Do you remember the new Cuban economy with greater cooperative participation that was promised as part of the “updating” that began more than a decade ago? The main documents leading this reform process, the Guidelines and Conceptualization, and the new 2019 Constitution, establish that cooperatives should be the second most important business form after state-owned enterprises, that they should contribute to solving local problems and that they should receive special attention from the State.

Well, instead of the consolidation and expansion of the Cuban cooperative sector, what we have seen is a decline in the total number of cooperatives and their members or associates (“partners”). The cooperative fad passed quickly: just a couple of years. In fact, the word “cooperatives” seems to have almost disappeared from the vocabulary of public officials, and even from the official media.

How are Cuban cooperatives doing more than a decade after the promise of a more social and solidarity-based economy? What explains this current situation in which cooperatives seem to have disappeared from public policies and even from the discourse of public officials, and private companies receive more government attention and a more favorable (or less unfavorable) environment than cooperatives? Could it be that the pause for cooperatives will never end?

Evolution over last decade

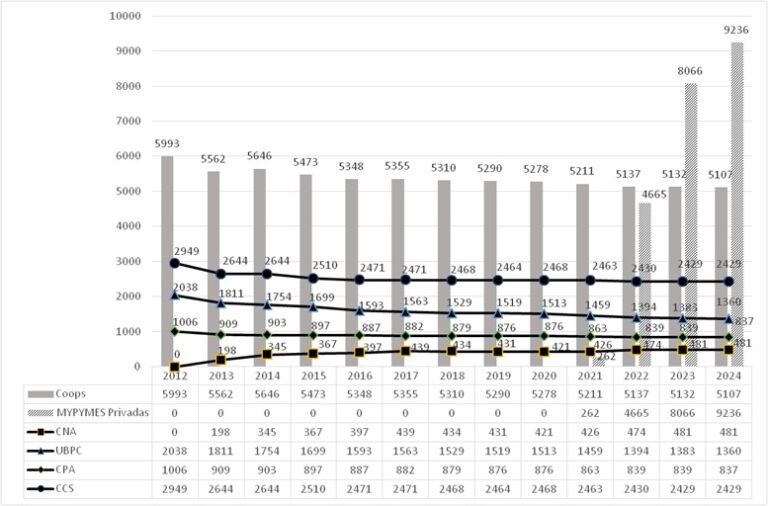

According to the National Office of Statistics and Information (ONEI), at the end of 2024 there were 5,107 cooperatives in Cuba, of which 481 were non-agricultural cooperatives (CNA) and the rest (4,626) were agricultural: 2,429 CCS, 837 CPA, and 1,360 UBPC.1

As can be seen in Chart 1, this represents a net decrease compared to 2023, with 25 fewer cooperatives, due to a reduction in agricultural cooperatives, almost all of them UBPCs, while the total number of CNAs remained the same.

Chart 1. Cuban non-state enterprises, by type of ownership (2012-2024)

Most alarming is that the number of agricultural cooperatives has decreased at a much faster rate than in previous decades. While until 2011, an average of 24 UBPCs and 3 CPAs were dissolved annually, between 2012 and 2024 these figures increased to more than 60 UBPCs and 15 CPAs dissolved annually.

Thus, by the end of 2024, there were a total of 1,367 fewer agricultural cooperatives, equivalent to 77% of the number in 2012: 67%, 83% and 82% of UBPCs, CCSs and CPAs, respectively. It is important to note that, unlike in previous decades, when the number of CCSs fluctuated slightly, they have also decreased in the last decade.2

Regarding CNAs, a growth of more than 400 was recorded between 2012 and 2017. This growth, compared to other countries and considering the experimental nature of the legislation and the limited two-year approval period, was impressive.

Before the approval of the new regulations at the end of 2020, around 439 CNAs had been created, of which 421 still existed at the end of 2020; meaning that only 18 were dissolved after 3 to 5 years.

Since then, a net growth of only 60 CNAs has been recorded, evidencing a considerable slowdown in their growth and suggesting that other CNAs have been dissolved, some due to their conversion to private MSMEs, while others have not survived all the shocks analyzed below.

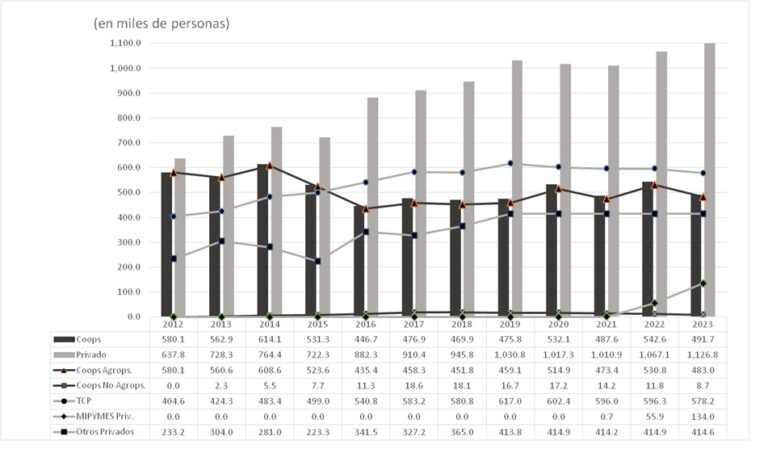

Chart 2 shows that cooperative membership has decreased by 88,400 people from 2012 to 2023, representing 85% at that time. Within the non-state sector, the private sector has achieved a greater share of productive employment (26.2%) than the cooperative sector (11.4%), with all the economic, social and cultural implications this entails.

Chart 2. Non-state employment in Cuba, by type of company (2012-2023; in thousands of people)

Main shocks and challenges

During the last decade, a “perfect storm” has occurred, affecting even those Cuban cooperatives with solid governance and efficient business management. They have faced enormous challenges resulting from an unfavorable legal environment and a series of national and international external shocks:

- Redistribution of idle lands, which prioritized private farmers over cooperatives.

- Barriers to cooperatives developing their own supply and marketing channels and meeting the needs of their members.

- Impediment — until recently — to creating second-level cooperatives.

- Reorganization Task, which unleashed hyperinflation, de facto dollarization and recentralization, and affected cooperatives the most due to their closer ties (for purchases, sales and rentals of premises) with state-owned enterprises and their greater transparency.

- Regulatory changes that imposed severe limits on their operations and even their management autonomy nullified the advantages cooperatives had enjoyed in terms of so-called “preferential treatment” and opened the door to demutualization.

- Absence of public policy, legislation and institutional framework necessary for the development of cooperatives.

Redistribution of idle land

A major shock that agricultural cooperatives have suffered since the beginning of the last decade has been the redistribution of idle land policy initiated in 2008, which has prioritized private farmers (individual or family) over cooperatives.

This encouraged cooperative members to abandon them to obtain their own land and better incomes. At the same time, it particularly weakened the CCSs, as they were overwhelmed with the obligation to train and provide services to new beneficiaries, even if they were not members.

Between 2007 and 2018, management of 20% of agricultural land was transferred from cooperatives, primarily UBPCs, to private farmers, while the amount of land under state management remained almost unchanged.

While it was absolutely necessary to put idle land to work, the design and implementation of this measure reflected a contradictory policy shift toward agricultural cooperatives.

It revealed the abandonment of decades of recognition of the cooperative model as the best ally of the individual or family farmer, and a lack of knowledge about the central role that cooperatives have historically played, not only in the nation’s food security, but also in the economic, social and cultural development of rural communities.

Access to inputs

The redistribution of land into more private hands has increased pressure on inputs (seeds, fertilizers, fuel, etc.) and services (plowing, harvesting, transportation, etc.), controlled by state monopolies, and has reduced cooperatives’ access to them.

In recent years, this shortage of agricultural inputs has been critical: agricultural cooperatives currently have access, at best, to 30% of the inputs they had in 2019.

For both agricultural and non-agricultural cooperatives, barriers persist to their developing their own supply and marketing channels and meeting the needs of their members.

While the private sector has been able to be “creative” in its provisioning and it has even publicly acknowledged its access to the black market, cooperatives face limitations in creating accounts in freely convertible currency (MLC), importing and exporting, and are unable to fund their MLC accounts except through exports.

Even when they can export and earn foreign currency (MLC), they cannot use it because the state-owned importing enterprises that sell them in MLC lack supplies.

Second-level cooperatives

Until recently, agricultural cooperatives have been prevented from creating second-level cooperatives.

It is inexplicable that the promotion of these cooperatives of cooperatives, which would solve supply problems and many others, and which have demonstrated their validity and great potential internationally, is not at the center of efforts to increase agricultural production.

Reorganization Task

Cooperatives, like all Cuban business forms, were hit hard starting in 2020 by the so-called Reorganization Task, as it generated hyperinflation and de facto dollarization, accompanied by greater recentralization in the state sector.

But the Reorganization Task had three additional blows that affected cooperatives much more severely, due to their closer ties to — or dependence on — state-owned enterprises for their supplies, sales and rental of premises.

The prices of inputs purchased from state-owned enterprises multiplied, exceeding what the cooperatives could charge for their products.

Many of the cooperatives’ clients were state-owned enterprises or institutions, which set disproportionately low prices, halted their purchases for many months and subsequently made downward adjustments.

The CNAs also suffered disproportionate increases in rents for state-owned premises and operational restrictions associated with the Reorganization Task.

Hyperinflation and the need for foreign currency to access inputs further limited the cooperatives. Unlike private ventures, the governance of cooperatives prevents them from operating effectively in the informal market for dollars and productive inputs.

It is more difficult for cooperatives to access the black market because they must be transparent with their members, and one secret among many is no longer a secret.

Regulatory changes

On the other hand, the regulatory changes of 2018-19 and 2023 (for agricultural co-ops) and of 2019, 2021 and 2024 (for non-agricultural co-ops), while included some steps forward, have resulted in three impacts for cooperatives.

On the one hand, especially those of 2018-19, they imposed some serious limits on their operations and even on their management autonomy, which have only been partially overcome.4

The most recent regulations finally recognized cooperative autonomy, but at the same time — under the new (neoliberal) dogma of “level playing field for all enterprises” — they nullified the advantages that cooperatives had in terms of so-called “preferential treatment.”5

Currently, these advantages have been reduced to a lower tax burden, which, in practice, has also been nullified by the effects of the Reorganization Task and the operational barriers already analyzed.

Furthermore, these regulations opened the door to the demutualization or conversion of cooperatives to MSMEs, while not even mentioning how an MSME that reaches the maximum of 100 employees could be converted into a CNA.

Cooperatives converted to private MSMEs: urgent need to correct regulations

No public promotion policy

Finally, but no less important, cooperatives have been affected by the lamentable ongoing absence of a public policy to promote cooperatives, of legislation that unifies and undoes obstacles for all types of cooperatives , and of specialized institutions that truly understand and take advantage of the specificities of the cooperative model.

To have a healthy cooperative sector, it is essential to have institutions that fulfill the necessary basic functions of promotion, representation and pedagogical supervision; not to mention the need for coordination of public policies, financing, education, research and development.

All the crises

Although it may seem obvious, it should not be overlooked that, starting in 2019, cooperatives — like all Cuban business forms — have been affected by a severe national economic crisis.

It would be dishonest to fail to recognize that this crisis has largely resulted from the tightening of the blockade and the economic war waged by the Trump and Biden administrations, which have managed to strangle the country’s main sources of foreign currency: tourism, medical missions and remittances.

Obviously, the COVID-19 pandemic further devastated an economy largely dependent on tourism, and which spared no expense in developing vaccines and implementing vaccination campaigns.

But it must also be recognized that the current crisis is partly a product of the failure of the reforms implemented in the last decade to achieve the expected results.

Among these failures, although not given the importance it deserves, is the failure to support the cooperative sector.

Doing nothing has been a serious mistake

The decline of the Cuban cooperative sector has been the result of serious mistakes that have been made and continue to be made in the promotion and development of cooperatives. We continue to be one of the very few countries in the region that does not have a general law for all types of cooperatives, despite having announced it more than a decade ago.

We don’t have to wait for a cooperative law, nor for the long-awaited foreign exchange market, to lift the many operational barriers that cooperatives face every day, which in many cases depend on nothing more than at least letting them operate.

A pause that never ends?

The experiment with non-agricultural cooperatives in Cuba was officially suspended in 2016; de facto since 2015, when the State stopped hiring them and increased their taxes.

The government’s justification, based on an evaluation presented in 2017, cited deviations from the original objective, lack of control, a tendency toward rising prices and misuse of credits.

It is significant that most of these problems were institutional failures external to the cooperatives — such as inadequate oversight and opacity in government contracting processes — although the responsibility fell on them.

Despite acknowledging that the problematic cases were in the minority and concentrated in specific sectors such as construction, the response was not to strengthen the model, but to halt it indefinitely.

With the private sector, there was no such punishment; quite the opposite. The simultaneous evaluation of self-employment detected more serious and widespread irregularities, such as tax evasion and covert hiring of workers.

However, in that case, the solutions focused on better oversight and training, with only a brief halt in the issuance of licenses.

As demonstrated by the evolution of the number and membership of Cuban cooperatives over the last 12 years and the analysis of the factors behind this decline discussed here, the pause for cooperatives decreed a decade ago still persists and has become an abandonment of the model in public policy, both in regulations and in practice.

If a group proposes the creation of a cooperative, it is not unusual to be asked why they don’t create an MSME. There are no known conversions of state-owned enterprise units to cooperative management after 2015.

Cooperatives have been hindered from renting state-owned premises, openly favoring the private sector. Many of the CNAs that rent premises have been subject to disproportionately high prices.

Agricultural cooperatives appear to have no support, either central or local, to address their lack of basic inputs for food production. Local governments in rural areas, with several cooperatives interested in joining, do not appear to have facilitated the emergence of even a single second-level cooperative.

All of this demonstrates a clear preference among public officials for other non-state forms of cooperatives, such as private MSMEs, self-employment and private agricultural producers.

Could it be that it has been decided that cooperatives are no longer useful for Cuba’s new development model, and we haven’t realized it?

________________________________________

Notes:

- The different types of cooperatives in Cuba are: 1) Credit and Service Cooperatives (CCS, which are cooperatives of private farmers and producers) since 1960; 2) Agricultural Production Cooperatives (CPA, which are cooperatives of farmers and administrative staff workers) since 1975; 3) Basic Agricultural Production Units (UBPC, which are cooperatives of farmers and administrative staff workers who lease state lands for free usufruct) since 1993; and 4) Non-Agricultural Cooperatives (CNAs; which are generally worker cooperatives, but could also be producer cooperatives, in any case, in activities other than agriculture) since 2013.

- The reduction in the number of agricultural cooperatives and their members is a global trend due primarily to consolidation (mergers of cooperatives) and the decline in the number of farmers as a result of migration to urban areas and the reduction in agricultural activity. In Cuba, other factors have also played a role and are analyzed below.

- The ONEI has not yet published employment data as of the end of 2024.

- In particular, Decree-Law 366 of 2019 established that CNAs could not market outside the province where they were registered, limited their membership growth to less than 10% of their size at the time the regulation was passed, and restricted — as mentioned above — their access to bank accounts that would allow them to operate in existing currencies (CUC at the time, MLC after the regulation), their sales to state-owned enterprises and the ability of exporting cooperatives to hold foreign currency accounts. Decree-Law 365/2018, for agricultural cooperatives, finally unified their regulations but continued to limit their adherence to cooperative principles.

- The CNAs initially had a grace period for paying taxes, priority access to sales of state inputs, rental of state-owned premises and banking credit and services, and preference as a model for converting state-owned business units to non-state management.

________________________________________

Sources for the preparation of the graphs:

- “Empleo y Salarios” (Employment and Wages) in Statistical Yearbook of Cuba 2023, ONEI, 2024.

- “Organización Institucional. Principales Entidades. Marzo de 2025” (Institutional Organization. Main Entities. March 2025), ONEI, 2025.