Q&A with Seven Cuban Artists is the first Cuban contemporary art show held in Washington in recent years.

The gallery in the International Development Bank will house the exhibition this December, in the same month of the anniversary of the beginning of normalisation of relations between Cuba and the United States.

OnCuba talked with the curator, the art critic Cristina Vives, co-founder of the independent project the Figueroa-Vives Studio.

Why play with the idea of “questions and answers” for the name of the show?

Putting together an exhibition of Cuban art with the eagerness with which Cuba is being consumed today is very easy. You put a bunch of names of key artists, you mix in the ingredient of different aspects like Afro-Cuban religion, stereotypical images, the idea of exile, etc. A couple of likeable, interesting works that will be welcomed in this context. Really easy.

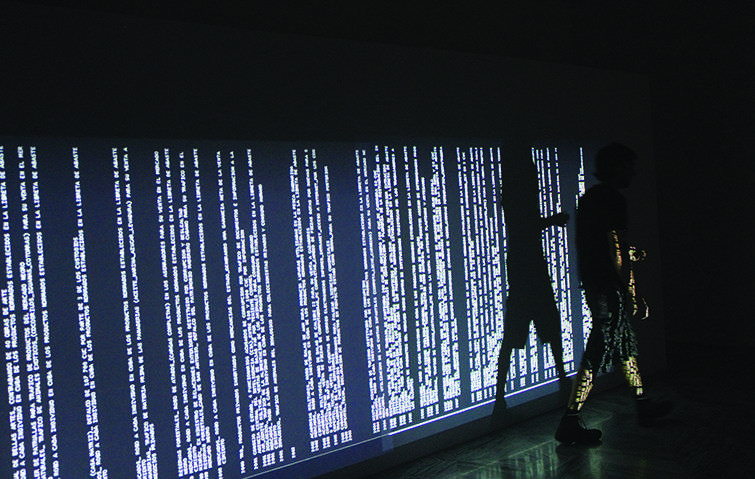

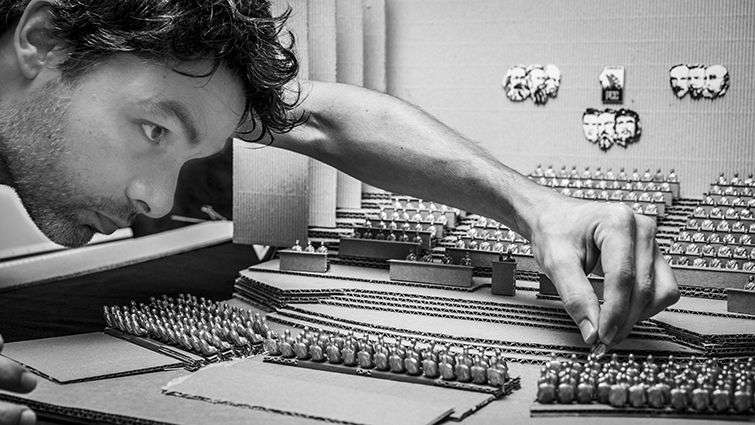

But, if the idea is that a collective Cuban exhibition right now cannot be pleasant, you have to question things and include a sector of Cuban artists that might be interested in problematizing rather than responding to the image that Cuba has or is thought of having. Something that could be unexpected.

Personally, I find themes that have analysis and reflexion at their core interesting. How I see myself and not how others hope to see me. Revisiting history with a critical eye. I’m interested in the corruption levels in my country, in the economic levels, the manipulation of public opinion or how the rest of the world see us as a trend. I’m interested in how the average person lives in our country.

I wanted to ask questions, what is news in Cuba? Q&A…is an exercise in curation through which I ask seven contemporary Cuban artists about their obsessions, their doubts and their interests. Their answers should take you directly into their works.

Is it possible that in Cuba they could think you are exporting a negative image of the country?

No one with any common sense would defend a nice, idyllic exhibition. This is a country with serious problems, to the point that even the official discourse has said what these problems are. Art cannot be removed from this. Because of this, we offer a vision of issues at the core of society through art.

The exhibition does not give a negative image of Cuba, but a lucid analysis of the real problems. It talks about the critical capacity and reflexivity of these artists as Cuban citizens.

Wouldn’t you like to exhibit it here in Cuba?

Many of these pieces have been exhibited individually in institutional spaces in Cuba, in art biennales…others have been created specifically for this show. But it is the bringing together of these pieces that give the exhibition its sense of criticism and reflexivity that I was looking for. And that is how the dialogue between the pieces begins and their essence grows. Of course, it would be very interesting to put them together and exhibit them in Cuba as well.

The gallery

The International Development Bank (IDB) was created in 1959 to finance projects in Latin America. It has a Cultural Centre that promotes art and exchange in the region, and it is two blocks from the White House.

But why is the IDB interested in a Cuban art exhibition? Why a county that does not participate in its operations in American territory?

For Trinidad Zaldívar Peralta, head of the Department of Cultural Affairs, Solidarity, and Creativity the answer is linked to the sense of curiosity towards the island that began on December 17 .

“We wanted to present a fresh, poly-faceted vision of an island to a public that is more accustomed to imagining a nation, as if it were a black-and-white photograph stuck in time,” Zaldívar told OnCuba.

It took eight months, from the decision to take Cuban artists to the US capital, to mounting the exhibition in the IDB gallery. “The premises were clear: very high-quality art, a first-class curator, and artists that were not just young but also lived and worked predominantly in Cuba. Our intention was to be part of the cultural dialogue that was slowly beginning in the country but that we do not see in Washington, DC,” she said.

Cuban culture, according to Zaldívar, despite being well-established and forming part of the Latin American and Caribbean scene, does not have a visible presence in Washington, where participation in the city’s organisations’ art programmes was inexistent or very restricted. “The events of the last 12 months made us thing that these walls were already more imaginary than real,” she said.

“It seemed to us that bringing a demonstration of contemporary Cuban art and young artists from the island to the Bank and to Washington was a gesture, a contribution towards building bridges, breaking down preconceived images and opening up a dialogue,” she concluded.

The exhibition will run through the first week of March 2016.