998 as a producer of Sony Music to make an album in the old Egrem recoding company with Cuban classics sung in French by a Frenchman, Andrés Levín dedicated himself to nosing around Cuban society. He didn’t know much. In the 1980s his connection with the Caribbean socialist bastion was music. Vinyl discs, among many others by Cachao López, one of his favorites. His inquiries were from top to bottom and vice versa. With gregariousness, tact, simplicity and, of course, much curiosity.

That’s how he met personalities of religious culture and syncretism, such as Natalia Bolívar, or the plastic artist Stereo Segura, acquired by the MoMA or an habitue of the Venice Biennial; but also people from the street, unknown rumberos, neighborhood musicians, undeserved entrepreneurs without fortune, speculators, shady businessmen. Then, during the first Obama government, another question asked himself, she loves me, she loves me not: “Will they let me; will they let me not?” After all, TED, which means technology, entertainment and design, for its English acronym, is a non-profit platform designed almost forty years ago by Richard Saul Wurman with Harry Marks and has landed in about 170 countries.

“I told myself: it will be impossible…but I did it,” Levín says, remembering, satisfied, the two TED talks at the National Theater of Havana — InCUBAndo (2014) and Futurisla (2015) — for which he had to get money from U.S. Foundations and persuade both the State Department and the Ministry of Culture that “everything was within what was allowed and favored the agenda of the two governments; and to me it seemed fantastic to be part of them. Obviously, there were recommendations of…don’t include anyone who has any political angle in the talk.”

As an advance of what is the artificial intelligence boom, in Futurisla many were speechless to see and listen to Bina 48, at the time one of the robots with the greatest capacity for socialization in the world, composed of information from numerous people. For the occasion it was programmed in Spanish and therefore could interact freely with the Cuban auditorium, about 3,000, mostly young, who crowded even in the hallways of the Avellaneda room to savor a slice of the future.

Peace concert, Pichi and a definitive love

In 2007 Andrés Levín had finished co-producing the album Papito, a successful double album of duets by Miguel Bosé. Upon leaving the recording studio, the Spanish singer-songwriter told him about the preparations for an edition in Havana of the Peace Concert, a Colombian initiative to help peace efforts with guerrillas and other armed groups. Two years later, Levin landed in the Cuban capital with the singer Cucú Diamantes, then his romantic partner, two backup singers and Bosé’s band.

Still with the hangover of the more than a million Cubans gathered in the Plaza de la Revolución wearing white clothes and chanting songs (never again has such a crowd, typical in the first decades of Fidel Castro, gathered in the historic place), Levin sealed his commitment to the island.

“That same night I met Pichi [Jorge Perugorría] and we decided to make a film [Amor crónico, 2012, with Cucú and the producer himself in the cast] and from then on my interest in Cuba has multiplied, always creating more and more links and projects to bring here.”

Tribe Caribe

What value does Cuba have that justifies that energy towards us?

Look, it’s a good question. First, I always felt like family here, which I didn’t have in New York. At first I lived in Bahia, which I love, but it was very far from the people I have met, the projects, the music and here, in Cayo Hueso, a few steps from Trillo Park, I can make a difference in the community, in the culture, in the lives of the people, not only those who are here, but those who come from there [foreigners] to here.

You commit to social transformation, at least at the community level….

I took it as one of my missions to do a kind of micro and macro social change project. Micro in the sense of my friends who come here from there and who are artists who spend 72 hours in Havana, go back changed and leave something behind; and the projects that I have been able to do here, like TED, and the most complex and ambitious of all, Tribe Caribe, which is our content platform, both for music, art, but it is also a hostel and in a certain way it is this recording study and the intention is to create a Caribbean voice. Throughout my career I have been very interested in the fusion of Afro-Caribbean music, and how to increase the little artistic communication between Cuba and Jamaica, Haiti, Colombia, Puerto Rico.

And Tribe Caribe is a facilitator of your ambitions….

Tribe Caribe is a base of exploration and inter-Caribbean collaboration. It is like the Caribbean tribe, it is a play on words, the R, the I, the B, the E, are in both words, but beyond the lexical sense, it is to affirm that we are a tribe that has much more in common than not in common. It is unraveling the knot of why there is not more interaction in the Caribbean, because it seems to me that together we are going to make a great voice for global culture.

Andrés Lavín, who in 2016 brought the queen of Spanish pop, Martha Sánchez, to Havana to sing at the Week against Homophobia and Transphobia, is producing an album with songs that each fuse at least a couple of Caribbean cultures. The Cuban band Osain del Monte is involved in the project, which is in charge of reviving genres such as yambú, guaguancó, columbia, as well as songs and toques belonging to Afro-Cuban religions.

With no less Caribbean will, another of the initiatives took place during the opening of an exhibition by the photographer Juan Carlos Alom, (Havana, 1964), whose photographic series Nacidos para ser libres has been acquired by the prestigious collection of the British National Museum of Modern Art.

One Saturday afternoon, Levin cajoled the Cayo Hueso community with an unprecedented sound: contemporary music from Jamaica. He brought in, for the purpose, a DJ from Kingston to “see what happens.” The result? “It was incredible”. He remembers that at first the old ladies and kids in the neighborhood wondered what genre was coming out of the speakers. It was not reggaeton, it was not salsa, nor cubaton, nor timba; much less singer-songwriter music. So? “Here the range of musical styles is wide, but specifically what is playing in Jamaica is not heard. However, after an hour and a half everyone was enjoying themselves and partying, as if we were in Kingston!”

How was the sustainability of the project conceived?

I work outside of Cuba so I can do things here. In the case of the jazz festival, they lend us Trillo Park, the lights, no tickets are sold, there is no label behind my albums, everything is totally independent. Obviously, all musicians get paid, but if there is no money, there is no money, and they play the same. There is much more artistic flexibility than in any other city in the world that I know.

What does your work abroad consist of?

I work in publicity in Mexico or the United States. With a commercial I can pay for a couple of songs, for example.

Do you like making them?

Yes, I like them. I don’t do many so as not to become a toothpaste factory, but luckily they call me for more cultural projects and I love them. For example, last year I did a cover for the song “Gracias a la vida,” by Violeta Parra, for the Tequila Patrón campaign. I did it with American soul singers, with my arrangement completely a cappella in English. It wasn’t just a jingle.

Another thing I did was the latest campaign for Mexican beer Victoria — which, like tequila, I love — and then we brought the entire team to do post-production here. Jon Batiste, for example, wants to come and record here. I think that this humble studio can be used for music from everywhere. Cucurucho Valdés, Yaroldy Abreu, Alejandro Falcón and Oliver Valdés, among others, have already passed through here.

Vintage, oil paintings, yoga and a rooftop Havana landscape

In the project’s sustainability equation there’s a luxury variable: the Tribe Caribe Cayo Hueso hostel. Conceived as a boutique hotel, the eclectic five-story building built in 1930 features eleven intimate rooms and suites, private balconies, vaulted ceilings, original classical tiles, chandeliers and a cage elevator. Each room is decorated with locally sourced period pieces and original contemporary artwork by Cuban and Pan-Caribbean artists. The bar, on the roof, allows you to dominate the old and modern areas of the city, with its gray tones, its flocks of pigeons and its twilights at the foot of the Gulf. When you wake up, a yoga service can restore lost balance if it was a rough night. Only the oldest remember that the Neptuno bar was there, which ended up being a seedy refuge for the many broken hearts of all time.

At the community level, is there a spillover of these profits to the residents, for example, or is the neighborhood simply part of the decoration and the hostel is a kind of pearl in the swamp?

In the sense that there are thirty or forty people employed on the project, there are tangible benefits. I’m not the only partner, luckily. This is not a foundation, but it works as a kind of mentoring, so that people learn to do sustainable projects, and that requires a lot of attention to expenses, the punctuality of inputs, changing with the times and their difficulties, because enough people are not coming, or there’s no gas, or eggs for breakfast, then you have to do something else.

The important thing is to continue generating projects for the people of the neighborhood and that they continue to be free. I don’t see a time when we’re going to sell tickets at Trillo Park. The day of Van Van’s concert it was obviously free and 2,000 people came, people who had never seen Van Van in their neighborhood. The cost of that, compared to the result, gives you the value of the contribution, which is the opportunity to do more with less.

“Manteca 2.0”

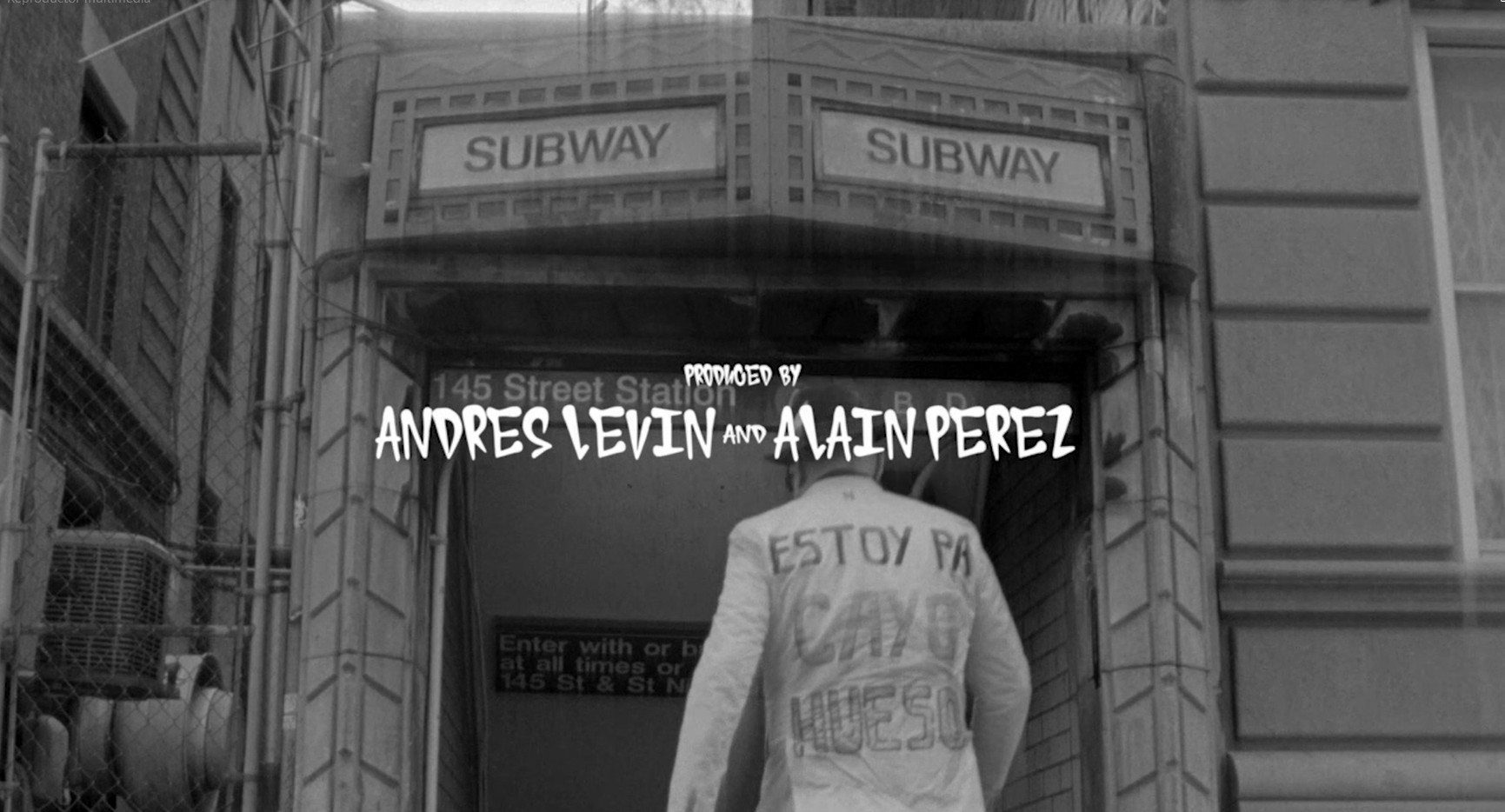

Memory, sensuality, history, identity, joy, legacy, vitalism, updating of the myth converge in “Manteca 2.0,” a resounding video directed by Amén Perugorría, filmed in black and white, with arrangements and lyrics by Alain Pérez — “one of the best and most impressive musicians in the world” —, Gradelio Pérez and Andrés Levín himself.

“The song is a tribute to this neighborhood, to its values, through one of its sons, Chano Pozo, whose vital journey from Cayo Hueso to New York, where he meets Dizzy Gillespie and together they compose “Manteca,” in 1947, changed jazz and its history forever when Afro-Cuban percussion entered.

Bringing back to Cayo Hueso the musical powerhouse that is Luciano Chano Pozo González, who was shot six times in Río Bar Grill, located on the corner of 111th and Lennox streets, in Harlem, in 1948, also extends the exercise of memory and recovery of the legacies left by other luminaries of the community: Juan Formell, Omara Portuondo, Moraima Secada, Félix Chappottin, Carlos del Puerto, Los Zafiros, the historian Eusebio Leal and Pedrito Martínez, who grew up here and whose family still lives in the neighborhood.

Filmed in an eight-block square, “Manteca 2.0” has the added bonus of authenticity: a mirror in which about forty people from Cayo Hueso look and recognize themselves. The watchmaker, the boys who box or play soccer (there is never a baseball scene), the pigeon breeders, those who work in the rubble of the constructions or reconstructions of the community, the street vendors, the drinkers of rum and other aromatic herbs, the pedicab drivers, the tai chi practitioners, and motley neighbors, whose glances towards the camera lens document their own — and often precarious — existence. And, in the middle of the parade, we discover a smiling Andrés Levín who takes off his welder’s mask in a metaphor of an acquiescent filler of wills.

“Cayo Hueso as the cultural and musical epicenter of Havana and Cuba is a topic that interests me a lot,” insists Levín, whose video “Manteca 2.0,” which features Los Van Van, Alain Pérez, Pedrito Martínez, Yissy García, Gonzalo Rubalcaba, Rashawn Ross and Ron Blake, will be launched on international platforms this September 15, being accompanied at the Tribe Caribe hostel’s Manteca Bar with two drinks of ingredients under absolute secrecy: Dizzy and Chano.

Conversation on the celebrities’ couch

You have a Jewish surname and were born in Caracas. Something bizarre behind it?

The short version is that my Argentine parents were political exiles in Caracas in the late 1960s and I was born there. My Jewish ancestry comes from Germany, I have a German passport. In 1937 my Jewish exiled grandparents fled from Berlin, via London, to Buenos Aires. I am really German, Argentine, Venezuelan, American, wanting to be Cuban.

Chaotic….

Exactly. Of all the passports, the one that really works is the German one.

If said by a Jew, it’s something…curiously ironic.

Yes, I went to the German embassy in Caracas saying that although my parents are not German, but Argentine, I had to skip a generation and I told them: “If it weren’t for Hitler, I would be a Berlin boy, so look at me here in Venezuela, I have to get something in exchange, right?”

Were your parents left-wing militants?

They were left-wing students, Argentinian, hippies, not very religious, so I was not raised in the Jewish rite. My grandparents were traditional.

Don’t you have a menorah or kippah here for when you go out?

No. But I have used it when I have worked in the film and music industry. My friends from those sectors are all Jewish, so after I became a professional I started to practice more, but more for social reasons; although I have the soul of a Jew. However, I’m not a very good businessman.

Are you a jeweler or do you know about jewelry? Are you perhaps a mathematician, so as not to leave out any clichés?

Well, I’m a musician and I make a living from it. I also have a super dry sense of humor.

Woody Allen style?

A la Woody Allen. That’s a joke, as they say.

In your biographical profile it is stated that you are a philanthropist. Do you deserve it or is it exaggerated?

In principle, I have fifteen or twenty social projects that I have done with foundations, but I’m not a millionaire who is donating the remains of his Jewish family’s fortune to Cuban culture. (Laughter)

I read that you studied at the Berklee and Juilliard academies. Are they as reputable as they say they are?

Obviously not, because they let me in.…

You don’t lose your humor….

Hardly ever. When I was at Berklee, the good thing was that it gave you the opportunity to work very hard, and you had the tools, but there were also kids who only went to study to learn how to make rock music arrangements, and on the other side was Keith Jarrett and other great jazz players. Juilliard is much stricter, and obviously focused on classical music, unlike Berklee; but they gave me a full scholarship there, they paid for everything. I never knew if it was my talent or because they had to have a quota from a Latin American and I was there.

Do your musical beginnings go back to childhood?

Yes. My father made experimental music, and when I was 7 or 8 years old I have photos in which I’m with headphones doing sound effects and sound art basically and then I got into rock and roll, I played in fifty kids’ bands and since there was a studio at home I made recordings playing all the instruments, and that’s what I sent to Berklee, which is why they invite me to study there. After a year I left.

Why?

Because I discovered New York. There I began to study at Juilliard and do part time in studios. I applied to thirty-five and only two admitted me. I happened to fall into one where Lou Reed, Laurie Anderson worked, and in the other room, Nile Rodgers. I was very good at programming synthesizers. So instead of making coffee and cleaning toilets for three years, which is what kids do, three or four weeks later I was in the studio programming a system worth a million dollars, which was owned by Stevie Wonders, Rodgers himself, who was my mentor, and Trevor Charles Horn. There were about four or five in the world, because they were very expensive and complicated, and I knew how to use them. That was a steppingstone to being able to be in the studio at 18 with Diana Ross, Chic, The Vaughan Brothers.

In the first four or five months I was involved in records of that stature as a programmer and in some cases composing. I worked 20 hours a day. I had no life, I had no girlfriend, I had nothing, no friends, nothing. The other studio was at 47th Avenue and Broadway. Hip hop was recorded and the singers all carried guns.

All of that was like in two or three years and then Misha, an English soul singer, calls me when she hears a couple of my demos. I did her second record, and that put me on the map as a music producer in the world of soul and rhythm and blues. The album was very eclectic and very interesting, and when it came out Chaka Khan, Tina Turner, Gladys Knight called me, they sat down to talk to me on this sofa where we are now, and then I did a lot of rhythm and blues, and I started to delve into Brazilian music. I had a hit before with Martha Sánchez and Olé Olé. The song was called “Soldados del amor.” I ended up moving to Brazil for several years, and that’s when I worked with Caetano Veloso, Carlinhos Brown, Marisa Monte, Arto Lindsay, Brazilian-American composer and guitarist from the New York underground and avant-garde scene. Then I went to Nigeria to do a Fela Kuti tribute, and in the middle of all that, I did half a David Byrne record.

You also have a history with Latin American rock….

I made the first iconic rock records in Spanish by the bands El Gran Silencio, Aterciopelados and Los amigos invisibles. I also worked with La Portuaria, I made two albums with them, but there were more Caribbean ones.

And Yerbabuena, when does it appear in your creative life?

In the middle of all that maelstrom. We worked for almost ten years. Records, tours. Yerbabuena was the musical mix of everything: Africa with jazz, R&B, cumbia, the fusion of all those things that I loved, and in live that band was a train, fourteen musicians on stage.

The fact that you chose Cuba is not pure whim. What values do you detect in Cuban society, even in the midst of this unresolved crisis that we are suffering? Do you think culture saves and saves us?

A very difficult question to answer. It’s like…what we are left with is culture. I am also seeing the great exodus of people from here. Obviously with the possibility of coming and going, but I do feel that there is a new generation that I didn’t know about and that they are excellent creators. In other words, I am also very optimistic in general, I have people who tell me: “But you love everyone.” I do not live without knowing the reality, not the obvious; but I always try to help most of the time and the projects have that community part, I think what I can do is get more resources to do more projects here. That’s the part I do. Yes, in that sense culture can save. There are very interesting projects that will change people’s lives both here and there. I see my role as a kind of bridge and that’s what I’ve been doing for a bunch of years. Did I answer your question?

In one of the many incursions that Dizzy Gillespie made to Havana, starting in 1977, he visited the neighborhood of Cayo Hueso and asked where a statue or a bust or a plaque of Chano Pozo was, although in fact Pozo was born in La Timba, a Havana neighborhood adjacent to the Colón Cemetery, where the percussionist is buried. Among your plans would be to settle that debt of others?

It would be a good project. The idea is to make a giant graffiti on the facade of a building in Cayo Hueso with the image of Chano and Juan Formell. The problem with those things is that you put one and exclude the others. People who have been here for less than thirty years don’t know who Chano Pozo was, but I think that with three concerts we can change that.

And do you think that at the level of jazz, this new generation of Cubans is contributing as much as the pioneers did in the 1930s and 1940s in the United States? Machito, Bauzá, Camero and many others….

I would say yes, although they are different. Any American, Senegalese, Brazilian percussionist who sees Pedrito Martínez play is going to say “waooo,” the same with Dafnis Prieto, with Horacio el Negro, or with Gonzalo [Rubalcaba]. They all have a uniqueness — not only in talent, but in vision — that makes them unique. But jazz is in great danger of being repetitive, and I think that jazz in Havana needs an injection of concepts. It has an impressive level of musical virtuosity, but original ideas do not flourish every two weeks. I think that not having the Internet for so many years maybe limited a bit access to what alternative music is. In New York or Bahia, Brazil, there is much more experimentation that generates ideas and many more possibilities of places to play. Here making a living from music is practically impossible, unless you travel.

And on a more elitist level, if the term fits, have you found here the possibility of making a more technically elaborate music project?

Here, elitist, yes, no problem. Look at me, Jewish, German, Juilliard, I have a Chinese dog, I don’t even make its food; I have a private boxing coach, he is a friend of mine and thanks to him I recovered the wallet that was stolen from me a couple of days ago in the agricultural market due to carelessness. It was hilarious, because they wanted a reward for handing over the wallet and he told them: “I’ll work with him and tell the person who stole the wallet that the reward is me.” And the next day he already had the wallet, without the money, of course. Here everyone is multipurpose. Even me.

And the work with the batá drums?

I’m again cooking something with the batá drums. And I have made several pieces at the Havana Biennials with batá drums. I did a piece called “Abatar,” interactive with thirty batá drums in the street, and then in Fábrica de Arte a choreography with Claudia Hilda, I wrote like a suite for nine batá drums, but totally twelve-tone, contemporary.

Like Schoenberg.

Yes, more or less. I love the sound of the batá.

It strikes me that you can connect with neighborhood music and with, let’s say, sophisticated music, without blushing. The music is one.

As a child I was exposed to experimental music, which is the best thing that can happen to you because if you start with noise, what you learn, in one way or another, is an organized variation of that noise. So I love electronic music, classical music, improvised music, jazz, and I think that unlike my contemporaries (this is the longest interview of my career), who became great rock producers, great jazz producers, they only make music for movies, or advertising, I am always changing my style and working a lot on different musical universes at the same time and that is what I look for and it keeps me more alert. When my father invited me to play the guitar, a blues, for example, he scolded me if I imitated Hendrix. He forced me to detune the guitar and look for something strange in the sound. I always had that school of experimentation and if I had children and they were musicians I would be just like my father.

What prevents you from resting on your laurels?

Curiosity. I think.

You’re lucky you’re not a cat.

Coda

Some of his many friends in the United States have seen Andrés Levin as a salmon swimming against the current to spawn in Havana. Knowing a few things about here and ignoring many others, their common phrase was: “What the fuck, man?”