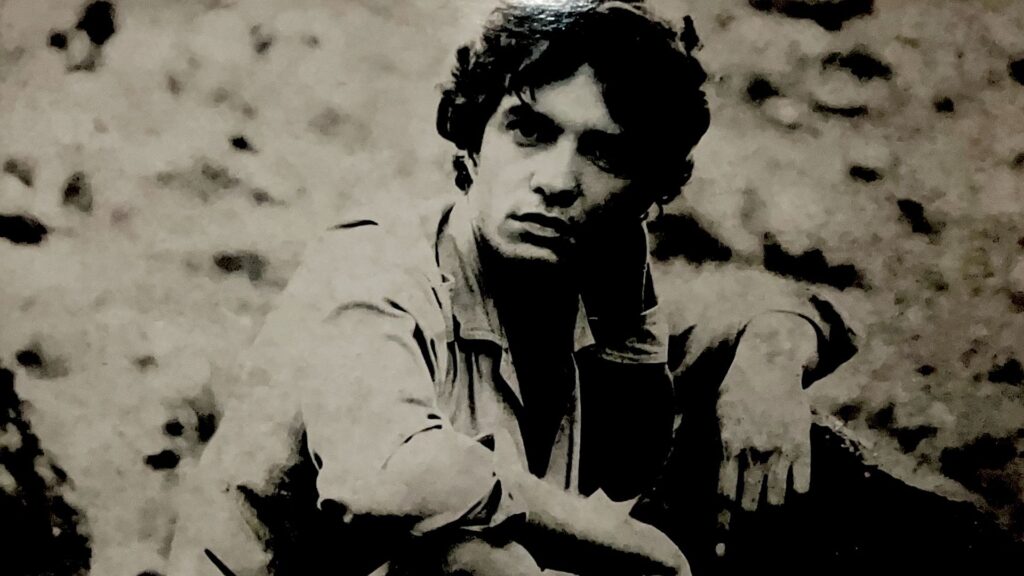

Fernando Hechavarría (Santiago de Cuba, 1953) is a solid reference on the Cuban scene since the mid-1970s, when he joined the Teatro Escambray, a flagship group among those who embraced the method of collective creation as an aesthetic and life practice. Since then, almost fifty years of success mark the career of this versatile actor, who has had brilliant performances on stage as well as in film and television. Today he is one of the best-known faces of Cuban culture. Since 1995 he has belonged to the cast of El Público, a group directed by Carlos Díaz, at the forefront of the country’s performing arts avant-garde.

Fernando has a degree in acting from the Faculty of Theater Art of the Higher Institute of Art of Havana, and a master’s degree in Training Processes of Artistic Education from the same educational center. In addition, he has received professional training and workshops in his specialty with such relevant personalities as Santiago García, Eugenio Barba and Leonid Velejov. For twenty years he has been teaching acting at the ISA, University of the Arts.

This is what we asked him. This is what he told us.

You studied plastic arts in Holguín in 1970. How was the transition from aspiring painter to aspiring actor?

I was born in Santiago de Cuba, and moved to Holguín, where I studied Plastic Arts from 1970 to 1972. There I had an excellent design teacher, Paneca, who suggested I enter the world of acting; my reaction was: “Am I that bad at plastic arts?” He replied: “No, but there is potential as an actor that you don’t know about, and that you should explore.”

He asked another teacher, a friend of his, who was part of the theater faculty at the National School of Art (ENA), to fly to Holguín; he examined me, I passed and the following summer I was in Havana, studying acting.

Thus, without prior expectations, I discovered and fell in love with theater.

Did that first approach to the world of art in any way condition your development as an actor?

Definitely. The ability that plastic art gives you to transport that infinite world of emotions and sensations into images has marked my perspective on acting. I generally draw, I don’t write down the guidelines of the work in my scripts; I visualize the characters with tones and colors that define their path, their scenic expression.

When you came to ENA, did you already know Havana? What connection did you establish with the capital, what was your first impression of the city?

No, I didn’t know Havana. Let’s say it was a double discovery: the big city and its cultural world. I had Enrique Almirante (son) as my first and great friend at the acting academy. His family practically adopted me. The first helping hand turned out to be from a family with high recognition and many relationships in the artistic world.

An infinite range of possibilities opened up in the fields of theater, music, film and television. I received guidance on the most important and valuable aspects of the Havana and Cuban cultural world; I accessed them harmoniously.

The city gave me its charms and, without intending to, I began to make it mine.

What was the process of adapting to the scholarship like?

Scholarship! It was a difficult adaptation, if I can say that I managed to adapt. Enrique Almirante (son) died when he was only 15 years old, and although I always had the love and unconditional friendship of Almirante (father) and his entire family, the stay in Havana was very complicated and I felt like I didn’t always fit in completely.

Perhaps my family upbringing, in which Lidiam Mansferrer and Roberto Llópiz, my second parents, had a lot to do with, gave me an objective and mature perspective, which surpassed that of the average adolescent.

What are the most persistent memories of that time?

Memories of that stage always come back to me. I feel deep gratitude for teachers and fellow students. All my respect to Raúl Eguren, Nikolai Afonin, Nicolás Dorr, Freddy Artiles, Diana Fernández and Nieves Lafferté, to name just a few, to whom I owe a lot.

Do you still have friends from then, colleagues who have followed a successful path on stage?

Certain friends have died prematurely, such as Alberto Pedro, brilliant playwright. Few know that he had exceptional conditions for interpretation.

The vast majority of my classmates, some very talented, disappeared from the scene; either because of emigration, or because reality forced them to look for other paths; we never met on stage again. The least have had significant achievements in other latitudes, which I am infinitely happy about; but not as many as they deserved and I would have liked.

In other specialties such as the plastic arts, I am proud to have the friendship of Arturo Montoto; in music, Argelia Fragoso.… We do not communicate frequently, but we sincerely admire and esteem each other.

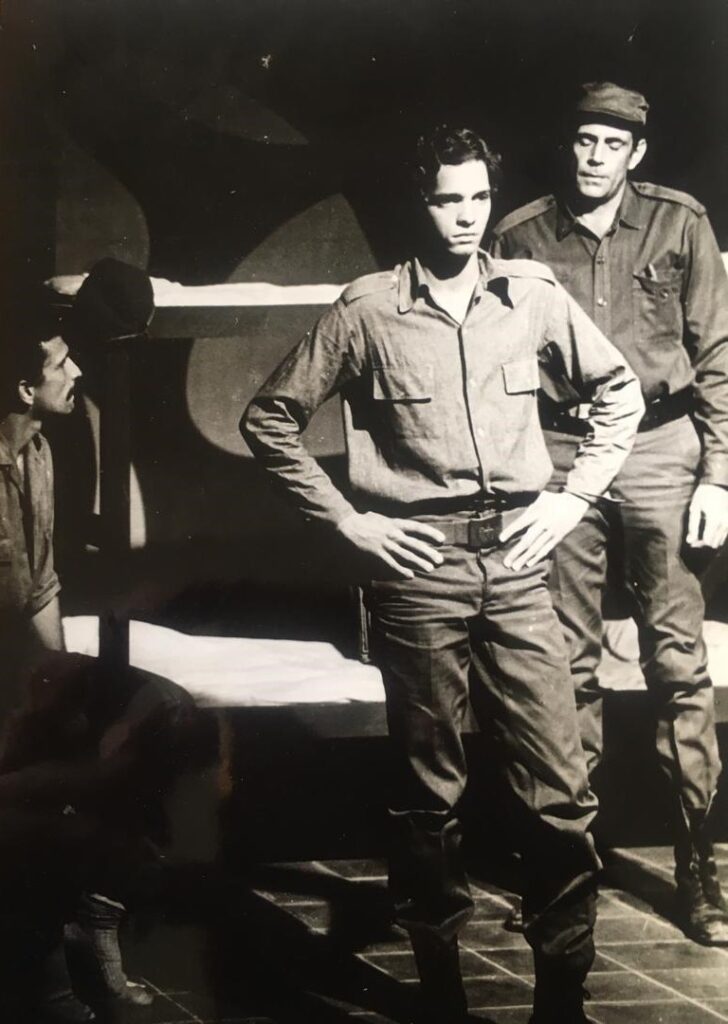

Between 1976 and 1995 you belonged to the Escambray Theater Group. In light of time, how do you value that stage of your life?

The Escambray Group, for many, not just for me, was a second and great school. I arrived for two years of social service and stayed for twenty. It gave me a lot technically, culturally and ethically. It had a solid team of actors, actresses, directors and support staff, which the necessary coexistence for 24 days each month turned into a family; with affections and disagreements, like any family, but where we learned that the priority of the common and voluntary interest of artistic creation provides wise solutions for personal fulfillment, without harming the collective interests, so necessary in theater companies, which, as we know, is an eminently plural art.

If we ignore the economic limitations and stick to the artistic purposes that animated that group, could a similar experience be repeated today?

I have never believed in replicas of cultural phenomena. The Escambray Group is no exception. The reasons that motivated Sergio Corrieri and the fantastic team that accompanied him from the beginning have changed radically; the national reality is increasingly homogenized.

There may be local specificities, but not remotely like those of the late 1960s and early 1970s. Therefore, without giving up attention to the spiritual needs of each corner of our country, where the wealth of artistic and cultural work in general continues to be vital, I believe that even today, more than ever, new solutions must be sought in accordance with the socio-economic and cultural moments that our country is experiencing.

Does this theater with an anthropological vocation, which is based on the investigation of the reality of a specific population nucleus to discuss its most pressing problems through art, correspond to the interests of the playwrights and actors of this time? Has the mystique that animated collective creation groups been lost?

The need to discuss pressing problems is a constant in art, and in theater specifically it is the backbone of creation. Therefore, this anthropological vocation is always present, and anyone who wants to write for the Cuban or universal scene must have a powerful knowledge of the social phenomena that they try to capture in their work, to critically, deeply, bravely and respectfully reflect the reality that surrounds them.

Likewise, collective creation, although not in the same sense that was used in the past, but with that collaborative and contributing character that theater demands, was, is and will be present forever.

Even in productions where the directing mechanisms of the plays follow orthodox paths, the contribution of individual nuances, as long as the seriousness and deep respect that theatrical creation demands prevail, foster an invaluable collective character.

Since 1995 you belong to the theater company El Público, directed by Carlos Díaz. It is a group that is among the two or three that are at the forefront of current Cuban theater. In its time, Escambray was also a collective that set the standard for what was considered artistic excellence. It seems to me that both groups are at opposite ends. Is that so?

I know that I am enormously privileged to have belonged to Escambray Group and now to the Público; both companies have entrusted me with an important role in their projects, so the process of learning and artistic maturation is permanent.

The supposed diametric differences between the Escambray and the rest of Cuban stage production have been the subject of historical discussion; but technical assessment has almost never taken precedence in these analyses. We were talking a few moments ago about the validity of anthropological concern in theater; but isn’t it inherent to all theatrical creation throughout history? It was in Shakespearean theater, in Grotowskian, Barbian studies, or in the work of Vicente Revuelta with Los 12. Do the technical rudiments of the actor, in addition to aesthetic tendencies, have no common basis?

We could make a whole postulate about it, but I am convinced that it is not the meaning of this interview; however, from my personal experience, considering myself an actor with an absolutely Stanislavskian training, I can affirm that joining both companies has not implied, in any way, a break with my technical training; but it is an expansion of the acting resources based on the aesthetic precepts that each company defends.

What does being part of the cast of El Público mean to you?

El Público is my most precious means of feedback with today’s Cuba, and the ideal mode of expression as an artist and as a Cuban. I am honored to be an actor of El Público.

What have been your most notable performances with that troupe?

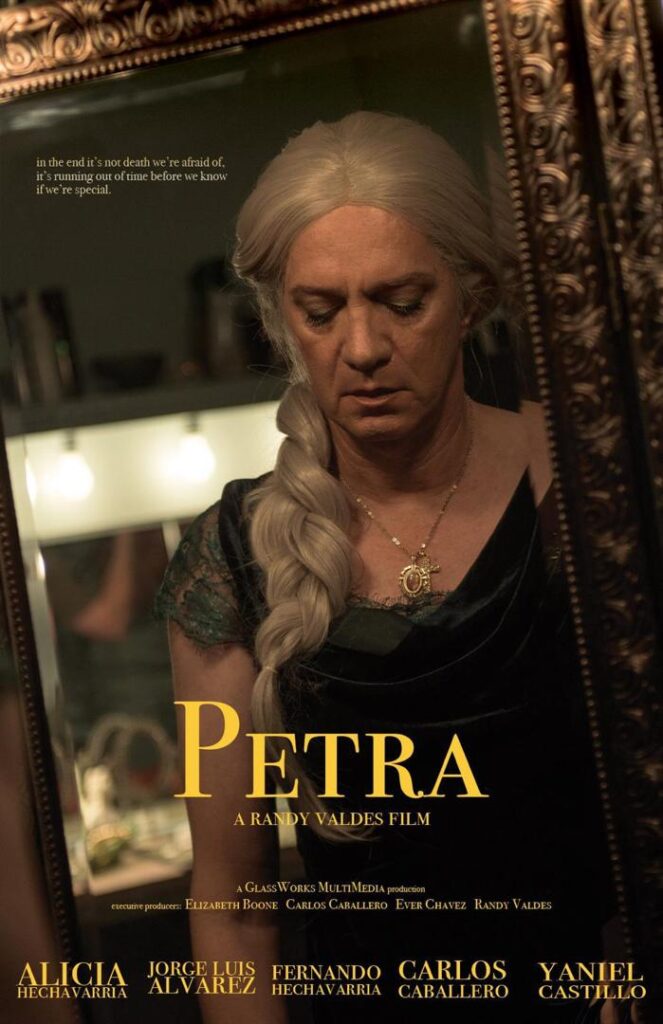

Among the most relevant performances are King Lear (Shakespeare), Querido Diego (Senel Paz), Caligula (Albert Camus), The Seagull (Chekhov), Squad to Death (Alfonso Sastre), The Bitter Tears of Petra Von Kant (Fassbinder).…

At this moment we are immersed in the performance of Réquiem por Yarini, the classic text by Carlos Felipe.

You have done theater, film and television. I think that the greatest popularity has been granted to you by this last medium. Are you one of the actors who needs to feel the vibration of the audience in the irreversible instant of the room or are you one of those who prefer to have the camera as the first witness of their performances, since scenes can be repeated over and over again in search of perfection?

I definitely value the vibe of the audience a lot. Each medium has channels to establish that wavelength, but I love that direct contact with the viewer that only theater offers. It is true that audiovisual media give the possibility of perfecting the work in each take, but the theater offers you time and rehearsals to embroider the characters, and then the continuity of representing them on stage from beginning to end, making each performance something unique and unrepeatable, with the complicity of the public, who treasures that gift for life in their minds. Perfection is a moving challenge in theater.

Let’s talk about cinema. Arturo Sotto has called you for four of his films: Amor vertical (1997), Pon tu pensamiento en mí (1995), La noche (2005) and La novicia jardinera (2021). It is evident that he has high regard for your work. Is it a reciprocal feeling?

Arturo Sotto values my performance, and of course that feeling is reciprocal. Due to his acting training, he knows how to ask his actors what he needs each time, making them complicit in the creative process, without unnecessary pressure and with extreme respect.

Sergio Giral has just died. He was a filmmaker who, I think, has not been given all the importance he has within national culture. His films were pejoratively called “black films.” There are El otro Francisco (1974), Rancheador (1976), Maluala (1977), Plácido (1986) and María Antonia (1990), just to mention some of his long fiction works. How do you remember your participation in Plácido?

Unfortunately Giral is not the only case —no less regrettable— among those forgotten; this is causing a worrying lack of referents in the new generations. At some point we will have to rethink this procedure, because it is in diversity where wealth lies.

I remember my short, but significant participation in Plácido with great affection; I had the opportunity to work there with iconic national figures, such as Ramoncito Veloz, Mirtha Ibarra and Jorge Villazón.

Giral was a man of cinema, in the broadest sense of the word, and working with him was tremendously pleasant and instructive.

I am going to mention some plays in which you have had an outstanding participation. Among all of them, point out the one that you remember most fondly, the one in which you believe you have reached the highest acting level and the one that had the greatest reception from critics and the public. You can point out others that I do not list: La vitrina (Teatro Escambray, Dir. Elio Martín, 1990), Molinos de viento (Teatro Escambray, Dir. Sergio Corrieri, 1992), Electra Garrigó (El Público, Dir. Raúl Martín, 1996), La gaviota (El Público, Carlos Díaz, 2001) Chamaco (Argos Teatro, Dir. Carlos Celdrán, 2006) and Fedra (El Público, Dir. Carlos Díaz, 2007).

We have our characters as children and they are all loved equally; but at the level of critics and the public, Molinos de viento, Calígula, El Público (Carlos Díaz, 1996), Chamaco and Las Amargas Lágrimas de Petra Von Kant, mark a milestone in my theatrical work.

Among your performances for television that have had the greatest public resonance are Cuando el agua regresa a la tierra (Mirta González, 1991), Tierra brava (Xiomara Blanco, 1997), Las huérfanas de la Obra Pía (Rafael González y Nohemí Cartaya, 2000), Salir de noche (Mirta González, 2001), Doble juego (Rudy Mora, 2001), Historias de fuego (Nohemí Cartaya, 2006) and Hermanos de sangre (Ernesto Fiallo, 2015) and Asuntos pendientes (Felo Ruiz, 2021). Is Nacho Captain still the most popular character you’ve played? Is television, as they say, a minor genre?

Tierra Brava is the turning point of my television work. It had a definitive popular impact; without a doubt, due to the quality of Xiomara Blanco’s direction and the confluence of a larger cast.

I must thank Mirtha González for the possibility of understanding that television is art; it only depends on the commitment, love, respect and devotion with which we face its realization. Cuando el agua regresa a la tierra or Aire frío are examples of this, and without a doubt two of my most relevant forays into television. Likewise, working with Rudy Mora is and will always be proof of how valuable the television medium can be, aesthetically.

I have always thought that to teach any artistic discipline, the teacher’s mastery of the subject is not enough. The bond between master and disciple artists is very unique, where admiration, complicity and total empathy have to prevail. What do you think of this after more than twenty years of teaching?

Teaching is one of my passions. I am certain that I am not fully qualified for the pedagogical exercise of theater, which is very complicated, but it is one of the ways to repay what so many have done for me.

We agree that it is not enough to know the subject you teach; the teacher-student bond and empathy in the classroom are very important (understood by classroom not only the teaching space, but all those spaces in which you work and exert influence on those generations, including private life). Being ethical is essential, and even defines the final course of our careers; therefore, it is vital to practice what one preaches and, above all, encourage the individual growth of each budding artist, our students.

The most important thing is to guide them in self-knowledge, in the discovery of their potential, so that they develop them. It is not a question of mimetically repeating our achievements, but of achieving their own based on their own values.

What is it like being the father of Alicia Hechavarría? Are two actors a crowd in a house?

My family is my great treasure, and our daughters, the greatest work. Being the father of Alicia and Patricia is a divine gift. In Alicia’s case, we share a passion for acting and I am proud of her successes more than mine.

Our relationship has always been based on love, of course; but also, respect and sincerity; therefore, two is complicity, not a crowd.