At the end of December 2023, we published a conversation with the economist, professor, and OnCuba columnist, Juan Triana Cordoví, in which he took stock of the year about to end and made a definitive prediction about what awaited us: “2024 is going to be really tough.” And so it has been.

During that interview, which already has nearly 40,000 views, we agreed to meet again to talk by video call about current Cuban economic events.

In these six months we have had blackouts, protests, a small rebound in tourism, more than 11,000 MSMEs approved; a former minister of economy “rigorously investigated” for “serious errors” — which have not yet been explained — “in the performance of his duties,” and a new minister whose name few know, due to lack of press coverage.

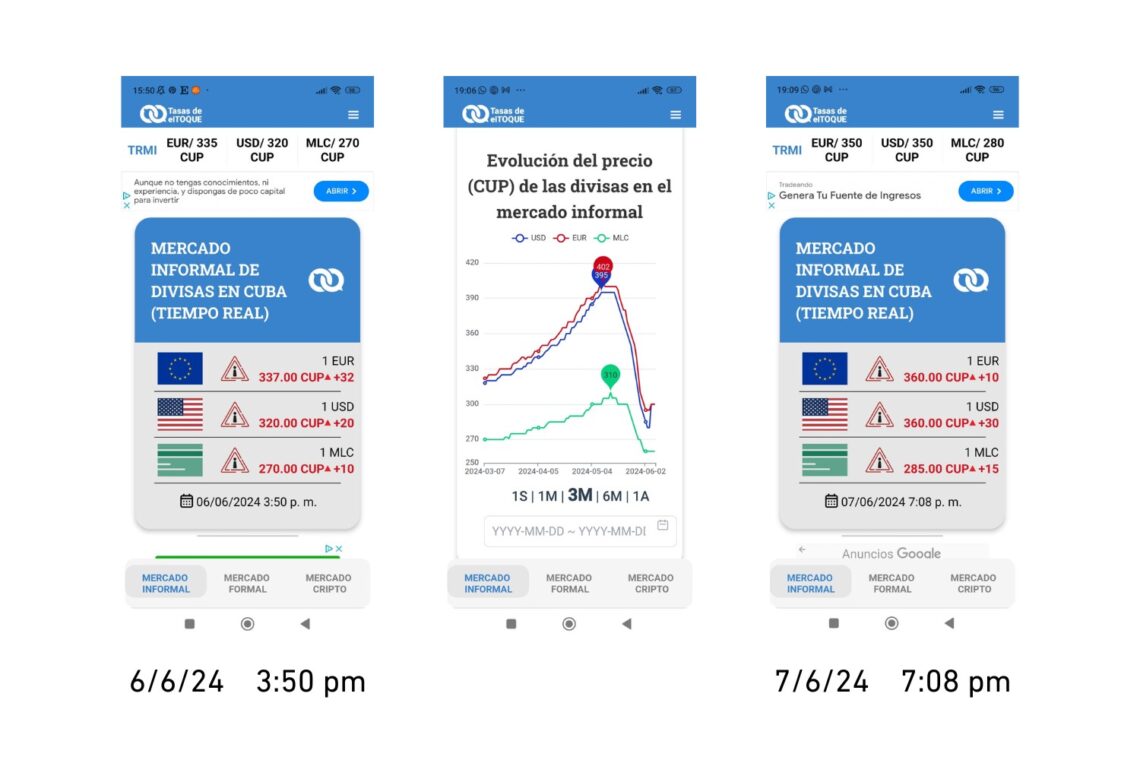

Among all this, what has perhaps sparked the most attention and multiple debates in recent weeks has been the movement of the exchange rate between the dollar and the Cuban peso, which after reaching the peak of 400 pesos per dollar, then plunged to 280 in a few days, to resume climbing again, according to El Toque.

While we were talking, yesterday, June 6, the dollar was at 320 pesos, according to that record of the informal market in real-time. A little more than 24 hours later it already reached 360. How much will it be next Sunday? Presumably, it will skyrocket again. How far could it go and why is it something we all ask, sometimes trying to emulate fortune tellers?

The issue has been so controversial that El Toque published its decision to “strengthen controls to calculate the representative rate of the informal currency market.”

What happened? What are these telluric movements of currencies about that make people try to explain the causes, the reasons, the results, the consequences? What is your vision of the matter?

What happened? What are these telluric movements of currencies about that make people try to explain the causes, the reasons, the results, the consequences? What is your vision of the matter?

I would start by telling you that in these six months, there are also specific improvements in tourism, which is very good. There are improvements to some export issues; as well as a prospect of improving the price of nickel. But there really are no improvements of the magnitude that would allow the Cuban family to reach those improvements.

What has happened to the exchange rate is due to several factors.

The first thing to say is that there has not been any significant change in the causes that have motivated a rise and galloping inflation and that upward volatility of the exchange rate in recent months, the objective factors that influence the exchange rate…

We continue having a significant deficit and that generates liquidity, which is one of the causes of the increase in the exchange rate, because it increases liquidity without material support.

We have not had a significant reaction from the Cuban productive system. Especially in the agricultural sector, which I would say is the one that is, unfortunately, leading the increase in prices, up to 60, 60-odd percent. There is no substantial increase in supply and, therefore, if supply does not grow and production does not grow, it is another of the objective causes that can generate inflation.

Well, obviously the exchange rate is not going to be reduced. And on top of that, we have people’s expectations.

All of this acts as an ajiaco, that is, a mixture of objective causes along with expectations.

What people’s expectations do is anticipate the rate. That is, if there is an upward trend in the rate and I am going to sell or buy dollars or sell or buy products, what I do is anticipate the rate. It’s the Ockham law in the end. In other words, since I’m thinking that the rate is going to go up, the rate goes up. And since I’m thinking that the rate is going to go up, I advance the rate. Instead of the exchange rate, for example, that El Toque estimates, I estimate the exchange rate of El Toque plus 10 pesos. And when many people do that in a row, logically the rate shifts.

Or 10 pesos less.

Yes, it can influence both upwards and downwards. What other factor do I think has had a huge impact there? The fact that there is a gap in regulatory terms. There is no intervention instrument like there was before, which was the Cadeca exchange offices, which could intervene in the money market and could somehow regulate the rate. The great success of Cuban monetary policy for a long time was having maintained the stability of the exchange rate between the Cuban peso and the dollar and later between the Cuban peso and the CUC.

That was achieved for a long time, almost from 1996 to 2019. The exchange rate was stable and that is very good, and it is very good for business.

The instability of the exchange rate, especially an exchange rate that is so volatile upwards, ultimately causes business to stop.

The other factor that somewhat influenced the drop in the exchange rate, in addition to speculation, was the fact that importers, especially private-sector importers, refrained from importing the same quantities as last year. Because? Because of the uncertainty.

If you import at an exchange rate of 370 pesos per dollar, and when your merchandise arrives at the port a month later or 20 days later, the exchange rate is 390, you are already losing 20 Cuban pesos for every dollar of imports.

You mentioned it and I have been seeing how most economists agree that the exchange market is racing. Pedro Monreal, for example, just published today in a tweet the idea that there is an “abandonment of state functions regarding monetary policy.” Julio Carranza has said that “the Cuban State neither controls nor regulates the exchange market, simply because it does not participate in it.” It is a key factor in what you say about businesses that stop or are affected because they subsist in a non-regular, illegal exchange market.

I totally agree with Pedro and Julio. We agree on many things, actually. One of the factors that generate this volatility is exactly the abstention of the monetary authorities from intervening in the money market. I know it is difficult because perhaps they do not have the necessary backing, but the vacuum of the monetary authority creates space for unlimited speculation.

That is my experience this month — I have been very aware of this because many people write to me.

For example, yesterday several MSME owners wrote to me saying: “Professor, I am responding to people who are offering me 350 dollars. When I call them, they tell me they don’t have any.” In other words, what there is is an exercise in speculation, of course. Very clear. And people are trying to counteract the decline in the dollar because it is not convenient for speculators, they lose money.

The impact on the real economy, on supply, is negative. The impact on the family economy is negative.

Supply contracts and people can consume fewer goods and services they need.

And it will impact the growth of inflation. At a certain moment, the supply may be greatly reduced. My experience ― once lived in a country in the southern cone ― is that of arriving at a supermarket and seeing it closed due to lack of prices.

How is that?

The volatility of the exchange rate was so high, so high, that you would grab a soft drink on the shelf, and by the time you got to the checkout the price had already changed. What was the response from the merchants? To stop. “I don’t continue doing business because I don’t know what price I’m going to sell at.” What in classical microeconomics seems shouldn’t happen, which is that a product has no price, happened. Something similar is happening in Cuba.

Now that you mention prices, the majority of the Cuban population when they need to put a price on something, resorts to the El Toque rate. For example, a bricklayer puts some slabs on your wall and you ask him how much he will charge. And he tells you to wait a moment and searches his phone, and based on the price of the dollar at that moment, he puts a price on his service. That is to say, this operation of setting prices based on what you see in the El Toque rate specifically is a very daily operation in Cuba. What relationship does this speculation dynamics have with the dollar, which, by the way, is a commodity in deficit, with the rest of the markets that coexist in Cuba, for the purposes of prices? Many people were waiting for a price drop that did not come.

The price reduction on some products did take place, but it did not come massively because those products were purchased at a rate of 390. And if you negotiate at 390, it will be very difficult for you to lower the price, unless you accept to lose.

Now, you can imagine that whoever buys a container of oil and loses 20 pesos on each bottle of oil is losing a lot of money. That is a problem, without a doubt. Therefore, not all prices dropped; although oil went down a little, eggs went down a little, some prices actually went down, momentarily.

Because, in addition, some small and medium-sized enterprises really proposed, even if they assumed the loss, to lower prices, which was very interesting for me, because in some way it meant an element of incredible social responsibility.

Is that sustainable over time? Could there be an intention to participate in the market by imposing a price that way, by agreement?

Maybe not very sustainable, but it is possible. Prices can be agreed upon by a group of people who also set prices. It can perfectly be done.

If it can be done for the price of eggs or oil, it can also be done with the price of the dollar.

Well, that’s definitely what’s happening today. I believe that many buyers and importers who were harmed agreed to have a more favorable exchange rate. In fact, there were many messages of “I’m not buying more dollars at the price of El Toque, but I’m going to buy them at 350.” It’s over.

That happened a lot at the beginning of this movement. Obviously, everything has a limit because there are really no changes in the real economy. And there is no intervention from any monetary authority. And this is a very special money market; it is one of the things that, above all, I would like people to be clarified about.

I have nothing against the methodology that El Toque is using to capture exchange rate information. But I have to say, definitely, that this information is about purchase intentions. El Toque also says it. And you never know if those purchase intentions come to fruition or not.

It is a void that exists. And therefore, people are guided by the exchange rate of El Toque; because there is no alternative exchange rate at this time. And that is a void, that is a neglect of monetary functions.

Is it possible that in the short or medium term, there will be a downward correction of this exchange market volatility, let’s say, that the peso will be better balanced against the dollar, without the participation of the monetary authorities in it? Whether by selling dollars or legally allowing private bidders in the exchange market, paying taxes, etc.? Is it possible that without these elements the volatility of that market and all that speculative effect, that bullish speculative loop, can be corrected?

I think not, and life has shown it. Regulation from the monetary authority is essential to maintain the stability of the money market. Anywhere, that is essential in any country in the world. Whether it is done one way or another is debatable.

I have proposed as a solution the formalization of informal operators who buy and sell dollars because in my opinion in today’s market, the monetary authority cannot intervene in a powerful way, because perhaps it does not have sufficient resources. Formalizing a group of informal operators could be, above all, something positive, in the sense that we would know what the real concrete operations of selling and buying dollars are. We would know what the supply is, what the demand is, what the volume traded every day is. And, based on that, we would have a much more objective exchange rate than the one we have, which is purely speculative.

Everyone is waiting. Someone today told me: “Wait for Sunday because on Sunday it is already at 400 again.” Because now it is rising 20 by 20, 25 by 25, in an extraordinary climb. How far will it go? Who knows?

They stayed for two days, but Cadeca held out and the money changers had to lower the rate. Because for the Cuban people, the reference was the Cadeca rate.

If at the end of the year, this does not change, would we be talking about a greater irresponsibility of the Cuban monetary authorities and, in general, of the Cuban authorities, in not intervening in this dynamics?

I believe that the monetary authority’s neglect of the money market correction functions must be corrected. There is no other option. And there are options to do so. There is a range of options.

This is not a very difficult money market. I would say that between 70 and 80% of monetary exchange operations in Cuba are carried out in the Havana market. I remember that in the Western Union information (from the 2000s) they said that 25% of the remittance stayed in Havana and the rest was distributed among the rest of Cuba’s provinces and the municipalities; no province had a participation greater than 7%. Look how simple it is.

Today, if you look at what some of the platforms that sell products do, they can tell you that between 75 and 80% of the sales volume in Cuba, of what they do, is in Havana. In other words, there is an important concentration. That is data that can be used to intervene and stabilize the money market.

Because I repeat, this destabilization, this unbridled race, upwards, due to the effects of speculation and the intervention of speculators in the Cuban monetary market, harms everyone and logically harms the credibility — what we have left — of the national economy.

When you say that it affects everyone, you are not only referring to the government, its network of enterprises and institutions but also to those who oppose the government. That is, to those who propose a completely different economic agenda, let’s say, for example, a liberal one, towards a capitalist order that transcends the socialist order.

Inflation hurts everyone. It harms the economy of a country.

It harms Cubans who live outside Cuba, who remit products or money to their families.

Also.

Because when they used to send a dollar, that dollar had a greater purchasing power than it has today. Now they have to double or triple their remittances to address the needs they are trying to solve in Cuba.

Exactly.

Either this is seen as a general issue for everyone and we transcend the conspiracy theories of the sides or, simply, from what I am understanding through your words, it will continue to be a great disruption that is difficult to solve, with greater incidence for those who are most suffering in Cuba, those who have less purchasing power.

I don’t like to say that phrase, because it is a very typical phrase of the most classic, most orthodox current of monetarism; but there is an important phrase: “Money matters,” monetarists say. And money matters and matters more. Because the price of money cuts across the entire economy and affects everyone in an economy. Logically, it affects the poorest the most.

This price of money, this uncontrolled speculation, impacts the poverty situation of the Cuban family. And the examples are simple. In Cuba, there are more than 600,000 retirees who receive 1,500 pesos from their pension. When the carton of eggs costs 3000 pesos, they have to buy half a carton of eggs.

They need two pensions to buy a carton of eggs.

If not, the pension only gives you 15 eggs. Do you eat the white today and the yolk tomorrow? This situation greatly harms the poorest families. And that is a responsibility that must be covered. Somehow, our policies have to avoid that.

Let’s imagine that the subsidy is changed. From generalized food subsidies to people’s subsidies. We are going to multiply that pension by three, from 1,500 to 4,500. If the egg is 3,000 pesos, they are going to buy a carton of eggs and half a carton of eggs.

But if the exchange rate rises and reaches 400, the egg will no longer be sold at 3,000…logically that pension becomes salt and water again. The problem is that what these people basically buy are the products that satisfy their vital needs. There are no luxuries there, absolutely none.

In fact, they are people who practically do not have the money to even buy a new pair of shoes. I mean, it’s just eating to survive.

This increase in the rate harms the poor in Cuba the most. That is why speculation must be combated. We must fight it, I say it again, by resuming the functions that the Cuban monetary authority has to exercise over the money market. There is no other option. I emphasize it: it harms everyone. Absolutely everyone. And it has medium-term damage because many businesses stop. And they stop exactly because of the uncertainty that this rate generates, growing without any control and knowing that it is a purely speculative rate, that really behind that rate there are no real purchase and sale operations to support it.

The motto of these months has been “correct distortions and re-boost the economy.” It is not possible to correct any of the distortions if you do not start here.

It is one of the most important distortions, but I would not like to catalog them all here now, putting it on a list as the first, the second, the third, because there are many distortions. In fact, the concept of distortion should be reviewed. The economist Ricardo Torres published a very interesting article in Nueva Sociedad explaining this. One of the most important is this, the exchange rate. It affects the costs of all enterprises.

Also of the sacrosanct state enterprise, which is sacrosanct because the bulk of the national economy depends on it….

80% of the Gross Domestic Product, 92% of sales, more than 1,400,000 employees and lots of families depending on the state enterprise… I emphasize that the state enterprise must be rescued.

The state enterprise is also affected by the devaluation of the peso because Cubans work in the state enterprise, they receive a salary and have to go to a market, to a private enterprise — it’s good that private enterprises exist; I wish there were 20,000 more of them in Cuba — and buy at those prices influenced by the exchange rate.

They are also influenced by high costs, by high taxes, by a 10% tax on total sales. These taxes have allowed a recovery in budget income, but they are costing in this other part of the equation.

That Cuban has to go there when he receives his salary from the state enterprise. And the average salary in Cuba today is not high either.

The greatest incentive that workers have is that they receive a salary for their work and that this salary is at least enough to cover their minimum vital needs and of their family. If it’s not enough for them, there is a huge disincentive.

Of course, and the desire to emigrate from the labor sector begins, the desire to emigrate from the country begins, hopelessness, exhaustion, family breakups…. Everything that is happening to us begins.

Or, simply, the desire begins to not work, to yield less. And therefore, the enterprise becomes more unproductive. If we want the state enterprise to be able to fulfill the role it must play in this country, the distortions must be resolved because they also affect the state enterprise.

In all this time in which we have been seeing how the dollar-peso relationship changed, first downwards, now rising, I have the impression that many people bought the idea that there is a kind of “MSM” conspiracy on one side, or a government conspiracy on the other or conspiracy of those who create the rates, etc. According to what each person wants. But, in all cases, the analysis starts from a vision of the economy broken into pieces, as if one thing had no impact on the other as if the dynamics were not integrated. The inaction of the authorities participates in this speculative loop. This kind of laissez-faire, Adam Smith style…this laissez-faire becomes harmful to everyone. We are on June 6. The possibilities that this year could be a little better, in addition to the issue of the exchange rate, which we already see is very important, what would it depend on?

What remains is six months and it is a short time. I believe that Cuba has three very large and very complex areas of action in which we must act at the same time.

The first is to decide the path of reform, which is a long process, lasting more than 30 years. What is the path of reform? And that decision does not depend on having money, but on political consensus, definitely.

Political consensus?

Politicians, exactly. The economy is the most political thing in the world. Whoever tells you otherwise, is lying to you.

The reform requires political consensus. We had documents that guided the reform until 2017. But from 2018 to now the economy changed. Cuba and the world changed. And those documents, in my opinion, have fallen relatively behind reality. We have to achieve political consensus about the direction of the reform, its breadth, its depth; of the participation of the different actors and the people of Cuba in the reform; of the role of the private and cooperative sector, and the role of the state enterprise in all this. With the necessary real transformation of the state enterprise, which has been a pending issue for 40 years.

In 1984, at the Congress of Economists, a diagnosis of the state enterprise was made that today, 40 years later, is perfectly valid. That document, still written on a yellow sheet of gazette paper, exists. We took that document, at the previous Congress of Economists, and read it. And the diagnosis was practically the same…

We must stop letting the state enterprise be what it should be: an enterprise. And get rid of the fears generated by the enterprise being truly autonomous. Two books would have to be written about how the concept of autonomy has been interpreted in Cuba. And we must decide which enterprises have to be managed by the State.

We have been trying to pass an enterprise law for three years that we continue to postpone. That is a serious problem. The reform goes through there.

Proof that this political consensus is lacking is precisely an enterprise law that remains bogged down.

There is no definition of the most important actor in the Cuban economy. Then you can just imagine.

The other major area is the macroeconomic stabilization program.

We still don’t know what it’s about….

Exactly. That program must be shared, that program must be aired, it must be discussed, goals must be set, dates must be set for that program.

And the third area is that of productive transformation. Because all of this is unsustainable if we do not achieve a deep, clear productive transformation, in line with these times of the national economy. And these three areas are very related.

For some you need money, for others, you don’t need money. And, logically, for the economy to recover, its actors have to have confidence. And that confidence today is very diminished, very affected —both national and international actors.

To have confidence, it’s necessary to come to an agreement with ourselves and find viable formulas to pay the debt, to fulfill the commitments that we have not fulfilled. And that is possible — a lot has been written about it.

To generate trust, it is necessary to facilitate business with foreign investment, not only for state enterprises but also for private enterprises and cooperatives. And that is a regulation that has been around for two and a half, three years, and it has not been finalized either.

The productive transformation goes through that. It involves having an industrial policy. And when I talk about industrial policy, I’m talking not only about industry but also about Cuban agriculture.

When you talk about productive transformation, I understand that it has to do with changing the energy matrix. A change in the matrix towards renewable sources has been promised for decades. And this is something that is taking baby steps, slowly, very calmly.

Time is the most important variable for human beings, for society and for politicians. The most political. The most political variable of all is time.

Yes, you need to change the matrix. Unfortunately, in the planned transformation of the Cuban sugar industry ― and this is the only thing I am going to say about this ― it was agreed to build 12 bioelectric plants that today would be a present for Cuba and for the Cuban population. Unfortunately, only one has been built. From 2004 to today, only one.

This is not to gloat about how bad we are. What I want to say is that they are issues that had been raised and that we must try to recover. Without energy, there is no development.

You can have an increasingly lower energy density because you increase the efficiency of the technologies you use or because you productively transform the country and work more towards some less consuming services. But, without energy, there is no development. Development implies an absolute increase in energy consumption, although good development requires a relative decrease of that consumption per unit of increased gross product.

I don’t have a crystal ball to tell you what’s going to happen in six months. I think we have to drastically change some of the trends that are being expressed today. One of those changes would come exactly by making some type of intervention in the Cuban monetary market, which today, in my opinion, is what most affects the entire Cuban population and the entire Cuban economy.

I continue to believe that Cubans have an enormous capacity, not only to survive but to reinvent themselves every day. Every day I see it. And we must rely on that enormous capacity of the Cubans. You have to give the Cubans confidence, let them do it. And for that, rules are logically needed.

Our country has changed; its structure, its economy, its people, the environment. We have to ask ourselves what are the rules of the game that we need for this economy to advance, for the country to grow, so that the benefit of growth reaches everyone, although it does not reach equally, mind you, but it reaches everyone.

I remember that phrase from Raúl Castro long ago when he said “we will be more unequal but fairer.” Justice requires that it reaches everyone and that these rules of the game prevent inequality from growing so much that it turns into poverty and poverty from turning into destitution. That’s what it’s about.

Well, I’m going to stop right there to make a brief reflection and we’ll say goodbye. I say this not so much as a journalist, but more as a citizen, thinking about the fear of the risk that change entails — all change generates risks, some can be foreseen and others are not foreseeable. But that fear of change cannot be greater than the fear of poverty, loneliness, sadness, helplessness, and hopelessness among people who are our compatriots. Cubans who, within the island and also abroad, suffer from the current economic situation. Therefore, the greatest imperative has to be to achieve the greatest coverage, the greatest protection possible for today’s Cubans. It cannot be that a situation that makes people’s daily lives precarious, that diminishes their capacity to be happy, to have hope, to be able to move forward with an individual, family, or social life project, extends ad infinitum. There are very difficult decisions to face, but the worst of all is immobility.

That’s right.

We’ll talk again in six months.