If you doubt there is art collecting in Cuba, you have to meet Juan Carlos Romero (Havana, 1964). Or maybe you have, but don’t know about the treasures that this professional photographer jealously keeps in his house in the former industrial neighborhood of Luyanó.

On three occasions he tried to enter the San Alejandro Academy (1985, 1986, and 1987), and each time the same thing happened: he passed the drawing tests with flying colors, but, in his own words, he “was defeated by the color.” So he took the camera and, since 2004, began photographing artists and works of art for specialized Cuban publications, until in 2016 he started working for the National Museum of Fine Arts, where he remains to this day.

It’s difficult to work in the field of contemporary Cuban art without going to Juan Carlos’s photographic archive. He is also good at giving references and fostering contacts since his helpful and smiling disposition opens all doors. Proof of this are the impressive collections that he has been putting together, many of whose pieces come from his frequenting artists, with whom he usually forges a relationship that goes beyond the professional.

I knew about his “Retablo cubano” (Cuban altarpiece), but my information was fragmented. So we met at my home on one of these days of the indecisive Havana winter to talk about our common passion. The dialogue, zigzagging, jumped from one topic to another, from one artist to another, from one work to another that hangs on my walls. Still, I managed to corner him journalistically.

Retablo cubano

The collection began to be conceived in 1994 when he was documenting the work of Roberto Fabelo, who at that time was putting together a kind of altarpiece with interchangeable pieces painted on wood. Romero then set out to create his own altarpiece but from the collecting angle.

His would also be works on wood, measuring 15 x 15 centimeters, due to all those Cuban artists who were able to contribute to the project. At first, it would be one piece by artist, but some of them welcomed the idea so warmly that they delivered several works; even, with time, and seeing the importance that the altarpiece is having, some have asked to replace their original contribution with another “of greater importance” and more recent.

I think that by now it must have been clear, but I still emphasize it: the 532 paintings collected so far, due to 520 artists — from inside and outside the island — were made expressly for Juan Carlos’ collection.

I ask him why the Retablo has never been exhibited…. He tells me that he has had proposals to show it outside of Cuba; but the collection must begin to “walk” here, in its own cultural sphere. In 2024 something may be finalized with the Fábrica de Arte Cubano (FAC); also interest has been expressed from the United States and Spain.

Juan Carlos thinks that the Retablo…will have a long journey, and he patiently prepares for it. I want to know when the collection will close. He smiles and answers with another question: “Is there an end to Cuban art? It continues to grow, adding consecrated people who have ‘escaped’ and emerging ones, showing the plural richness of a manifestation that expresses us in our singularity and with our deep contradictions. This note for OnCuba,” he concludes, “is kilometer zero of a journey that begins now.”

Martí, bills, sharks

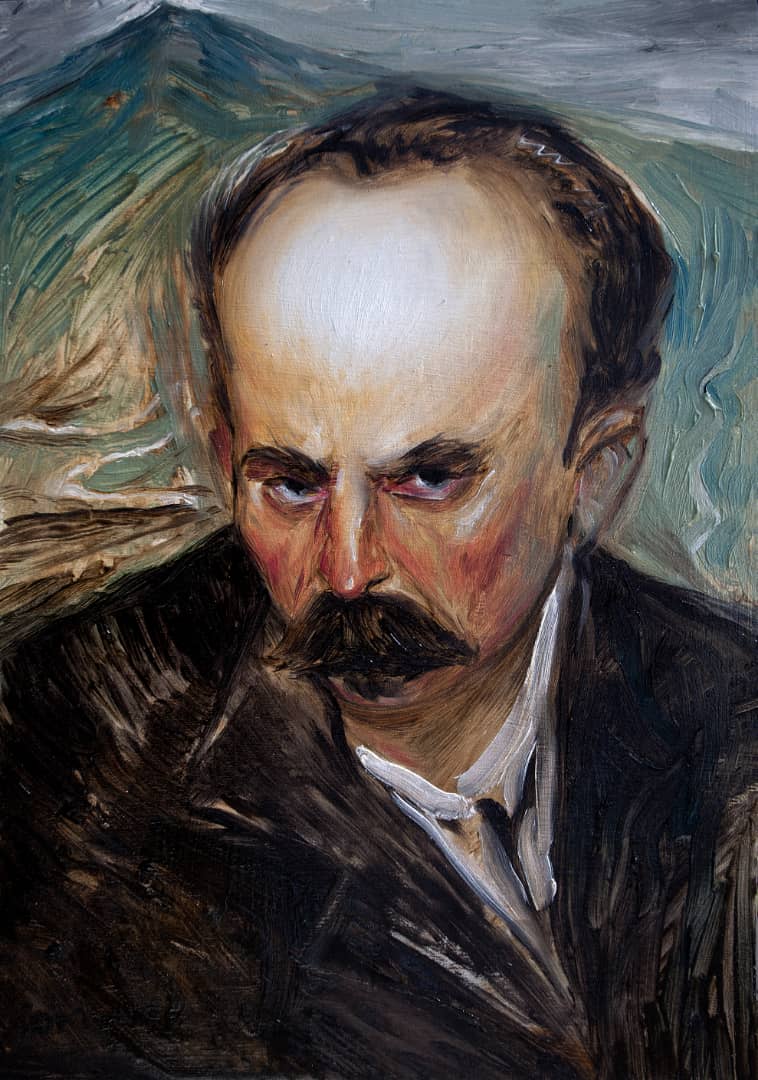

Although as a collector Juan Carlos accepts himself as eclectic, three other thematic lines move him: José Martí, sharks and the intervened paper money — not only from Cuba. With the theme of Martí there are, so far, 50 works; there are 20 that have sharks as their center, and there are 197 intervened bills.

The collection of banknotes began with Cuban paper money from before 1959, but then extended to the present day and even includes pieces from other countries illuminated by artists from those places, who empathize with the Cuban collector’s fervor.

I want to know what the jewels, in a broad sense, of his patrimony would be. He tells me that there are very good paintings that are not subject to any of the themes we have been talking about, but the apple of his eye is the Retablo…. He refuses to cite authors, because, if he did, he would have to include the complete list, without discrimination or forgetfulness.

Anyway, I ask him about the pillars of our art to know if they are represented: Sosabravo, Mendive, Fabelo, Nelson Domínguez, Zaida del Río, Forst, Pedro Pablo Oliva, the national awards for Plastic Arts… He says yes to everything, but does not give many details.

“Will you go to the inauguration of the Retablo cubano in Havana, when this is finalized?” he asks me. I tell him that of course, I would try to write about the event and that I modestly offer to write the words for the catalog. He extends his hand to me, and with a Cuban smile, he blurts out: “Then you will have all the details.”