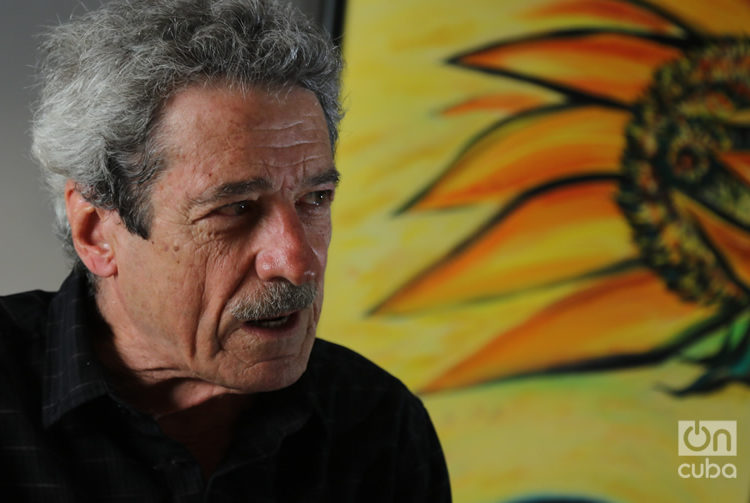

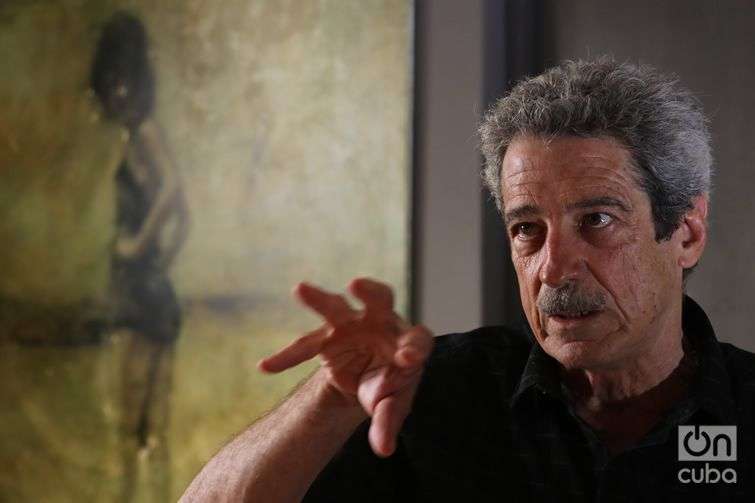

If there is someone for whom Havana is a set that is Fernando Pérez. Here are his films, brewing in plain view. He feels them and he films them: Clandestinos, Madagascar, Hello Hemingway, La vida es silbar, Suite Habana, José Martí. El ojo del canario, Madrigal, La pared de las palabras, and announced for next December is the premier of Últimos días en La Habana, his most recent production.

Fernando Pérez talks with OnCuba and describes his film as a “happy drama” that started having a title only apt for Cubans. “In this film, for reasons that the spectators will discover when they see it, the title ‘Chupa pirulí’ [Lollipop licking] attracted me a great deal. The immediate reaction was laughter or confusion. ‘Is it a comedy?’ ‘No, it’s not a comedy, it’s a happy drama.’ And the confused would say to me: ‘But that isn’t one of your films.’” Co-producer José María Morales advised that a second title be found, more “international,” and that’s how Últimos días…came up, which when screened in Havana will keep the wink of the initial title.

Últimos días en La Habana or Chupa pirulí hopes to represent the drama of the major part of the Cuban population in its survival, “where there are many problems, many dark days, but in which, despite this, Cubans manage with a positive charge that balances and prevents the crisis from being greater.”

That duality in us, the Cubans, is not only seen as a virtue, it has also been criticized as a defect.

I thought about that when making the film, but I didn’t work that aspect. Its fundamental charge is not criticism. I didn’t want to criticize the characters or the reality; I wanted to show them as they are in their complexity, in their ambivalence. Somehow, the intention is to make Suite Habana 10 years later and in the fiction style, with characters that are in the same environment, but living it another way.

It is a fiction movie, with well-known actors like Jorge Martínez and Patricio Wood, trying to maintain an impression of reality, because it is an absolutely realistic film. Its language does not privilege too much the symbols, the metaphors…. Although there are times where it also opens up so spectators can participate in individual, subjective associations. It is a very unassuming film. The subject of the film is prejudices and the relativity of the moral values at all levels.

Is it inspired on certain persons, or it is a mixture of several?

What attracted me about the project presented to me by Abel Rodríguez, a young amateur writer that got to my home with the core of that script, was precisely that they were real characters, in an environment that has to be well-known from within to be able to write about them. And that’s what we have tried to maintain in the shooting. Últimos días…had to make the characters credible through good actors capable of making good characterizations. Diego, the protagonist, is in the final stage of AIDS; Miguel is a very introverted character.

The fact of not appealing to difficult or too symbolic metaphors, aspects that have been very persistent in your work, means a mutation of Fernando Pérez?

In my first two films, Clandestinos and Hello Hemingway, I felt I had to prove myself that I was capable of telling a story and making the characters credible. Handling a symbolic language, expressing the subjectivity of the characters, their psychological depth, were for me the most important when I started making movies.

Today I believe it’s equally difficult to make a fiction film. With Madagascar I wanted a realistic language; I wanted to delve in depth into the imprints that the Special Period was beginning to leave on my generation and on that of my children. That’s why I started working the metaphor and from there I continued with La vida es silbar and Suite Habana which, even while being a documentary, resorts to an associative language and has sequences with many metaphors.

Then there was Madrigal, where there are associations, metaphors and barehanded symbols…. It is my accursed film. I like it but almost no one likes it. José Martí… is again a fiction film and the same occurs with La pared de las palabras, where life stories are told, but there are situations and sequences that invite the spectators to make readings that do not directly emerge from the story told.

With Últimos días en La Habana a bit of that occurs. It is a minimalist movie, one of the challenges for me was even the long sequences and I want to see how the spectators react to this. There are no recherché mise-en-scenes or that are too built up. It aspires to a very impeccable communication with the spectators, and that they forget they are watching a film.

Many of the sequences were filmed with a hidden camera in the street. That is something I am doing since La pared de las palabras, I do not include extras. And, actually, people let themselves be filmed here in Cuba. That is priceless.

Which Havana appears in the film, taking into account, moreover, that it is a city in fashion?

The Havana I walk the most, which is Centro Habana, Cerro, Pogolotti…. The Havana that is defined as the deep Havana, which is the most representative but the less represented in our media and in the media abroad. And when it is represented, because Rihanna is coming, it is stylized; because the ugly and the dirty can have beauty and can become a mise-en-scene.

We toured, looking for locations, a great many tenement houses and in each one the same inhabitants, the same experiences are repeated. In the tenement house where we filmed, the neighbors’ collaboration was special. That’s where I most like to film. It is a space where I feel there is a barometer to take the temperature of our reality, more than in the official or other media. But you have to live it.

Are you seeking some immediate reaction with this film? What is the citizen filmmaker trying to do with this film in 2016?

I want to share what I feel, what I see, with the people that surround me, with those of us who are here, as well as with those who aren’t here, and discuss and reflect about that. I’m not one of those who believe that a film changes reality, but I do think it helps to create an awareness, to get a feeling about that.

There are Cuban films that, in key moments of recent history, have been like a kick in the teeth. Strawberry and Chocolate was one of them, just like Suite Habana and Conducta. Could this film have the same effect?

That depends on the spectators. I thought Suite Habana was going to reach a public that was less wide and, all of a sudden, the film went way beyond those expectations that I had. It was a lesson. I believe that to a great extent the circumstances also determined. It was Suite Habana, but also the moment. It could have been a play, a song or any other thing. But it was the film that appeared at that time and it was synchronized with what the people felt. For me, each film is a risk. I see it and I recognize myself in what I did. But I don’t know what’s going to happen with it.

Fernando Pérez has a leading position, not just artistic but also as a human being; he is like the island is for many shipwrecked people, where you can arrive and save yourself. Do you feel it like that?

No. No I don’t see it like that, for me that is too much. If there’s something I aspire to, it is to live my life as unassumingly as possible, in harmony with my daily things.

A train, the sea, the rain…. Are they in Últimos días en La Habana?

There’s the city, there are no trains but there are ships, which I added at the last moment. And, inevitably, the rain and the sea.

Then, it’s the same Fernando Pérez….

Yes, although there are some sequences that are going to say: “Is this a film by Fernando?”