by Lívia Magalhães

We Brazilians are many things: the country of carnival and, of course, of soccer. We are the country of the King, of the greatest soccer player of all time. But we are also a racist country, deeply racist.

At first glance, it seems contradictory if we recognize that our greatest idol was a poor, black player, in a conservative and elitist space like Brazilian soccer for a long time. The trauma of the Maracanazo, the defeat against Uruguay in the 1950 World Cup final, was much more than a sports drama: it was shown as an “opportunity” to reinforce our racism.

The “fault,” many said, lay with the black players, unable to compete because of their racial “weaknesses.” It is a discourse that is constantly reinvented in the country and is not restricted to sports. Four years ago an openly racist president was elected in Brazil who, luckily, in a few hours will leave, ashamed, the presidency; but it reflects much of our society.

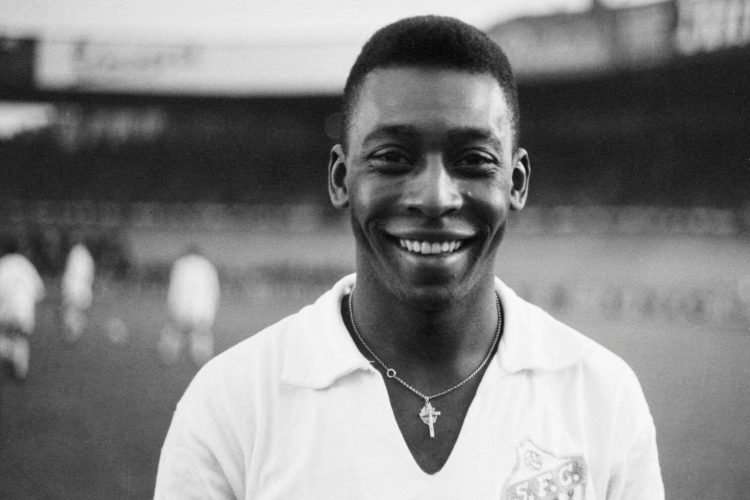

Brazil was the last country in the Americas to abolish slavery, in 1888. A year later, we proclaimed ourselves a Republic, with a modernizing promise that was exclusive and disinterested in combating its racism. We formed ourselves as a republic based on a violently racist structure. In this scenario, half a century after the end of slavery, our black King, Edson Arantes do Nascimento, arrived.

Pelé was born under a dictatorship, the Estado Novo of Getúlio Vargas. Among his national projects, power used both soccer and the myth of racial democracy. It was the intellectual invention disseminated from the national State of a country that, according to the official discourse, was recognized through the union of three races: the native indigenous, the European white and the African black. The romanticization of the violence of the conquest was the basis of the construction of nationality and created roots that remain firm to this day.

In 1958, shortly after the drama of 1950, it was the black boy, who was not yet king, only 17 years old, who shone in Sweden as a fundamental part of the team that won the first World Cup for Brazil. In twelve years, or four World Cups, Pelé managed to bring home three cups. In addition, he became the great star of world sports, recognized and acclaimed throughout the globe. How could it be otherwise, his fame and recognition were a resource for a racist country to reinforce its false racial democracy.

https://youtu.be/3A3YbP9_Ty8

Pelé was valued and recognized in Brazil, and today there are many tributes. But throughout his career and his public life, there were also many criticisms and demands. That is where the racial rule shows itself strong. Like everyone, Pelé made mistakes; but there is no doubt that his were more questioned than those of other white idols. It is interesting to think about the comparison with another world soccer star, Diego Armando Maradona.

Although rivalries are of interest both to forge national feelings and to generate profits in the capitalist universe, it is important to think about the case of Pelé and Maradona from a racial point of view. I’m not saying that we Brazilians contest Pelé’s sporting superiority. No, that never. But when we think about the human being, about Edson and Diego, one can see how we measure in very different ways.

In Brazil Pelé is accused of having joined power. When he became an idol, when he arrived in a world so excluded from the power of the Brazilian elites — white, of course —, he did not deal with denouncing racism as expected of him, it was never enough.

For years Pelé has been required to confront the Brazilian racial structure almost as if he had betrayed his people. Unlike Diego, who was always criticized internationally for many of his mistakes, but passionately encouraged in his country, understood from a place of vulnerability and far from the demands that existed on the other side of the border towards Pelé.

Thus, the national issues of Brazil and Argentina reinforced the imagination of a rivalry that, in fact, does not make much sense. They never met in official matches; they were not in fact rivals. Some academic research in Brazil today, such as that of Ronaldo Helal, points to the media construction, especially from the 1990s, of an antagonism based on an impossible comparison that, in fact, represents soccer very well in its passion and irrationality.

More than opponents, Pelé and Maradona knew how to coexist in very different worlds that forced disputes. There were many public displays of affection between them, like Pelé’s words when Diego left us. In a certain way, they knew how to face violence imposed on them by the media, nationalist discourses and, let’s not forget, the question of race.

Que notícia triste. Eu perdi um grande amigo e o mundo perdeu uma lenda. Ainda há muito a ser dito, mas por agora, que Deus dê força para os familiares. Um dia, eu espero que possamos jogar bola juntos no céu. pic.twitter.com/6Li76HTikA

— Pelé (@Pele) November 25, 2020

Pelé leaves us just a few hours away from celebrating the end of a government that so much reinforced hatred, violence, authoritarianism and inequality. At the moment when we mourn the death of our King, it is moving to see that, in addition to what he gave us on the field, Pelé embodies in his own story a fundamental reflection on racism in our country.