Read the first part of this article.

The sensation that people under 40 have, that a great many of their friends have left, was that of those who are in their 50s when the rafters crisis suddenly reopened the exodus, at the apex of the Special Period; and even earlier, when those in their 60s, in the upsurge in prosperity in 1980, saw their friends unexpectedly cross to the other side; not to mention those who, on the way or already in their 80s, saw their classmates or playmates leave in the wave of the epic and not always prodigious 1960s.

The Mariel thunderstorm, whose round anniversary is approaching, rumbled under a seemingly clear sky. Its cause cannot be attributed to a formidable political conflict with a civil war and international isolation included (as in the 1960s), or to a collapse of the economy (like 14 years later). It took place in the midst of economic growth, stability and the international thaw of the 1970s, although at a juncture of worsening tensions with the United States.

It is often said that it was the expectations that were opened by the dialogue with the emigration, and the consumerism incited by the 130,000 “community members” who visited the island with the opening, which led to Mariel. Certainly, that change made the possibility of leaving palpable, with a return that had remained closed until then, and doing so loaded with videocassette players and jars of M&M’s for the family. So, why not do it?

Although this hypothesis is consistent with the circumstances, “visits” were only one factor, and perhaps only a trigger. Other variables concurred in Mariel.

The first was that, by terminating the immigration agreement in 1973, the U.S. government had closed the door, leaving many Cubans without a direct exit route. Whenever something similar happened, in 1962, in 1973 and in 1984 (when a bad agreement was reached, later implemented by drops), the result would cause a migratory accumulation.

The second variable was the unexpected, vertiginous and emotional situation, triggered by the events of the Peruvian embassy, and its rapid escalation. Many who had never thought, or had not seriously considered leaving, suddenly faced the option of doing so: “your cousin tells says that if you want to leave, you have a seat in a boat that is waiting for you right now; you have three hours to decide.” The emotional contagion that sociologists study had triggered the massive entry into the Peruvian embassy and accelerated the Mariel spiral, which facilitated equally intense adverse reactions.

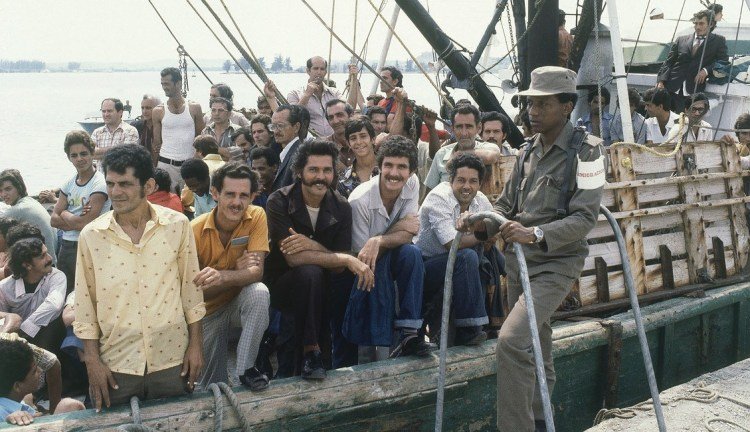

As a whole, those who left through Mariel looked more like Cuban society than any previous emigration. Among them there were no longer large land or property owners or upper middle class, and although the proportion of professionals and farmers was much lower than that of the country, and that of the unemployed reached almost a quarter of the total flow, 3 out of 5 were workers. The proportion of blacks and mestizos and single men was much higher than all previous flows; almost half had no relatives in the United States; and the vast majority did not speak English. Naturally, their socio-economic and cultural profile, and their education and appearance were not those of the historical exile, the one which rejected them because “they didn’t look like Cubans,” and disparagingly called them Marielitos. Although only 15% of them had a criminal record, in Cuba they were simply called scum. [1]

For the issue at hand, this double rejection suffered by Mariel migrants left an indelible mark. The acrimony of the acts of repudiation, later multiplied in the mirror of literature, theater and cinema, prevails in memory, beyond other dimensions of that intense episode. On this side, however, for many young revolutionary Cubans, the marches in front of the Peruvian embassy, prologue of Mariel, were then lived as their first real political experience.

The government of Peru had lent itself to an operation managed from Washington, by those who in the Carter administration had struggled from the beginning against the rapprochement.

The trauma of Mariel would contradictorily feed the culture of exile. I met a couple of humble workers who left through the Peruvian embassy, and still live in a working-class neighborhood in Lima. He told me that he would never return to Cuba again. She visits frequently, organizes groups of Cuban emigrants and even collaborates with the Cuban embassy. The two have their reasons.

In the end, research shows that, with Mariel, a new stage of Cuban emigration began, characterized by the permanent link with Cuban society. It is they, who left since 1980, who fueled most of the flights and remittances in later years, especially since the crisis of the 1990s.

The Special Period rafters would not be bid farewell with acts of repudiation, but with gestures of solidarity and fraternity, hugs and prayers. Cuban society had changed; and so had politics. Henceforth, emigration was going to increasingly mean part of a family survival strategy. Following that logic, they would never stop looking back or break away from their previous life―even when they still didn’t have the help of Facebook or WhatsApp, or commercial airlines’ regular flights.

However, those who emigrated until January 2013, no matter if it was because of the economic situation or family reunification, continued to fall into the black hole of exile, because they lost their permanent residence in Cuba, along with their other citizenship rights. This was the prevailing condition, even if they had not really started off as exiles.

For example, most of the intellectuals and artists who left in the 1990s, and decided to stay “definitively,” instead of opting for the privilege granted to the guild and other professionals (through the institutions where they worked or those they were linked to), to acquire a PRE (residence permit abroad), they chose to let the door close behind them. Almost none could have documented that their departure responded to fear of repression for political or religious reasons which, according to the UN, endorses the category of refugee.

Most of them processed their exit permit: for a scholarship; for a work stay; for a stay for personal reasons (visiting relatives, marriage with a foreigner). Even those who applied for an immigrant visa for the United States or Europe or any other place, or received it unexpectedly, because their spouse or family member had suddenly won “the bombo” (an American immigrant visa obtained by lottery) were not considered political refugees in those countries, under no circumstances. So how the hell did they become “exiles”?

The self-perception of Cubans and their true national pride are no strangers to this attitude. To the extent that the condition of exile circumvents economic or family reasons, identifying themselves as a simple immigrant brings them closer to Mexicans, Central Americans, Dominicans, Jamaicans, Peruvians, Ecuadorians―often rabble. On the other hand, it also implies having a neutral position with respect to Cuban politics. Both attitudes are strange to a predominant cultural code in Cuban emigration, which reneges being “Hispanic” or “Latino” in the United States; “Sudaca” in Spain; or “Caribbean” in the rest of Europe. None of that responds to anti-Castroism, ideological or cultural, but to feeling different. The other Latin American and Caribbean people realize this.

On the other hand, under the apparently coherent umbrella of a predominant anti-Castro culture there exists a very varied whole. This heterogeneity does not respond only to the successive waves and their very different social groups, values and political interests; but to the nature of the “glue” that binds them.

In a strictly ideological and intellectual sense, the culture of anti-Castroism lacks an organic management center. The exile organizations have always been diverse, from former Batista followers and Rebel Army guerrillas, to Communist Party members and Rapid Response Brigade leaders turned opponents.

None of them are usually headed by organic intellectuals. Those who in emigration adopted the condition of exiles and work as academicians, writers or journalists, usually don’t direct any of them. The years in which professors Enrique Baloyra and José Ignacio Rasco, and journalist and editorial businessman Carlos Alberto Montaner, represented that Democratic Platform, where three of the many organizations in exile joined, are a thing of the past.

After this quick overview of such an intricate problem, what is the nature of classical anti-Castroism? Is it an “ideology,” that of historical exile? Or rather a psychological charge made up of resentment, cystic fury, catharsis in the face of helplessness and grief over what is left behind and lost―as a friend of mine says―for “the shame of having been and the pain of no longer being”?

Whatever the answer to these questions, there is still the question of how that feeling is reproduced today within a very mixed population due to the successive migration waves, whose majority did not lose property, nor a privileged way of life, since more than half arrived after the crisis of the 1990s.

Could it be because that way they find the key to their assimilation of the environment? Or does it also respond, as others suggest, to their personal frustrations regarding the dynamics on the island, to another grudge against a past that is still there, without change or visible solution, as they continue seeing on the networks, through the eyes of their friends on Facebook who remain here?

Paraphrasing Marial Iglesias, will it be a pattern that reproduces “the metaphors of no change,” there and here?

It is not possible to fully address these issues without delving into the nature of the real changes, including behaviors and ways of thinking, on both sides.

Note:

[1] Rafael Hernández and Redi Gómis. “Retrato del Mariel: el ángulo socioeconómico” (Cuadernos de Nuestra América, # 5, January-July 1986.)

Read the first part of this article.