As in the pages of an old script, the story of life legends appears: with cuts, repeated shots, and protagonists framed from different angles. Sometimes there are works that are not recorded on celluloid but are worthy of being a real film. The pages of this script begin with the following phrase from Cersei Lannister: “When you play the game of thrones, you live or you die. There are no intermediate points.”

Black screen and white letters: The story you will see below is based on real events. The events originated in Cuba and echoed in the most important places in the sports world.

A girl was running with her cousins and in every jump the prophecy was seen, superimposing that image on those of the jumps in those blocks or in the run of the century, which culminated with one of the most important finishes of all time in a volleyball clash. The sound of the clapboard marks scene 1 of Episode 8 with suspense music, which gives rise to a flash that zooms back from the stadium lights.

In the tunnel, a backlit image borders a tall, thin, dark-skinned woman. You can see the number 10 in white. Above the number, the letters form the word “Torres.” It is Saturday, September 30, 2000, in the Australian city of Sydney. A date to remember. Turning back, we travel to the past…

Episode 1. First sequences

Havana, 1985. A tense atmosphere took over the balance in the home of the 10-year-old girl Regla Torres Herrera. The separation of her parents was imminent and although this did not prevent her from having a happy childhood, it did end up marking the paths of her existence.

Years later, in front of the camera, in a medium shot, she is dressed in sportswear fitted to her 191-centimeter body, with the elegant figure that subtly sealed the actions in the games, like someone performing a ballet.

Her eyes are focused on the target with a sustained gaze and, in an out-of-focus background, Boyeros Avenue can be seen from the benches outside the Cuban Volleyball School. A quick transition takes her to her memories.

“My parents separated, but he continued to take good care of me and I went everywhere with my mother. Since she had no one to leave me with, she preferred to put me in a pre-EIDE, semi-boarding school, and that way she could be at ease. This is how my career began: because of a problem of necessity.”

Volleyball wasn’t even her choice. Her mother chose the discipline because she liked it, even though the tall little girl was interested in the high jump. She loved running at her grandmother’s house on the weekends, moments in which she felt free to do everything that eluded her from Monday to Friday. There she climbed trees and roofs, had friendly fights, and threw stones, sequences repeated on vacation when she went to Matanzas with her father’s family.

“I started with the teacher Bárbara Palmer, who had recruited me since preschool. I was always very tall for my age, with long limbs; however, I was very young and my mother didn’t let me, of course. Already when I was in 4th grade she gave her authorization for me to enter the pre-EIDE sports school. I didn’t know Palmer had convinced her. Not knowing anything about that, I I went with another teacher to do high jump tests and, when she arrived, the lady asked her:

“Are you the mother? Look, I did some tests and she was very good at high jump.”

“What, high jump?! I came here to enroll her in volleyball.”

“But she signed up.”

“The signature is worthless. She is a minor, so she is very young to be signing something. She’s going to volleyball, and that’s it.”

She spent two years there and in the 6th grade, she entered the Mártires de Barbados EIDE, until the 8th grade, when she did new tests and was taken to the national ESPA school for a few months.

There, already a teenager, Regla gave her trainers the first headaches. A shortcut she took to go from the house where she slept to the exercise areas, in what is today the Club Habana, almost ended up cutting off her progression; although in the end, it got her faster to the national team.

“I was not stupid in the classroom, on the contrary; but near the lodging house there was a carpentry shop and the carpenter was an older man. To get to school I took a shortcut along a trail that passed in front of his house and I saw him there, sawing, so old, and instead of going to the classroom I spent the whole afternoon helping him do his things. One day the coaches said that I had been discharged because I was missing classes and when they came to ask me…” she smiles out loud, “the problem was that I was also sawing, planning wood with him.

“That’s why I went to the Cerro Pelado school. Eugenio [George]’s wife, Chela [Graciela González], tried to make sure I didn’t miss the opportunity and transferred me. I was 14 years old. I played with the schoolgirls, went to competitions with the junior team and at that age, they promoted me to the national team. I didn’t have the level, but I had the conditions. Eugenio decided it so that I would grow and see how the international quality was. In 1989 I joined the group.”

Episode 2. The architect and the paradigms

Animated photographs of Eugenio George and the training sessions act as a curtain in the narrative thread. Due to the casualness with which Regla Torres had faced her short period in the national ESPA, it was difficult to believe that her maturity was going to arrive overnight. The new regimen seemed not to be compatible with her wishes, but her mother, for the umpteenth time, was betting more than her.

“Having arrived so quickly was a very abrupt change. The preparation was very hard. That caused me to reject him a little, because I was not used to such a big burden. That’s where my mother intervened, with such a strong of character; she was never one to spoil me when I was the only daughter. Almost like a military man. When I got home I told her: ‘I don’t want to continue. I can’t do those workouts.’ She forced me and said, ‘Yes. You have to be there. You can’t stay next to me. If the ball moves you hit it hard.’ We lived in a rather turbulent place, El Palenque, in La Lisa, and what she didn’t want was for me to have that kind of life.”

In this way, Regla lost her fear of training and the idea of leaving it did not appear again. She had a lot to take in and learn. Eugenio George made a great impression on her, she was overwhelmed every time the powerful gaze of that man fell on her because of her actions.

“He had a strong look. I saw him for the first time one day, at night. The junior teams in one field and the national team in another. And he told his brother, Eider George: ‘Send Regla over here.’ It was a sudden change too,” she laughs and the shot is of her joining her hands and moving her shoulders. “Just imagine, when I see those big women… I was almost this tall and weighed 65 kilos, and their thighs were full of muscles! I didn’t know what to do on the court, I put a lot of pressure on myself. Eugenio looked at me like that, like up and down and thinking: ‘And where did this come from?’

“He wasn’t one to talk much; he said many things just by looking at you. There I became one of volleyball’s most spoiled athletes, perhaps because I was the youngest. Both his wife and he spoiled me a little, but they taught me a lot. I always liked reading and he encouraged me, every time he saw me with a book he would come over to talk about it. He was a mason. A very cultured person.”

The spoiledness that Regla speaks of caused certain ups and downs at certain times; however, it did not prevent the mentor’s support both on and off the court.

“I owe him a lot. He was someone out of the ordinary. Sometimes he would call attention and you would start crying and saying things, getting mad because he scolded hard; however, you realized that he was right. It was a way of learning. When you had any problem, he would advise you, always for your own good.

“We weren’t very mature in terms of relationships, even though we thought we were, that we were the best, that we were lionesses… It wasn’t like that. He saw beyond everything because of experience, and culture. Maybe someone heard the collective scolding that he used to give and say: ‘Oh! He really talks a lot!’; but what for some people was cruel, not for us. We understood the language very well, which was direct. And as time passes we see all the teachings he gave us, preparing us for life. I don’t think any of us today is a person who has not achieved her goals. They are all successful.”

In those early days, the alias with which her teammates baptized her arose. Her physique and hairstyles were decisive: “They invented a nickname for me since I was so thin and tall and I hardly knew how to comb my hair, because I had a lot of hair, they called me ‘El gajo’ (A tree limb). Tania Ortiz, Mireya Luis, Regla Bell, Magaly Carvajal, Lily Izquierdo, who was the one who combed my hair, all took part in my education.

“They taught me how to behave. One arrives with certain habits and when you are in another scenario, among habits that they knew, they advised you what to do. Now, as adults, that respect still exists with these older athletes, they really were our mothers.”

Seeing the actions of Lázara González always generated in her the wish to be like that volleyball player. She conceived herself in that pattern at all times and to this, she would add the example and the drive of whoever was her teammate in the center of the field: Cuba’s number 15, Magaly Carvajal. Archive images of her teammates alternate on the mind’s projector.

“Lázara wore the number I liked: 10. I wore it from the EIDE until the end of my career. I was a center-back like her. When I got to the team she was retiring and I started to notice Magaly Carvajal. An excellent player, one of the best center-backs in the world. Having her close and getting to play with her was a privilege. She had a fighting spirit,” she expresses passionately, “the way she performed, she was very aggressive and trustworthy.

“Mireya and Magaly were impressive; Regla Bell too. It was a privilege to join that group, they were all great. Watching Magaly block was a spectacle, watching her attack a ‘tiny’ move… Little tribute is paid to Magaly here, the same happens with Regla Bell, and they were phenomenal athletes, just as much as Mireya Luis, although I speak in the sense of how Mireya and Yumilka Ruiz and I too are mentioned; but justice is not done to these two. Regla Bell never left the field in her extensive sports career as well as Magaly Carvajal’s career, what happened is that she retired much earlier.”

Episode 3. Face-to-face: a brief exchange

She continues on the bench and now the shot closes in a bit. In the lower-left corner of the screen, the questions appear, one after the other, and Regla answers them as when she blocked the rival attacks.

“Where does the strong character that everyone says you have come from?”

“My parents are strong-willed. Although I’m not like that all the time. I don’t like impositions. You get what you want from me with good manners. I dislike lies. It’s like they put a black veil on me and all reason disappears. I become blind if a person I trust deceives me. I prefer to have few friends and have them be true. I also can’t stand hypocrisy, when something is wrong I have to tell whoever it is. That has caused me a lot of problems inside and outside the team. I’m not interested, I have to say what I feel; if not, I feel bad and until I get it out of my system nothing is good. I have made mistakes because of this. With age, I have learned to express what I think in other ways. I really like parties. I enjoy humor with the people I know, talking nonsense, making jokes… all that. I’m not one to make friends with just anyone, you need to earn my trust and few people have achieved that. I get along with a lot of people, but not all of them have my trust. When someone passes the barrier of not judging me, they already have at least my affection, meanwhile, I’m not interested, because you are a superficial person who gets carried away by what people say without knowing me. That’s why it might be a little difficult.”

“Why is it said that you and Marleny Costa were the most undisciplined?”

“Because we were continually inventing things. Mireya would sometimes say: ‘Tomorrow blue blouse with red shorts,’ and we would show up in other colors. Furthermore, we were very argumentative and they punished us a lot for that.”

“How were you punished?”

“For example, waking people up in the morning for two weeks or a month, carrying the balls, schedules… Taking charge of everything for that time. It was hard and Marleny and I were always irresponsible. That was why she used to get into fights with Eugenio. Chela wasn’t as strict and controlled the situation between us.”

“Eugenio mentioned on one occasion that he had to get tough because it was not easy to lead a squad of women. What made them difficult to lead?”

“Everyone has their own way. That was crazy. He sometimes said that we were a team of sick women,” she recalls, laughing. “We did a lot of bad things and played hooky because there was so much stress from training and playing that we didn’t have time to go out dancing and when we were out there sometimes we would all agree and run away to a disco. They thought we were sleeping. The next day, people stayed up late drinking and we said: ‘Come on, don’t let them notice that we went out dancing!’ Things done by young people, difficult, strong women, with different personalities. Leading a group like that was not easy. Sometimes he would scold and we would sit still and then laugh. He noticed it; but he didn’t do anything, otherwise he would go crazy. We had a complicated character and we did things that no one would think of.”

Episode 4. From Havana 1991 to Barcelona 1992

A panoramic view captured from the ground along the road proposes the image of the Cojímar Olympic stadium, which contrasts with the stills of the beginning of one of the worst economic crises experienced by Cuba. At the beginning of the Special Period, the island hosted the eleventh edition of the Pan American Games, marking the second time in history that a delegation anchored above the United States at the top of the table of medals. Before, only Argentina had achieved it, in 1951. The Cuban representation ranked in first place in the table of medals with 140 gold metals and volleyball’s medal was there, a title that also went to the personal record of a young Regla Torres.

“I hardly played. They only put me in one match, but I really liked having participated in those Pan American Games. They were incredible in all aspects: the organization, what was felt in Havana, and being in front of our audience, which was always elusive since we were not lucky enough to perform so much here in Cuba. The few times it happened was a privilege, because the family, the friends, the people who have always followed us a lot and still do today were there.”

“Did you feel unhappy while you were not on the court?”

“I would have liked to participate more, but I was not yet fully prepared to enter. I was missing quite a bit.”

However, the Barcelona 1992 Olympic Games would be a big surprise for her. If in 1991 she thought being a titleholder would still take a while to achieve, Eugenio had other plans. In the telereceiver, aerial drone shots move over Barcelona’s Las Ramblas and the movement of the simulated waves on the floor of the city promenade takes the Cuban crew to the Poblenou Olympic Villa, in the Sant Martí district; although Regla does not have many memories of the event.

“Almost none. You’re going to think I’m a disaster,” she laughs again. “Until then I was among the substitutes and I started as a regular in an Olympics. Imagine, that’s something you don’t expect. I began to interact with Mercedes Calderón. When he called me: ‘Come on, you’re going in,’ I got a shock…and Norka Latamblet said: ‘Come on, calm down, do what you know how to do in training.’

“The luck was that since the others had so much experience, they provided a little support and my rookieness was not evident. I was more focused on things not going wrong or doing my best that I don’t even remember who I played with or what I did. I only thought about not being out of place to keep me on the court. I know they gave me the medal. That’s it.”

With the final point achieved against the Unified Team after an ace by Magaly Carvajal, Regla Torres became the youngest gold medalist in the history of Olympic volleyball.

“Later over time, you come to value it. At that moment for me, it was winning one more competition. I didn’t have the ability to say: ‘This is an Olympics, I’m in the Olympic Games.’ Later you see the importance with which other people talk about the event and you say: ‘Hey! I am an Olympic champion. But at that moment you don’t make a lot out of it, at that age you are not mentally prepared to realize the magnitude it represents.”

Episode 5. Sao Paulo 1994

The set design that showed the Ibirapuera athenaeum was capable of making any visitor doubt. The Brazilians had dyed the facility yellow and the noise and hubbub were abysmal.

The fans of the South American giant were betting on their team’s victory in the World Championship, but the Cubans reached the finals undefeated, without having lost a set to any rival. Regla and some of her teammates had been crowned junior world champions in that country a year earlier and that nation’s media coverage added fuel to the feat.

“We always thought about winning. Getting there and shredding everyone. Winning 3-0 was something out of the ordinary. What is it that incites us? In this tournament, the Brazilians, whom we already had a quarrel with them, changed coaches and Bernardinho, a super coach, always put a lot of things into their heads and they began to truly believe it and talk more in the interviews. For them there was no other team than Cuba, they did not take into account Russia, the United States, China or anyone else. Their thing was Cuba, they were going to defeat us, because they did it in the Grand Prix.

“They thought the same thing would happen again: ‘We beat them once and they’re not going to beat us again,’ that’s what they said. Seeing that, we thought: ‘Look at these crazy women.’ They never understood that provoking us was worse, because that’s when we played the hardest, maybe in the Grand Prix they beat us because we relaxed a little. However, when they started flirting in the game, things got complicated. Mireya would get really upset, and Regla [Bell] too. Everyone got upset and that was when they couldn’t.

“They talked too much and it cost them dearly. Look how we entered, that the first set was 15-2 in a room where it was impossible to do what we’re doing now: not even you could hear me, nor I you because of the noise. They threw peanuts and Coca-Cola cans on the court when they called for time. We didn’t care about any of that. We played using signs so as not to tire ourselves out shouting. The first points were blocks from Magaly; psychologically it ended them. In the second they gained a little more confidence and reached 10 and in the third, it was 15-5. That was terrible for them in a place where they were supposed to be favorites because they were the local team.”

A zoom-in goes through the headlines of the newspapers in which the Cuban team is reviewed as the most valuable and the best blocker and, curiously, when Regla talks about it she makes it seem somewhat irrelevant: “You get used to it. It is not the important thing: the most important thing was winning.”

Episode 6. Atlanta 1996: second gold and take 2 against Brazilians

In crescendo in brilliance, like Cuba’s participation in the Atlanta Olympic Games, are the videos that precede its performances. When trying to ask about the uncertain beginning of the Morenas’ path in that event, Regla Torres barely lets me finish the question and starts with stories of beauty salons, fights and, also, triumphs.

“The Cubans? Disconcerted, at the hairdresser. It’s just that we were used to a unique style. Eugenio was very rigorous regarding discipline. All the other teams were in the normal villa, walking around. We weren’t allowed to do those things. He knew we would be disoriented quickly. People were going to dance, they had recreation and we wanted to feel a little bit of that. But every time we went off course, we lost.

“Inside the villa, they opened a salon. The hair straitening cost 5 pesos and washing your hair and setting your hair was free. Just imagine!” she smiles. “Everyone at the hairdresser and ‘what if they cut my hair and did that hairstyle’ and we were not ready for the competition and Eugenio making a fuss. Until we realized: we lost to Brazil and Russia, and the tour was going to finish because we already had to eliminate Brazil, which was a tough rival.”

The way in which the group got out of the bumps could be described as unorthodox, although effective, in a squad of women with a strongly marked character.

“That’s when we started fighting. We did it a lot, we had that good thing. When one saw that one of them was getting carried away, discussions began. Hard. We are even talking about blows sometimes. That’s how we solved the problem and sometimes people would say, ‘They’re animals.’ No. It was externalizing everything if there was a problem between us. That happens in a team and more so with women, there comes a time when you are not liked because of a certain situation or something happened between you and me, and that’s it.

“That couldn’t be taken to the court. If you didn’t talk to someone because of any difficulty… She was your teammate, you needed to resolve it before entering. Eugenio did not intervene in the discussions. In the dressing rooms we said horrors to each other, we expressed everything. We were all terrible, don’t let anyone tell you anything else. If it worked for us to remove everything that could cause discomfort so as not to bring it to the court, welcome: ‘Hey, we’re eating shit, get on with this…’

“And that’s it. Just out of respect, you had to do well, because you trained very hard to get to a place and not want to win the competition. Besides, you couldn’t afford to fail much; everyone had a level there, those of us who were playing and those on the bench, who often didn’t come out because we didn’t give them a chance. We knew that if we gave them a chance once, we wouldn’t go in again.”

The semi-final match against Brazil is one of the most remembered and not only because of the game played on the taraflex. For the umpteenth time, the Brazilians had the hope of defeating the Cubans in an important clash, with the taste of victory still in their mouths, after a 3-0 defeat against the Cubans just ten days before.

The images of the confrontation for the ticket to the finals appear in a transition. August 1, 1996. In the fight, a partial is distributed for each team and they reach the tiebreak. A shot by Mireya finally seals the Cuban victory and once again the Brazilians look impotent. The players from both teams group in a tumult with the net in the middle. They start pushing each other. Márcia Fu crosses to the Morenas’ side of the court. Magaly Carvajal grabs her by the neck and returns her to her side. At that point, the only thing that had finished was the volleyball challenge.

“It was a very hot game, too much. They said things to us and we to them. Put yourself in their place. I understand them, it was frustrating. They kept that inside, they had beaten us in the preliminary. We screamed and it continued later in the dressing room, with fistfights. There was an incident between Ana Paula and Raiza O’Farrill and afterward, there was a noise in the locker room, which was nearby, and that was a mistake. We exaggerated with the fighting and there was a police officer standing at the door of Brazil’s dressing room so that we wouldn’t pass and they wouldn’t come out.

“[Idalmis] Gato got in under the guard’s feet and began to deliver blows. Since I couldn’t get in, I grabbed some Coca-Cola cans and threw them inside. That was terrible. So much so that Eugenio told us before the finals not to walk around the town alone, because, since it was so horrible, they were capable of doing something to us so that we couldn’t play and lose in the finals. We were all together until the Olympics were over.”

The situation in Cuba was becoming similar to that of 1991 and the reproductions of the shortages of the Special Period, accompanied by a gloomy instrumental, precede the question.

“Those were difficult years for Cuba. What did it mean to know that this title was a kind of incentive for a country that was having a hard time?”

“Eugenio always talked about it a lot. We had to respect the people. We were going through a very bad streak, Special Period, but when we got here we saw that people didn’t miss a game and you realized that, even if it was on the radio, everyone was eager to know what the volleyball team did. That deserved respect on our part and to always do our best to not disappoint the Cubans, the family.”

Episode 7. The Sydney preamble

In 1998, Japan hosted the World Championships. Cuba retained the title and, like four years before, Regla turned out to be the best player and the most effective blocker in the competition. That lethality on the net, a nightmare for all rivals, is attributed to her will and her aggressiveness on the court. There are those who separate the game from their lives, in her case, it was not like that, even in moments where her body took her to the limit.

“It was something personal, that’s why I was so aggressive. I disliked being yelled at when they blocked me, it was something that said: ‘Look at this crazy girl… Hey you, repeat the pass over here.’ And what I had in mind was breaking her finger, going over the blocking, or hitting someone on the head on the other side. There are athletes who did laugh, a little more relaxed. I didn’t like to laugh a lot. Willpower is also important, necessary to wake up every day with ovary pains, pelvic inflammation, fever, cold, and train like that, because Eugenio said that this could happen in a competition.

“I had knee problems for more than half of my career, I was operated on three times, twice on the right and once on the left,” she says, while the lens captures the palms of her hands above the joints, “and there was practically no time for rehabilitation, many events came in a row and the pain is always yours. You had to put up with those discomforts that were terrible and sometimes made you want to hit your head against the wall; it was too much. Pérez Vento had a saying: ‘Never say that pain kills you.’ That motto was true, you couldn’t allow it, there was always someone willing. I remember that I infiltrated my knees a total of 14 times, they gave me two shots at a time: you rested today, a little ice, and the next day you continue.

“It was one of the things why I retired: I didn’t want to feel more pain, go back to rehabilitation, have surgery. It was like starting in fourth gear, you weren’t totally ready, but you needed to do it. And I didn’t want to start in fourth gear again.”

In the 1998-1999 season, she was in the Perugia Club, in the Italian league, but an untimely injury to her knee made her miss the 1999 Pan American Games in Winnipeg. Her mother supported her a lot to get ahead. Upon return, changes were being made to the volleyball regulations, the scoring system was not the same and that had an impact on the game.

“Cuba was always a physical team, at the time of the ball change when the opponents got tired we were just getting started. That doesn’t mean we didn’t also master tactics and techniques. We never leave aside our essence. We played a different game than everyone else, the 6-2 score characterized us and gave us an advantage over the other countries. We did not see the difference with the implementation of the rally point, you had to play more technically and tactically concentrated to fail less, and our years of preparation served as a basis.”

Months before the 2000 multinational competition under the five rings in the city of Sydney, the Morenas del Caribe won their second title in Grand Prix tournaments, a title that had eluded them since 1993. The monetary stimuli distributed in this type of event have always been the cause of comments and speculation on the streets. The close-up of her face captures her seriousness.

“These awards arrived late to Cuba. Sometimes they took a year and we got paid 50 Cuban pesos at that time and the exchange was 100 pesos for one dollar. Just imagine, Special Period. Then we became desperate. There were those who had children and large families and we were the backbone of our homes. At that time, getting soap was difficult and we provided the family with what was necessary. We had to pay for gasoline, electricity, medicine and 50 pesos was not enough. We depended on these prizes and sometimes there were disagreements and when a year passed and we had not received payment they told us that the money had not arrived.

“It was difficult, but it did not prevent us from fulfilling our role. It became unthinkable. Sometimes we would tie a competition with the other and we would still arrive here with financial problems. We played for ourselves, for Cuba. We needed money, like everyone else. This shows that, despite these shortages, we never jeopardized a result due to a payment problem, although we did have a hard time.”

Episode 8. Sydney, September 30, 2000

You can see the number 10 in white. Above the number, the letters form the word “Torres.” It is Saturday, September 30, 2000, in the Australian city of Sydney. A date to remember.

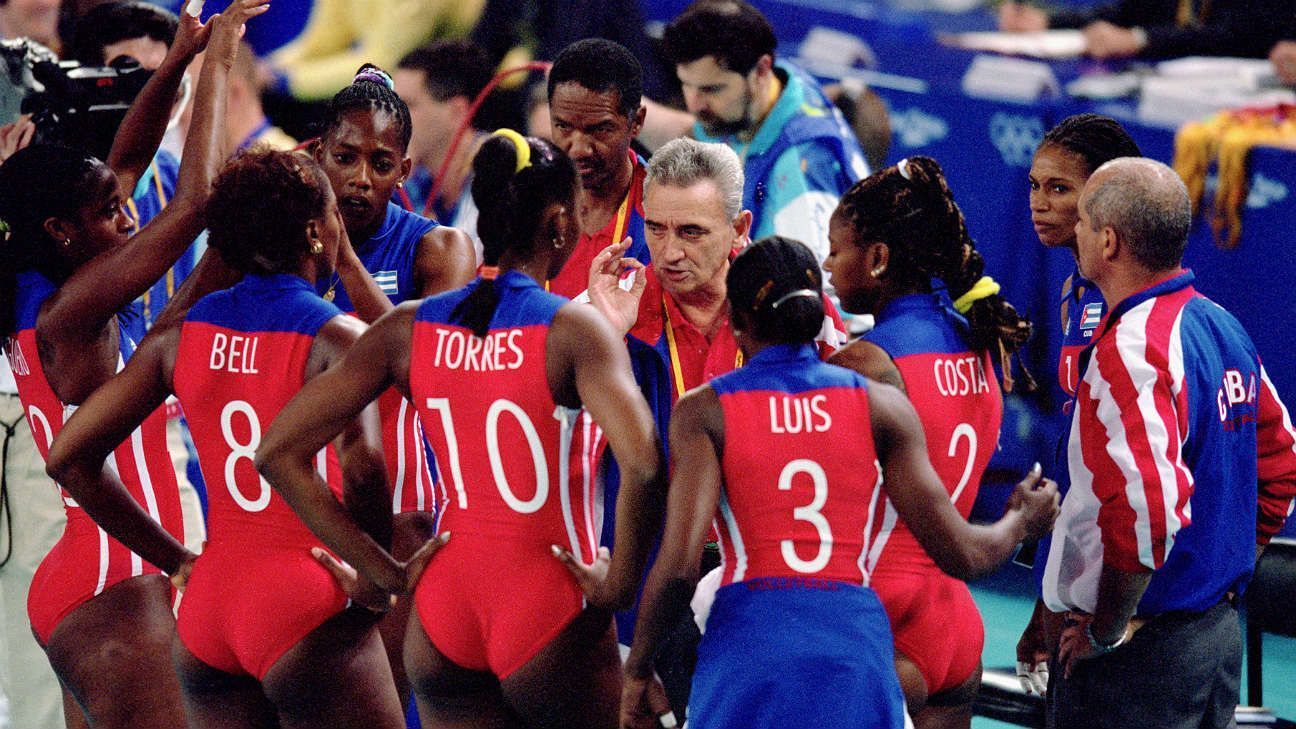

Tense soundtrack accompanies her as she walks through the tunnel. The backlight becomes weak and the image begins to appear in color. The 10 leaves the taraflex of the Sydney Entertainment Center. It is the finals of the women’s volleyball tournament of the Olympic Games. Regla Torres stands as Cuba’s main figure on the court. Ahead are the Russians, led by Liubov Chachkova and Evguenia Artamonova, who had defeated them in the preliminary phase three sets to two, just 12 days ago.

The Cubans play well, although they seem somewhat unfocused. There are things that just don’t work out. Number 10 has a straight face, she talks a lot and when she gets a point she can’t relax her expression.

The match is close. She gestures to her teammates to continue calmly. The score became 24-21 after Regla caught a tame ball over the net and nailed it into the opponent’s court. Only then does she smile, but anxiety takes over. They seemed to celebrate the goals before they were scored and the Russians tied at 24. Finally, the girls led by Luis Felipe Calderón ended up losing the first set 25-27.

The lens does not leave the Morenas’ half of the court. In the second set, the wear is even greater. Chachkova is a whip and continues to drill the wound. Regla continues to ask for calm. She almost collided with Agüero trying to lift a ball. The cameras look for her in every action, positive or negative. Together with Yumilka and Regla Bell, she pushes and the Cubans are up 22-21.

Once again the possibility of winning escapes in several key actions that do not materialize. 25 points are not enough. The fans of the Eurasian nation do not stop singing and waving their tricolor flags in the boxes.

Regla misses a shot that goes long. Slow motion captures her with her hands on her head. A gesture of patience. It is necessary to continue up to 30. It is also not enough. The battle between both opponents does not end until the Russians score 34-32 in their favor. The sequence freezes on the scoreboard and comes to invade the mind, with that effect of blurred edges and a black and white screen, the fears, the sacrifices, the commitment, and the taste of success. The latter inherent to that group known as the Morenas del Caribe.

“In 1999 I had my second operation and I didn’t feel good afterward, because I was still in pain and I couldn’t train hard, so much so that my knee was infiltrated in the Olympics so I could play without discomfort. At that time I couldn’t run the track well or do deep squats. I was a little out of balance physically and had to make a double effort to catch up with my teammates and face a team like Russia. That final match took the life out of me, in the last points I couldn’t feel my knee. I said: ‘My God!’ It was a dull pain, after that came the ice packs. It was difficult.

“We had already been defeated by them. We met again in the finals, there was a lot of anxiety and at times confidence was lost in what the partner was going to do, so that, for example, one would want to get involved in a receipt that was not hers, because she thought that the other wouldn’t do it well. It was the third Olympics, it meant a three-time consecutive championship and we all thought the same thing. That made us disconnect for the moment. So, after the second set ended, there was a confrontation. We said a few things to each other and we came out calmer.”

Behind the scenes, an inquisitive voice sneaks into the recording and makes it remove the complex moments of the Olympic finals. The letters in yellow, as a subtitle, say:

“How did you experience those moments of adversity in the finals?”

“There was a moment when I thought: ‘It can’t be possible. How is it possible that after swimming so much we are going to die on the shore?’ You lose concentration because you start paying attention to the others’ game. I was very restless with it and talked a lot, so I disconnected from what I had to do. In the third set, I said to myself: ‘Regla, shut your mouth a little! Be quiet! Leave people alone, everyone knows what they should do.’ What I wanted was to convey a little calm and patience.”

The image on the screen slowly dissolves to black and a sentence in white letters marks the challenge’s fate: ‘The difference between winning and losing is often not giving up.’ Walt Disney.

In a succession of quick cuts, you can look at one point after another of the Cubans. Something changed. Like when the protagonist gets up after being almost completely destroyed. In the third and fourth sets, the Europeans did not exceed 20 points, falling 25-19 and 25-18. The sound intensifies and the voices of the speakers in various languages are heard over and over again: Regla Torres with the spike! Torre blocks! Ruiz! Double-blocking by Cuba! The pass for Regla Bell…. Point for Cuba! And the images filmed one after another. Flashes of brown skin and red hitting the opponent’s optimism like a hammer.

In the stands, the public applauds and shouts: Cuubaaa…Cuuubaaa! The scene is set for the tiebreak and the Russians’ morale is plummeting. Their dull faces, with the expression of the most infinite concern and a hint of fear, complete the picture of the sentence.

The last set was confirmation that the third consecutive gold was more possible than ever. And Regla gave a recital. After a run after an excellent service from Taismary Agüero, the point brought the Cubans together in the center of the court. Her face seemed to have finally relaxed. A conviction could be read on his lips: ‘Let’s go!’ The clash advances and the Russians simply cannot. With the score at 10-7 on the European bench you can already see desolate faces. Defeated. Not even the temperamental Karpol shouts and his pupils do not exceed seven. With point 14 for the Cubans, the feat was evident.

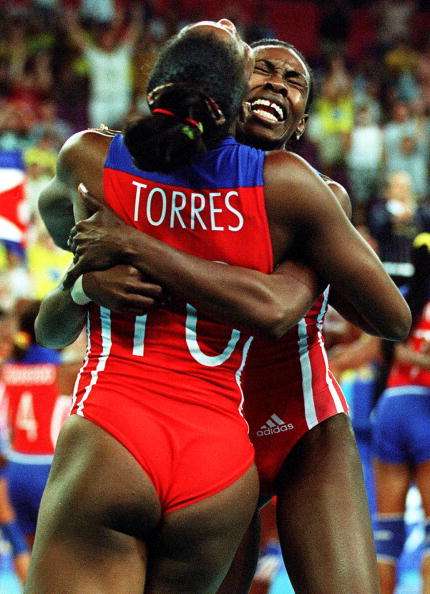

The ball enters Cuban territory in slow motion. Marleny Costa sends it to Agüero and she makes an electric pass behind her, to the right end of the court, where the player of the match, the most valuable of that Olympic tournament, runs. She hops on one foot and gets her arm ready. Everything freezes there with the sound of a photograph being shot, to, with special effects, appreciate the beauty of the action in all its angles.

“That’s phenomenal, because every time they show that spot, I see myself 30 kilos lighter,” she jokes, “and that action, which is very beautiful, I feel proud. I say: ‘Oh look how skinny, how pretty!’ Proud that that point has meant the end of such a difficult challenge, of an era as fruitful as ours.”

The time between takeoff and the spike lasted like a flash of lightning. The ball hit and she raised her head to the sky, with her eyes closed, as she began to jump until they hugged her. They all jumped. Millions of Cubans did it too.

Episode 9. The bittersweet taste of a prize

“The queen of elegance. She could have been just as successful as a model, dancer, or athlete in any other sport. With her body, her bearing, and her class, Regla Torres Herrera would have been the ‘number one’ anyway…. Her wall is practically insurmountable, in attack almost no one reaches the ball like her. She is beautiful, skillful, energetic. The best player in the world does not lack character.”

Volley World Magazine, published by the FIVB.

Moving images run through the pages of the magazine containing these words, which were accompanied by the award for the best volleyball player of the 20th century, given to her on September 21, 2001 in Berlin. There Eugenio George was also awarded in the coaches section and the Japanese women’s team was incredibly chosen over the Morenas del Caribe.

The award was a source of controversy and led to mixed feelings that ended up damaging her environment and her confidence.

“There have been so many great ones. Just in Cuba there are Mamita Pérez, Mercedes Pomares, Lucila Urgellés, Magaly Carvajal, Mireya Luis, Regla Bell…. That’s only here, imagine if I start mentioning outsiders: Lang Ping, Caren Kemner, Márcia Fu. There are many that could have been the best of the century. For me, it is an honor to have been named. It brought me problems and a lot of disappointment. There was a moment when they made me feel bad: ‘No, but not Regla, because this, that.’

“Several people said yes, some said no. Others said either of the two, referring to Mireya. It brought about a lot of counterpoint and it made me very sad. The day it was mentioned, journalists questioned it. Anyway, it was a Cuban. What was the problem? So, that was another of the reasons that caused my retirement. Determinant, apart from the physical pain.

“They never dedicated themselves to investigating how this selection was done and why they did it. At no time did they communicate that the second on the list was Lang Ping and that Mamita Pérez was among the 15. It was never said here. I don’t know if it was because it was not convenient or because it was more advantageous for that controversy to continue. I never said anything either. For me, the important thing was to have been part of a team that won three Olympics, and if I was not the best player of the century for many people, at least I was among the best. And that alone is super important. That’s how I thought at first. I completely rejected everything related to volleyball.

“What they did was criticize. It was ugly. So unpleasant that they even went so far as to say that the president of the International Federation was in love with me and that’s why they gave me the award. And that’s enough, I said: ‘Regla, you are shit. I am done.’ It marked me a great deal.”

“Did it bring differences with Mireya?”

“There was a moment that yes. Afterward, she began to let it slide. Why, what happened? This is the most important thing: there are people who take advantage of situations and some may tell others what they want to hear and many people took advantage to issue criteria and create hostile environments. It was quite unpleasant,” she emphasizes. “And since I cannot be hypocritical, I felt resentful in those moments and I withdrew, isolating myself from everything and everyone, because I felt very bad.”

“You didn’t look for the prize. However, did you have the merits to deserve it?”

“Then I dedicated myself to watching the games, to being critical of myself: ‘Did you earn it or not?’ And I say: ‘Yes, Regla, yes. Why not? Why do you feel bad?’ If I hadn’t deserved it, anyone who knows me knows I’m like that, I would have said: ‘No, this has nothing to do with me.’ No problem. Then I said, ‘Rule, why did you let people make you doubt your ability?’

“It is true that there are athletes who spent much longer on the national team, but within this number of victories that we had, the only ones in which I was not there were in 1989 and 1999. In all the others yes, and winning awards, it wasn’t that I passed by there. I was the best player in the two World Cups, the best blocker, the best receiver, the best defense. That tells you a lot, because it wasn’t a competition. The people who determined this are not far from the truth. I had to give myself psychotherapy to be able to accept and see those things over the years.”

Months later, Regla Torres joined the national team for the World Cup in Germany in 2002. The lens follows her through the empty stands at the beginning of a curtain and a close-up of her face in profile shows her feeling of extreme pain. She had lost an advanced pregnancy and the sport was a help to get out of the rut, although the whole situation explained above did not leave her feeling well either. Impotence was the word of those moments.

“I could have said all these things at that time, however, I didn’t want to give so many explanations either. I felt helpless, but at the same time, I didn’t want to talk. I didn’t even want journalists to come near me, so I reluctantly gave interviews, because I don’t like them very much and I did it when there was no other option to avoid giving a bad vibe. I was very reluctant to do anything related to the sport.”

In Europe, she was not in shape to be a regular player and that was her last appearance wearing the national team jersey. At that time, she decided to stop, despite being only 27 years old. After marking crosses on her calendar for a long time, in 2005, a whimsical desire took her to the courts again.

“I got a little ticklish and said: ‘You can play.’ And to prove it to myself I went to Italy, to the Padua club. I was there for a few months and I confirmed that I could. Then I realized I didn’t want to do it, so much so that I didn’t finish. That was the final point. My age was OK, I could have participated in five Olympics, however, I didn’t want to know anything more about that.”

Episode 10. From the prism of the Cuban school

A cut gives way to the new sequence in a pan through the corridors of Boyeros’ striking installation. She has been there since 2008, when, after a call from Raúl Diago, she began working as a coach at the volleyball school.

For several years she was a member of the technical team of the national team, which represented a responsibility and, in her words, causes mixed feelings due to the decline in results experienced by the discipline. The recording time numbers do not stop and the red “REC” button flashes, in the same medium shot at the beginning of this story.

“Volleyball is going through its worst moments. There are many girls who could achieve what they set out to do, others who have already passed could have done it too. The problem is in the will and desires. It’s not bad to be ambitious if you want to be a great player. I always give an example of an athlete, who I saw as a child holding hands with his mother: he is Robertlandy Simón. He came to school at zero with a strong conviction of being a volleyball player. So much so that he would arrive before training and start doing extra work, they would finish and he would stay. In less than two years he became an excellent center back, one of the best in the world.

“When you want to achieve something, you do it. I am an enemy of conformism and mediocrity. I can’t be in a place to be one more. If I’m going to be there, it’s to do the best I can, if not, I’m not here. I’m looking for something that fulfills me, not what dad wants or what is going to solve the family’s problems. It is not like that, because you neither solve nor become anyone. You pass by a place for nothing.”

17 de Mayo 2022.

Foto José Raúl Rodríguez Robleda

What has been missing and brought the discipline to the places where it is now is a mix of factors. Times have changed, concepts and people have changed. She has a pretty complete view of the whole situation.

“There are those who have desires, but that is not enough. They must know that everything in life is sacrifice and nothing is easy and to become a world-class player you have to give absolutely everything. You can’t reserve anything, you have to give everything every day, not just when you feel like it.”

She uses the United States Dream team in basketball as an example to make the comparison and her face shows traces of unanswered questions. If well-known figures, NBA stars, went to Barcelona 1992 and gave everything for their country, with a sense of shame, how is it possible that that cannot be achieved in Cuba?

“It got lost. The players are my size at 16, so there are mixed feelings. I see that they have the potential, what is missing? Believing it. And coming out on all fours after practice, without being able to walk because you gave everything. That’s the only way things are achieved. Sometimes I want to fly off the court. I can’t understand that the coach has to pester the athletes so that they give the maximum effort. I don’t get it.

“We come from a time when we won to place the name of the nation, the team and the family high. We played because we liked it, to be the champions. A team from an underdeveloped country, we didn’t have a cent and, nevertheless, we had that pride, that way of saying: ‘I am the best.’ That is missing and not only in volleyball. I don’t know what’s happening and it’s very sad to see this.”

She appears dismayed in the foreground as if searching for answers or arguments that reinforce the causes of the downturn. Forgetting or putting aside successful methodologies, as well as the loss of the ESPA and the academic demands on athletes, are factors added to the list of conditions that have caused the debacle.

“Before we trained a lot and Eugenio was criticized a lot for his methods and, mainly, because he is not present to defend himself. The results say it all. I think the training philosophy of the women’s team has been lost a bit. Women had a fairly high burden, completely different from men, and there was a time when they wanted to erase Eugenio’s school, his way of working. For a long time, it was obviated and practice was like the men’s team. One thing has nothing to do with the other and that’s where the difficulties began.

“The 6-2 has been rescued. It is complicated, but pertinent because it seems to me that there is no other way to demonstrate that Cuba triumphed by always doing it differently from everyone else. We are lucky to produce explosive, bouncy volleyball players who can afford a different style of play. We have wanted to do it the same as the other teams from 2004 until now and it has not been achieved.”

She also emphasizes the need to point out that we are talking about a sports school. “It’s not that you stop studying. After sports, you have to have a life. Today the study schedule of teenagers here is the same as that of people on the street. It’s not possible. You are one thing or another. They go to school every day, they received a significant physical load in the morning, and in the classroom, they fall asleep. That body is battered from training three or four hours at full speed.

“Not everyone is born to be a graduate, that is a lie. Before there were other options like senior high and you studied whatever you could. They finish school at five and it’s run, because at that time we are waiting for the second training session. It happens day after day and in the end, they do not develop in one thing or another. It’s something that doesn’t let us pick up.

“Besides, in the provinces, there are many difficulties for children to practice, balls are needed and sometimes there are special areas that have only one ball and a child needs many repetitions to improve. Here they come, sometimes, not knowing how to run, very bad technically and physically. So, we must train them with very little time. This has caused volleyball to go backward, and will continue this way until these issues are resolved.”

Post-credit scenes: other facets

As the closing titles slide by, she recognizes that the most pleasant moments of her career are winning a World Cup without losing a set (1994) and the three-time Olympic championship achieved in Sydney.

“What does it take to be your friend?”

“Being sincere. It’s very difficult to find someone who tells me I’m wrong and I can’t stand people who agree with me just to be nice to me. If I’ve been wrong, I need to hear it. Only those who appreciate you can do that and for me, it is very important. I hate lies. Sometimes I can be a little resentful, because I give everything in a friendship, but don’t fail me, I’m not able to forgive easily.”

“Who is the best player you have seen?”

“The Cubans, because they’ve been spectacular. Mireya was a leader, a captain, she knew how to control us. Impressive to see her take off next to you at that height from the ground, the power of the attack, that does not exist and will not exist for a long time. Magaly Carvajal was super aggressive, she blocked like men and she was beautiful, with a lot of drive and push. Regla Bell was more even-tempered and very constant.”

The last shots are more personal. Maybe in her car with sunglasses and going for a drive along the Malecón while she listens to hip-hop, rap, or Yoruba Andabo, to relax after something stressful. Or, perhaps, a homelier Regla, reading a good book accompanied by sweets, chocolates, and “everything that makes you gain weight.”

Being happy is the goal, sharing among friends, without paying much attention to drinking, with her husband and her pets: a pit bull, a dachshund and a Swiss shepherd. Something is missing to complete the frame and that is having a child. “This doesn’t mean that in the future I won’t be trying to be a mother, not only those who bring a child into the world are mothers. I don’t want to miss that opportunity.”

“The Morenas.”

“The best thing that happened to me in my life, I am an only child and I spent a lot of time sharing with colleagues who become your sisters, whether you like it or not because they are with you all the time. We are different, we have different ideas, and you must accept it because they have spent with you the good and the bad. If I am born again with knowledge, I would like to be part of this team because of the results and what we represent for society.”

She admires the tranquility and its space. She also thinks that people label her as a slightly strange person. But she already mentioned it: it is not good to judge without knowing. The credits are ending. The last shot shows her back, out of focus, watching her favorite series on TV: “Game of Thrones.” Everything dissolves to black in a fade out, but not before reading the sentence of one of the main characters of the plot:

“Never forget what you are, the rest of the world won’t. Wear it like armor and they will never use it to hurt you.” Tyrion Lannister

*This interview is part of the book “Tie Break con las Morenas del Caribe,” published by UnosOtrosEdiciones.