I started university around 1953.1 I had no ties with anyone, with any organization, I had no antecedents. I was very young and studied in a school run by priests. I sympathized with Orthodoxy,2 but came from the world of my school in Guanabacoa.

My family sympathized with Batista. My friends at school weren’t interested in politics. I was dying to make contact. At a demonstration I met Fructuoso [Rodríguez]. He was my first acquaintance among the revolutionaries.

The University and the group war

During the period after the revolution against Machado, the University [of Havana] suffered greatly, as it became a target for all political groups in the country. That downgraded it to really important levels. A great deal of the people who were involved in student political life looked for a kind of lever, a springboard to have a representative position, after taking advantage of the prestige given by the university tradition.

I think that the 1930-33 revolution, with [Raúl] Roa’s forgiveness, “se fue a bolina” (went downhill), but without it we would not have existed. The social conquests of the 1933 Revolution have not been justly valued. We know it was frustrated, but its seed remained. Within the walls of the university, most of the revolutionary leaders of this country were formed: [Julio Antonio] Mella, [Antonio] Guiteras, Fidel [Castro Ruz].

With the coup d’état [1952], Batista created a qualitatively different situation. He didn’t realize it, but it was a watershed, for better and for worse. Many of these leaders continued during the first years playing the opposition to Batista, doing demagoguery with student demonstrations and with insurrectionary positions.

The situation would start producing definitions. Many people from the so-called “group war” [bonchismo or gangsterism]3—I don’t dare to say that the majority, but a great many— went along with Batista. Very prominent people did it, including some of the smartest guys at the time, like Rolando Masferrer.

In the period from 1953 to 1956 the Federation of University Students (FEU) won the fight against these old habits. It was a very difficult, muddy contest. In such a context, with the best of intentions, you can fall into a swamp and end up as many did in the 1940s, in a group war in the middle of the struggle against Batista.

That was a danger we faced and it was circumvented with incredible intelligence. Representatives of corruption, group war, and politicking were removed from the University. Others pulled themselves out as they were isolated. And it was won without a shot inside the university. I insist: it was not an easy or peaceful fight. It was terrible.

The place of the insurrection

Something that current historians greatly underestimate is the content of the central ideological discussion of that stage. What defined all the debates almost until the fall of Batista were the methods of struggle, rather than the future program.

Until 1956 the leadership of the opposition against Batista was not in the hands of the insurrectionists, nor of the revolutionaries, not even of Fidel Castro. That is a key element of the scene. The insurrectionary position was typical of a minority group. We were isolated even within the oppositionists.

In the assault on the Moncada [1953] there were no old politicians. All the old politicians condemned that action. All the parties condemned it―all, without exception―just as they later condemned the attack on the Presidential Palace [in 1957].4 They treated us as madmen, gangsters, murderers, anarchists, Trotskyists.

The pact that entailed the Mexico Letter [1956] represented a great crisis within the FEU, one of the biggest that we experienced.5 When the communiqué was known, and that it had been signed by the FEU, it was terrible, because we didn’t have the majority in the organization.

Within the University, of the nearly 13,000 students enrolled at the time, not even a third―let’s say―was in favor of the armed struggle, or of the insurrection, or of the revolution.

It’s not that they were in favor of Batista. Batista, really, never had a boom among university students, nor among the Cuban people. I would say that most of the university student body was “apolitical.” They weren’t interested in politics.

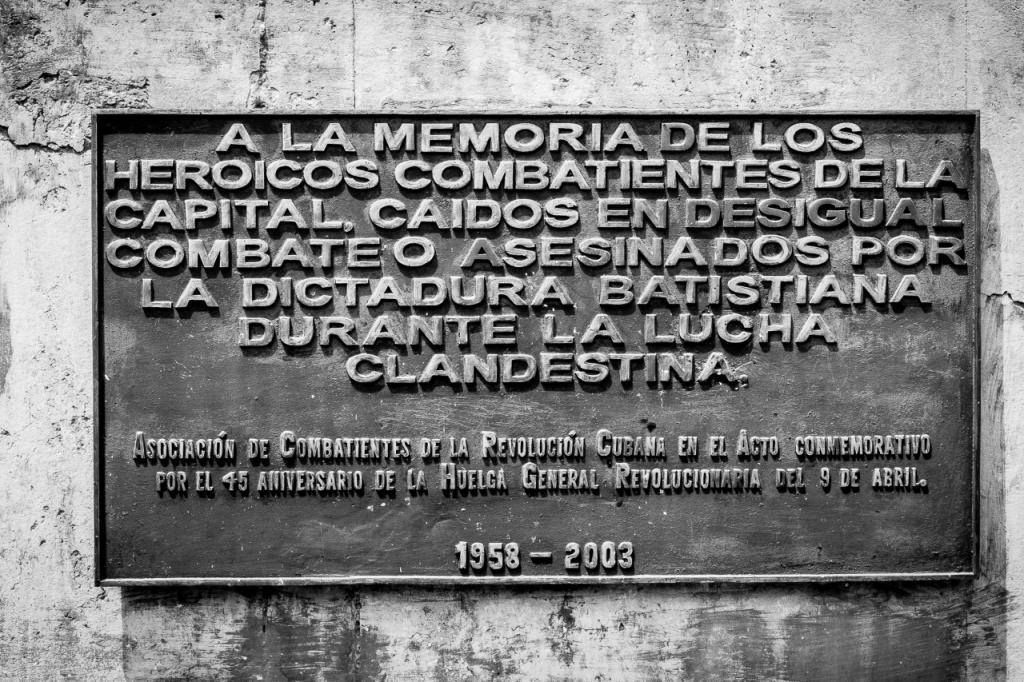

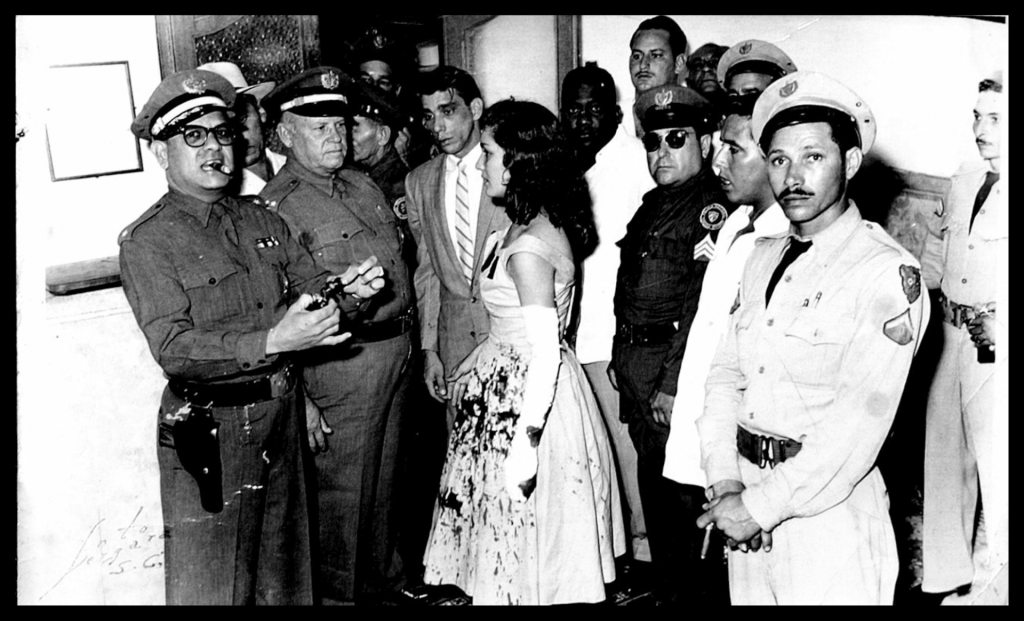

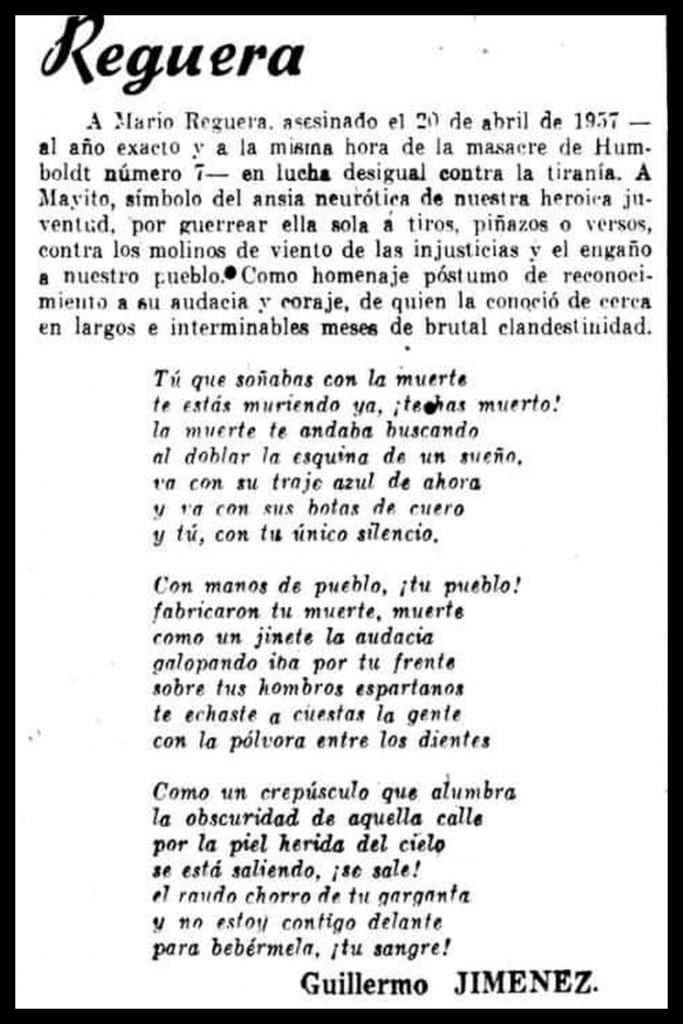

The Trial of Marcos Rodríguez (“Marquitos”)—1964—, Humboldt 7’s informer, made public several of the differences existing between the revolutionary forces since the 1950s. Jiménez had a relevant presence in the trial. The documentary Los amagos de Saturno, by Rosario Alfonso Parodi, dedicated to this topic, has Jiménez as one of its main sources.

Political culture

The situation was one of total frustration among the Cuban people. A heightened cynicism had been created. Skepticism and frustration were common to everyone.

Politics was seen as dirty. People practiced ostrich politics: “I’m not interested in politics, that stains and also does not lead to anything,” “all politicians are the same, they all want the same, they all want to steal, while they are in the opposition they are revolutionaries, when they arrive….”

Those ideas were spread among the six million Cubans at that time, from the illiterate farmer who lived marginalized in a remote area to the screwed-up black man who was in Havana, passing through all social classes, because the bourgeoisie also “quit” politics. After the fall of Machado, the bourgeoisie, as a class, did not get involved in politics. It left it to the political adventurers.

This group explains how the presence of José Antonio [Echeverría] achieved something crucial: to revive hope among a wide series of sectors of the Cuban population through something that always has a tremendous historical effect: being an example.

I want to emphasize something that is forgotten. The police beat us and people said: “look at these idiots, how stupid they are.” We went into battle unarmed. However, the situation was escalating. Although apolitical, many people resented it, and they repudiated the abuse because of human and universal values.

Cubans don’t like abuse. And they didn’t see in us a criminal, a gambler, a pimp, but a student being beaten.

Several could have thought whether those students were wrong, or not, if they were more or less idealistic to the point of fighting with their hands with those violent policemen who beat them, fired shots, hurt people, but it was a vision that made many people reconsider.

The essential role of the FEU, starting with José Antonio, is to fill the void that is being produced in the country, in which the opposition against Batista was still in the hands of the old corrupted politicians, plus other sectors that could well not be corrupt, believed in the possibility of dialogue with Batista.

The University succeeded in bringing the revolutionary student struggle to the streets. It is this tremendous escalade that started creating a state of opinion and awareness everywhere in the country.

Relations between revolutionary organizations

The revolutionary student movement emerged within a combined field of struggle. There was close communication between José Antonio’s FEU and colleagues from all over, including Frank País. Many times with coordination, others without it, but when a revolutionary action occurred on our part or on the part of Santiago [de Cuba], it was immediately supported.

The period that begins on November 27, 1955 and ends in January 1956 with the sugar strike, is one of the highest level in the student struggle. Personally, it is the first and only time in my life that I have seen what is read so much in books, and that has rarely happened in history: that the masses spontaneously launch themselves, without prior organization or direction, to confront the repressive forces on that scale.

The fighting ability of ordinary people, who have never been in combat before, nor has crossed their minds that they are capable of doing so, is incredible once they find themselves in situations of that nature.

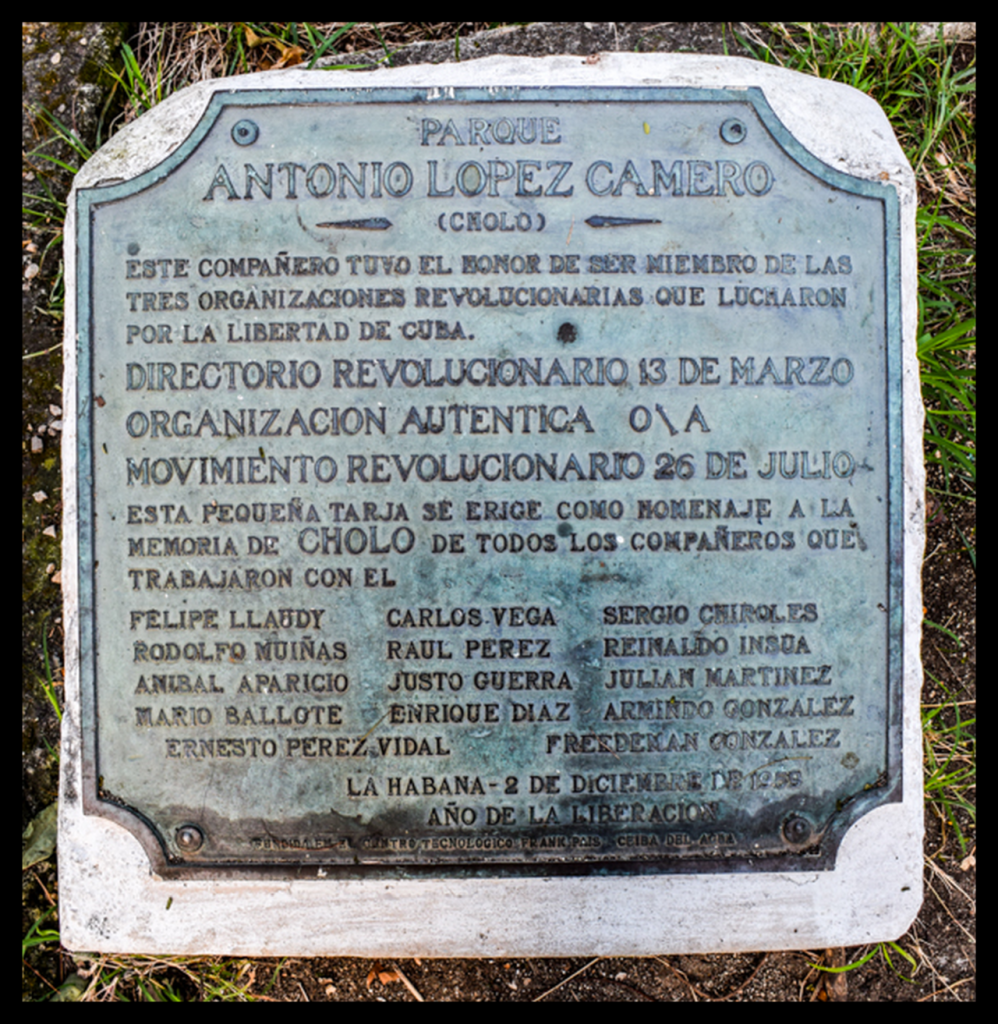

At that time there were no differences that would later exist between the March 13 Revolutionary Directorate (DR) and the July 26 Revolutionary Movement (the 26th).6 The objective was insurrectional struggle, no matter who it was. If there was a colleague who had participated in the Moncada, everyone looked at him with respect.

After the attack on the Palace, the DR is restructured. The persecution is intense, there are no resources, there are no means. In addition, we had the moral weight of the death of José Antonio and the other colleagues. The student struggle had “burned out,” as it was said, most of the DR. They were well-known people, either because of their public participation or because they had been repressed. That was a tremendous backlash for the underground struggle.

During the time that I was in charge of the DR here in Havana, we had meetings with members of the leadership of the 26th. For example, with Marcelo [Fernández Font] at a time when Faustino [Pérez] was in prison. I was also in contact with the heads of action and sabotage and the 26th of July Brigades.

At some point I even made an agreement with the Brigade leadership to work together on a plan of attacks and agitation in Havana. We had a lot of constant mutual collaboration. There were no divisions. I had coordination with Faustino, but not on a personal level, but through intermediaries.7 There came a time when we were all the same.

I see the closure of the University today as a key mistake for the DR. The university was the base, the natural environment of the organization.

When the University was closed, students from other provinces of the country could not stay in Havana, with few exceptions. All those people lost contact with their cell organization. The situation of the underground struggle that was created in Havana after the attack [on Blanco Rico] was horrible for the DR. The persecution of the best-known student leaders was gruesome.

Thus the structure and the contacts were lost. Then those comrades were integrated into what they found in their respective places, mostly into the 26th. Some began to work with them and ended up there as leaders.

In Santa Clara I went to see some of the colleagues who were from the DR, and they were already working as those responsible for things being done by the 26th. A bomb being prepared by Chiqui Gómez Lubián and Quintín’s brother, Julio Pino, exploded. Chiqui and that group were preparing an uprising at that time.

Fructuoso was categorically opposed to reopening the University. There were meetings to discuss the subject, very hot. I saw the matter as he did. How was the matter of the closure of the University end? Well, we said that it could not be opened and there was no one to open it. A great discussion ensued with the university council. If it was a mistake, it was a shared mistake anyway, but we certainly ended up isolating ourselves.

Fidel Castro’s invitation to the DR to go to the Sierra Maestra

There were contacts between Fidel and the DR after the Mexico Pact. Before the attack on the Palace, a month earlier, in February, Fidel sent a letter to José Antonio. At that time, Fidel and the guerrilla fighters were in one of their worst moments. It was not a situation like Alegría de Pío’s, but they were still “taking a breather.”

Fidel’s message consigned, among other things, the need to fulfill the commitments made in the Mexico Letter. The letter impressed José Antonio a lot.8

Already after April [before the Humboldt 7 massacre] Haydee [Santamaría] de la Sierra comes down from the Sierra. Armando [Hart] and Faustino were in prison. I was in Havana. Haydee’s commission was to meet with us to deliver another message from Fidel: that we go to the Sierra to join him. Otherwise, that we send a permanent delegate of the DR to the Sierra.9

Until that moment, the DR’s strategic line, product of the understanding we had about the country and about the real possibilities of the success of the struggle, was to maintain our revolutionary activity in the cities.

We were imbued with the university tradition of the 1930s struggle, which was very important in our formation. We knew people who had participated in actions of the Student Directorate at that time. In the university those things were breathed. There was awareness of their viability. At that time, the dichotomy between the underground struggle, on the one hand, and the guerrilla, on the other, was not raised.

That’s why Fidel’s invitation was not accepted by the DR leadership. I thought then and still believe it was a mistake. After that, there was no regular and official communication between the DR and the Sierra, as there should have been.

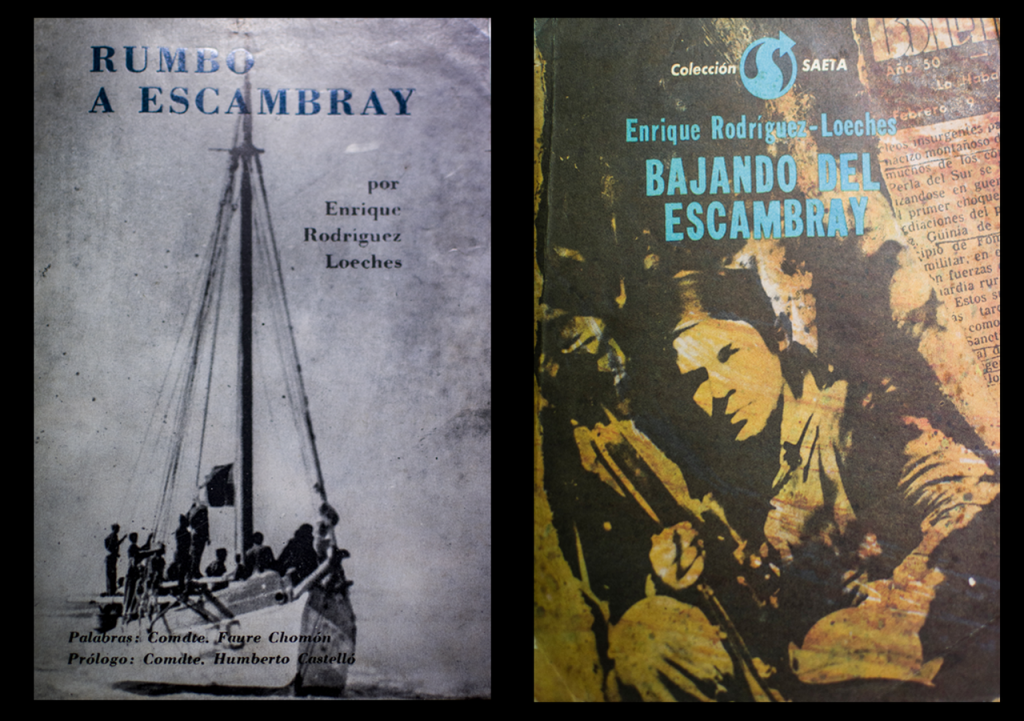

The Escambray Front

I was the one who organized the DR’s Escambray Front.

The DR was almost exterminated. Along the way, I start seeing something that had a great impact on me. I start realizing what Fidel is doing. I begin to see the struggle in the Sierra Maestra not only as a military issue.

The guerrillas provided a means of subsistence, which was important, but they also created an impregnable base to reach the population, a base for permanent political unrest. None of this is possible with the underground struggle. The guerrillas were not isolated, as they demonstrated. In the process, the myth of the guerrilla was forming.

In Havana, the confrontation was increasingly greater. We could not survive. Three-quarters of the time we spent keeping ourselves alive. Without time to think, to strategize.

With much less investment, what we could obtain with the guerrillas would be tremendous politically and militarily. And it would also be for the development of people. It’s possible with guerrilla warfare. The city was totally enemy-occupied terrain.

I conceived and communicated the proposal of the Escambray Front, but it was difficult to process the decisions. People were distributed in many places. Also, while I was in Miami, defending the idea of the Front, we received information about the actions of Eloy [Gutiérrez Menoyo], who was conspiring with Carlos Prío.

Several comrades joined their underestimation of the guerrilla warfare strategy—following what I commented before about the struggle in the cities—with these elements about Eloy. Consequently, they stated that they would not come to the Escambray, but to Havana.

During that period, what would be the April 1958 strike was being prepared. We had obtained a respectable quantity of weapons. Until the last moment the opinion of not coming to the Escambray was maintained. I managed to get Alberto Mora to support me, and with him, others supported me. In short, an eclectic agreement was reached: a group of people would come to Havana and others would stay in the Escambray.

When the time came for the expedition that would bring us, I would leave for Havana, for two reasons. First, because I was the last one who had been to Cuba, and I knew about the organization in all parts of the country. Second, my personal conditions did not allow me to participate in guerrilla warfare: I had four internal operations, had many problems and my condition was still very delicate.

Faure [Chomón], Enrique [Rodríguez Loeches] and Julio [García Oliveras] would come to Havana. In the Escambray, Alberto Mora would remain as coordinator for the national leadership of the DR. As military chief, there was Rolando [Cubela]. Other comrades would also remain there, such as Tavo Machín and [Humberto] Castelló. The weapons were divided: the most suitable for the Escambray and the others for Havana, in preparation for the strike.

We landed the weapons on a small beach in Nuevitas. Except for four or five of us who stayed in a house with the weapons, the rest of the expedition continued to Camagüey. We had a very strong organization in that province. Everything was planned in the area and it worked like clockwork.

On the other hand, the arrival to the Escambray was terrible. The comrades were surprised by the Army. Those of us who came to Havana had the disaster of the occupation of the weapons. We had made a tremendous effort to bring that shipment. We came without food to spend every last kilo on weapons and they took them from us.

The University, and José Antonio Echeverría

I go back, to summarize what I’ve been saying from a broader view.

The University, during the time of José Antonio, truly became the first space for the revolutionaries. I’m not just talking about university students. This is important. This is not spoken of and there’s great confusion. The University was a political, revolutionary and cultural trench for a whole sector of the Cuban population. That was a very heterogeneous group, made up of everyone who had hopes of change, without knowing how or where to get there.

The starting point was the imperative need to change the course of Cuban politics, which had been a disaster since independence. The University was a refuge for the best of the Cuban nation. The University of José Antonio was not only the site of fabulous political demonstrations. It was also a cultural stronghold. Everyone who opposed Batista, but also those who clashed with the system, went to university.

The University was a kind of separate republic. Autonomy was its key. Batista was a very complex ruler. He was no fool. His figure is unprecedented among the dictators of the 1950s in Latin America. He was superior in that sense, more cultured and cunning, with great skill in the use of all political tools.

Batista respected autonomy, which he broke on two or three occasions. This is why the university was a kind of free zone. I acquired a great personal experience, very multifaceted, in such a medium. I was lucky to enter at that time.

The role that Cuban students played during the 20th century in national politics and history is, I believe, unparalleled in Latin America. Of course, on the continent there are important student movements, beginning with the reform of Córdoba [Argentina, in 1918], but they are of a different nature.

I’ve read here in school textbooks that when Batista gave the coup, “backed by the American embassy, all sectors rose up, the political parties, the unions.” I remember that my son, when reading this in school, asked me a question that I have never forgotten: if all these people were against it, why was Batista able to carry out the coup? The question is obvious.

Unfortunately, the discourse of the revolution in power has stigmatized a series of key ideas about those groups and individuals, which have then been simply repeated.

The sweet, rosy image that at the university we were all revolutionaries and that all the people of Cuba were against Batista is a very harmful version for the understanding of the history of this country.

***

Notes:

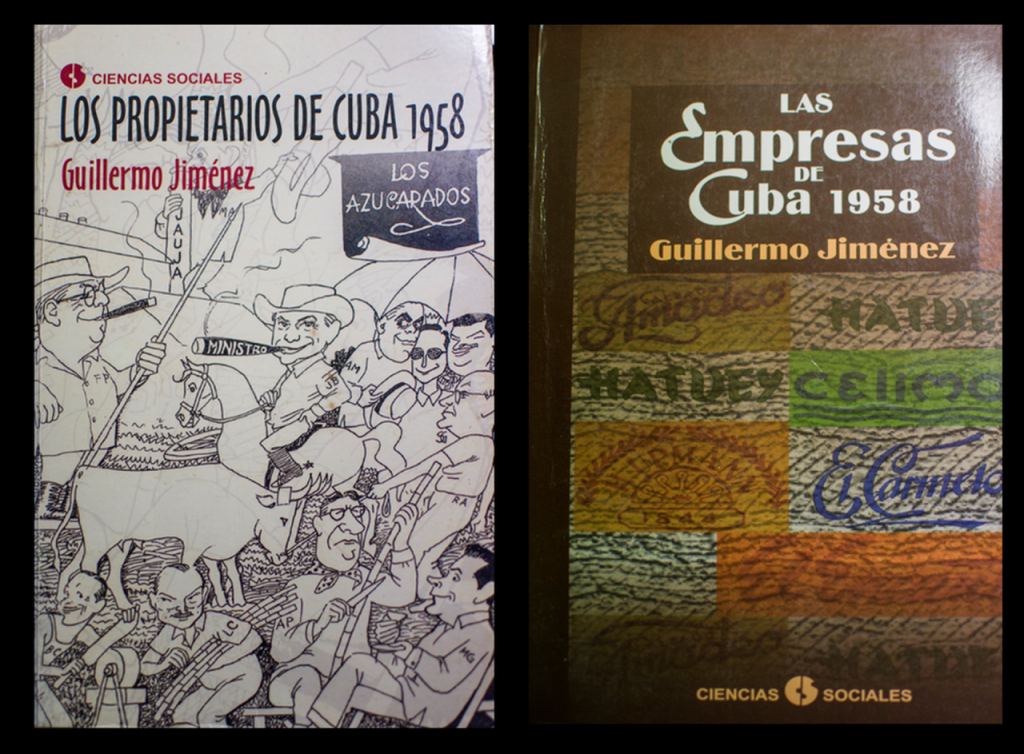

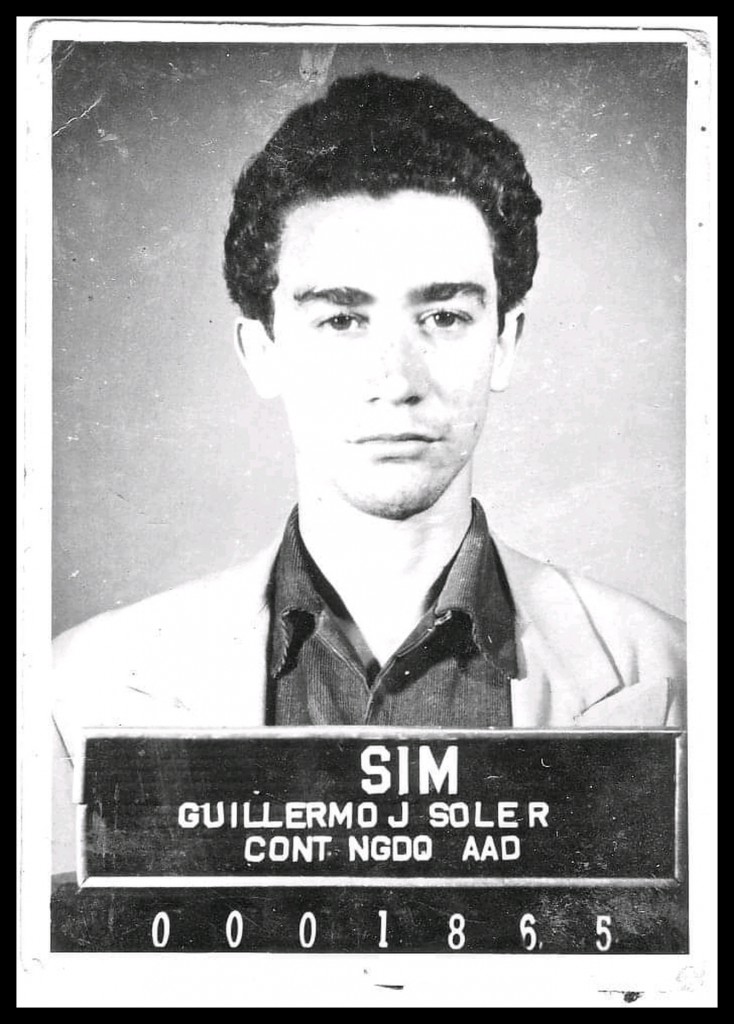

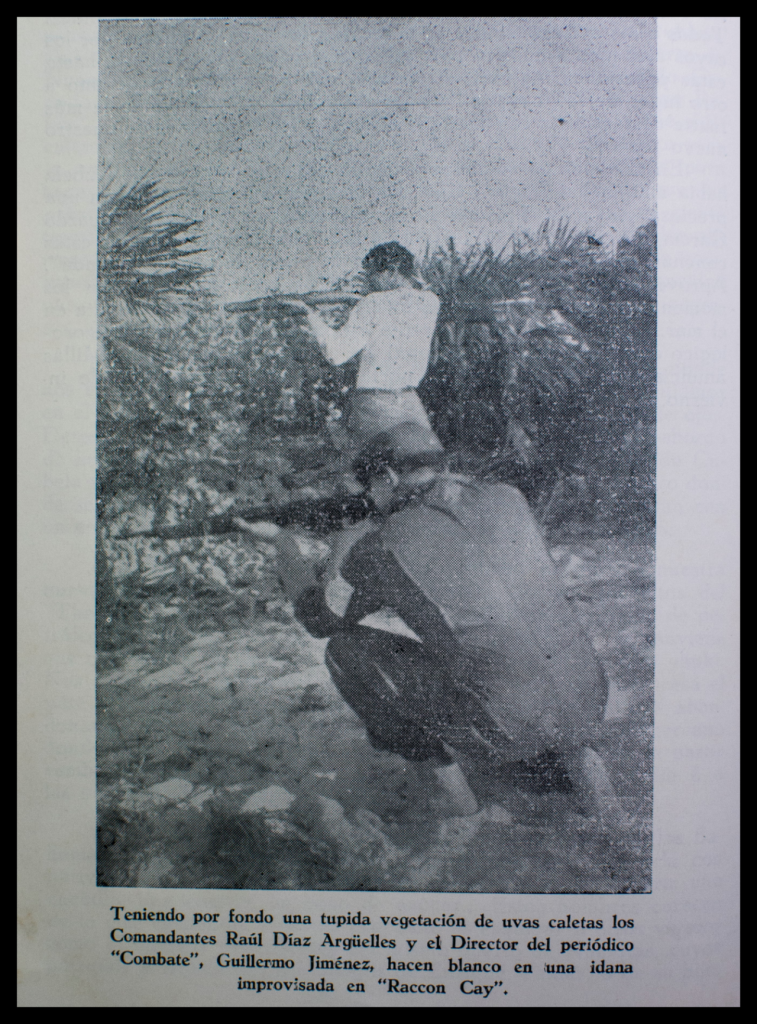

1 Guillermo Jiménez Soler (“Jimenito”) was born on August 22, 1936. He graduated in Law and History from the University of Havana. He began, but did not finish, studies at the Manuel Márquez Sterling School of Journalism. He was a prominent member of the Cuban insurrection against Fulgencio Batista and one of the leaders of the March 13 Revolutionary Directorate. He was deputy editor of the Alma Mater magazine. He arrested several times. In 1956 he was seriously injured in a confrontation with the police. After 1959, he was Commander of the Rebel Army, a member of MINFAR and MININT, directed the Combate newspaper, held executive positions in MINREX, MININT, Banco Nacional de Cuba, managed a factory in the Furniture and Containers Enterprise and another in the Soap and Perfumery Enterprise for more than 10 years. He developed an important historiographical work with Las empresas de Cuba 1958 and Los propietarios de Cuba 1958, which he conceived as a study of Cuban capitalism.

The coverage of his death (May 8, 2020) in official Cuban media generated another of the debates in which his life was involved, marked by the reasoned and unwavering defense of the role of the March 13 Revolutionary Directorate in Cuban history and the memory of his comrades-in-arms.

This testimony is a brief fragment made from a set of interviews that I conducted with Guillermo Jiménez, and a large number of DR members, in the first decade of the 2000s. Aware of the necessary ethics when publishing testimonies of people who have already died, I have exclusively used in this text passages that Jiménez authorized to use and I have added some notes with quotes from other protagonists that confirm his words on controversial points.

2 Name by which the Cuban People’s Party is known, founded by Eduardo Chibás.

3 This is an explanation of the “bonche”: “Inside the University a degenerative process devastated it and overshadowed it. Emerged from the struggles against the dictatorships of Machado and Batista as the emblematic institution of purity of ideals and defense of democracy, constitutional precepts, public honesty and the interests of the people and the nation, it was the object of spurious group interests. In 1940 the so-called university bonche appeared, whose members, with the use of pistols, threatened teachers and students, obtained grades, sought public wages without working, popularly called “botellas,” and carried out acts of vandalism.” El patrimonio cultural de la Universidad de La Habana; coords. Claudia Felipe and José Antonio Baujín. Havana: Editorial UH, 2014, p. 51.

4 On the position of the moderate reformist arch in relation to the Fulgencio Batista regime, Jorge Renato Ibarra Guitart has several investigations. On the position, in particular, of the PSP (Communist Party) in relation to the armed struggle in the 1950s, see texts by Caridad Massón Sena and Gladys Marel García Pérez.

5 A substantive treatment about the Mexico Letter in particular, and the DR in general, is the doctoral thesis of Frank Josúe Solar Cabrales (2016), later reworked as a book (2019).

6 When I conducted the series of interviews that serve as the basis for this text, a letter from Fidel Castro to Ernesto Che Guevara about DR had not yet appeared published (2010), which decisively contributed to making these differences public. Researcher Frank Josué Cabrales has described the publication of this document as a “low intensity earthquake” that “shook the foundations of the historiography on the Cuban Revolution.”

7 Mario Mencía collected Faustino Pérez’s testimony regarding his contacts with the DR leadership in Havana: “They looked anguished, desperate to carry out decisive armed actions.… We talked about the possibility of opening a guerrilla front in the Escambray, but the decision to attack the Palace prevailed…, a plan that they had well advanced.” Mario Mencía: “La Carta de México,” Bohemia magazine, Havana, September 17, 1976, p. 93.

8 Julio García Oliveras comments on the content of this letter, which led José Antonio Echeverría to ask “that we accelerate the preparations to carry out the agreed plan” [attack on the Palace], in Contra Batista, Ciencias Sociales, 2006, La Habana, pp . 311-312.

9 The existence and content of this letter is in turn confirmed by testimonies from Ricardo Alarcón de Quesada and Enrique Rodríguez Loeches.