Universities in the United States have become a nest of student protests. Basically, their participants demand an end to the Israeli military offensive in Gaza, an end to the genocide of the Palestinians and that the United States government cease its political and material support for the State of Israel. They usually carry signs such as “Free Palestine” or “Stop the genocide” and ask their educational centers to cut all ties with Zionism and its institutions.

In this panorama, Columbia University occupies a prominent place for having established camps to protest and demand this change. They lit, in fact, the spark that spread over the country’s universities, from east to west, thereby increasing tensions in the midst of a divided and polarized culture.

From those in power, the central issue is how to end these protests and camps. Authorities have used force and issued ultimatums that have led to clashes. About 2,000 people have already been arrested in Texas, Utah and Virginia and California…. The New York police have stormed the Columbia campus making dozens of arrests after students barricaded themselves in Hamilton Hall, historically a building that symbolizes resistance.

These protests, however, are not a new phenomenon. And, above all, they refer to the strategies used in the 1960s and 1970s by the civil rights movement and against the Vietnam War, both in universities and outside them. The protesters are riding, as one of the protagonists of those days said, “on the shoulders of their grandparents.”

1

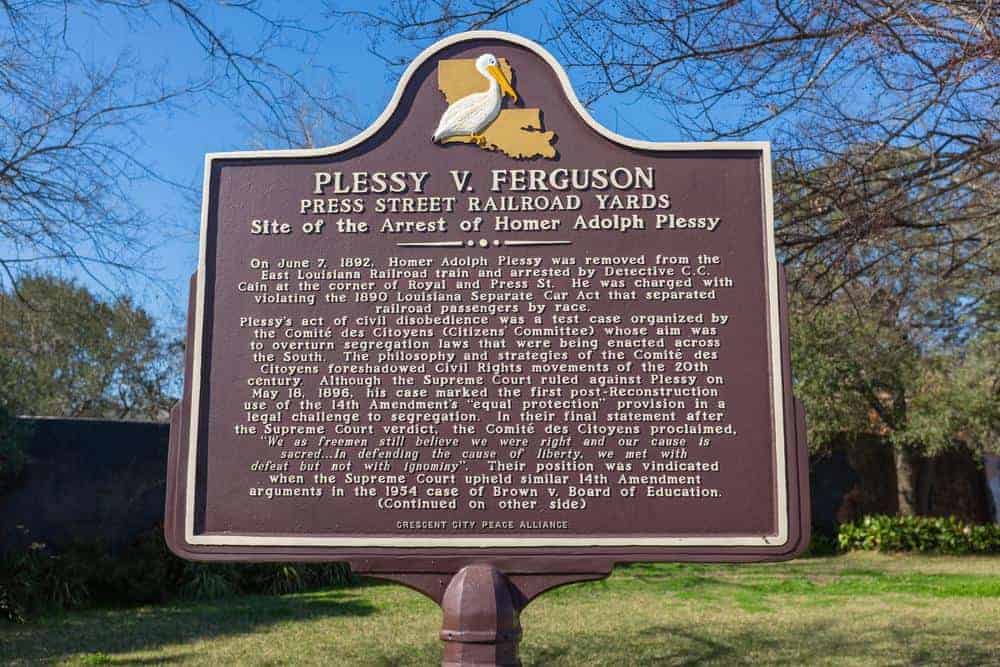

In 1890 the Louisiana legislature passed the Separate Car Act or law for racial separation of passengers on trains.

In September 1891, a group of black citizens in New Orleans, organized in the Citizens Committee to Test the Constitutionality of the Separate Car Act, decided to express their disagreement through certain public expressions.

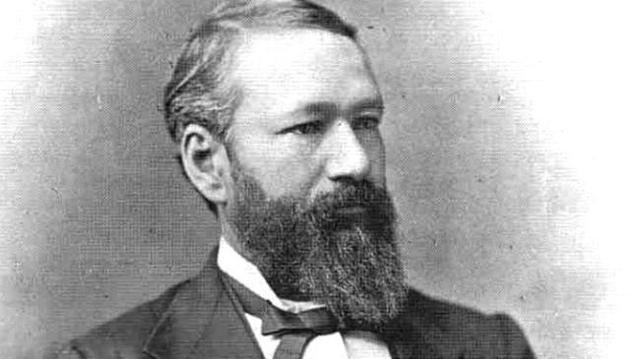

Two years after that act was promulgated, under the shadow of that same Committee and with the advice of lawyer Albion W. Tourgee (who is attributed with the idea that justice has no color), the shoemaker Homer Pessy (1862-1925) boarded one of the white cars on an East Louisiana Railroad Co. train.

The man looked white (“seven-eighths Caucasian and one-eighth African blood”), but he was told to change cars. When he refused, they took him off the train, put him in prison and fined him for disobeying the law: it was exactly what the members of the Committee were looking for.

Taking the issue to court, Pessy maintained that he had been denied his rights under the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution of the United States. But the decision of Judge John Howard Ferguson (1838-1915) did not agree with him when he ruled that segregation on trains was legal. A little later the Louisiana Supreme Court upheld his verdict.

After accepting the case, on May 18, 1896, the Supreme Court would rule on Pessy v. Ferguson. Rejecting the argument of the plaintiff and his attorneys, the justices determined, by an overwhelming majority (7 to 1), that a law that “simply implies a legal distinction” between whites and blacks was not unconstitutional.

As a result, public places separated by race were, in effect, legalized/legitimized. “Separate but equal” would since become a doctrine and a common expression in the vocabulary of Americans. The Jim Crow segregationist laws, typical of the former Confederate territories, had achieved a victory with impacts that would last for decades.

But Homer Pessy and his people had set a precedent: civil disobedience as a factor of change in U.S. political culture. It was the first such action recorded in the history of the Union.

On January 5, 2022, Louisiana Governor John Bel Edwards granted a posthumous pardon to Homer Pessy, the man from the Pessy v. Ferguson ruling.

Both the plaintiff’s and the judge’s descendants joined him at a ceremony in New Orleans, where the pardon was officially signed. The event took place in the same place where Pessy had been arrested 130 years ago.

2

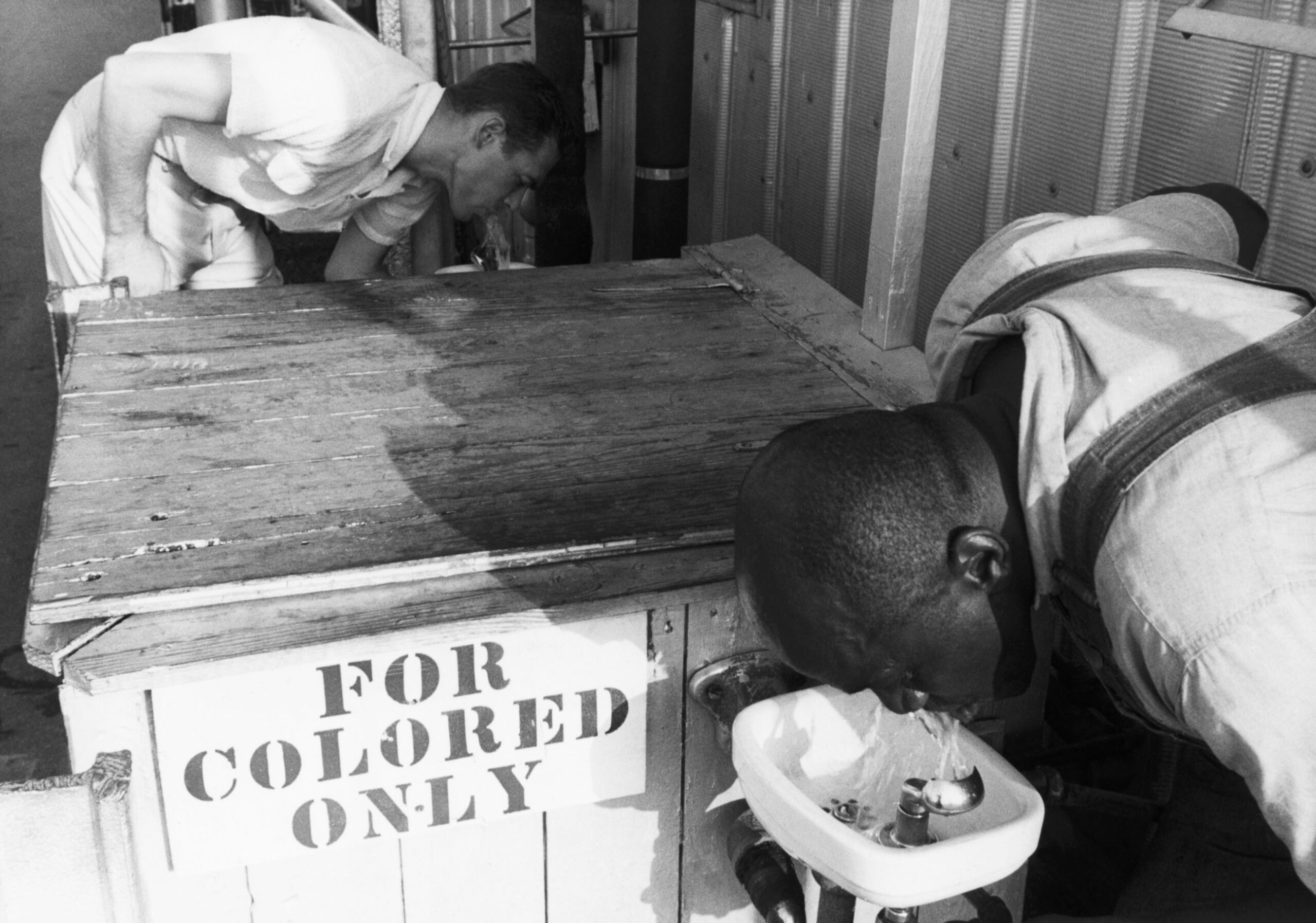

Segregation was a book with many chapters. In the South, white children were taken by bus to their schools, but black children had to walk if their parents could not take them in their own vehicles. Public transportation, restaurants, schools, bathrooms, and even drinking fountains were segregated by Jim Crow laws.

On December 1, 1955, a young African-American seamstress named Rosa Parks was traveling on a bus from Montgomery, Alabama. Noticing that there were white passengers standing in the aisle, the driver asked Parks and other black passengers to give up their seats and stand up. Three of those who were told to do so did, but the young seamstress flatly refused. She was arrested and fined, but accepted the help of the president of the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAAACP), Edgard Nixon (1899-1967), to appeal the conviction and challenge legal segregation in Alabama.

An extremely risky move. They knew perfectly well that they were exposing themselves not only to personal and family harassment, but also to death threats and even classic Southern lynchings. But they bet that her action would have the potential to act as a national spark. Under the auspices of the Montgomery NAAACP, and especially a young Dexter Avenue Baptist Church pastor named Martin Luther King, Jr. (1929-1968), a boycott of the local bus company began.

That boycott lasted 381 days. Progressive protests occurred across the country in restaurants, schools, and other segregated public facilities. They marked the beginning of the so-called sit ins; that is, a form of direct action that involves one or more people occupying an area to protest and promote political, social or economic change. It was a discovery of the alternative movement that would sweep through U.S. culture in the 1960s and 1970s.

On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled that segregation in public education was unconstitutional, overturning the “separate but equal” doctrine in place since 1896 and provoking massive resistance among white Americans implicated in racial inequality.

And on November 13, 1956, the same Court confirmed the decision of a lower court declaring unconstitutional the segregation of seats on Montgomery buses. On December 20, a court order was delivered to end that practice.

The civil rights movement, with significant impacts on U.S. political culture, managed to break the common sense of the time. It was the definitive factor for Congress to decide to approve the Civil Rights Act in 1964, an advanced legislation against all discrimination.

3

In February 1965, the United States began regular bombing raids on North Vietnam. Two years later, in November 1967, the number of U.S. troops stationed in the Asian country was around 500,000 and casualties were increasing. The war was costing the United States about $25 billion annually.

Student protests and sit-ins on university campuses began that same year, when the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) organization decided to express its opposition to the war. They were carried out by young people who, suddenly, validated the word revolution, regardless of how diffuse their meanings sometimes turned out to be.

Revolution of habits, fashions and behaviors. Mental revolution. Sex revolution in the hippie phalansteries — and outside them. Meanwhile, Bob Dylan, Joan Báez, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Crosby, Stills, & Nash, Jefferson Airplane and The Doors would be in charge of establishing in the imagination in a thousand ways the existence of a counterculture that had in peace, love and drugs three of its appoggiaturas. They were musical speeches very different from those heard until then. The Woodstock festival (1969) was its first identity event.

Those protests ended up functioning, ultimately, as another great spark. General disillusionment spread among many Americans as the government recruited more young men for service, and military airports continued to receive coffins with the U.S. flag on them.

Fueled by the work of the media and its correspondents on the ground, who reported war horrors such as the My Lai massacre, when U.S. army troops murdered more than 300 civilians in a village, the movement gained greater momentum, integrated not only by students but also by artists, intellectuals and various protagonists of the counterculture. They all rejected authority and marched against power demanding change, one of the fundamental words of the 1960s. On October 21, 1967, around 100,000 protesters gathered at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington D.C. to express their opposition to the war and the draft.

Arrests and police violence were the norm in protests, until the events at Kent State University, Ohio. The concentrations of defiant students on that university campus led the then Republican governor James Rhodes (1909-2001) to order the deployment of National Guard troops and demand the withdrawal of the protesters, who refused to leave the place; some threw stones at the uniformed officers. Finally, they were shot at. The death toll was four dead and nine injured.

The Tet Offensive began in January 1968. President Ho Chi Minh (1890-1969) and his generals took the war out of the jungles and moved it to the big cities seeking a general insurrection. This did not happen, but the arrow was shot. The offensive ended the political career of President Lyndon Johnson, who was forced to announce that he would not seek re-election. And in October he ordered an end to the bombing.

Six weeks after the offensive began, public approval of the war fell from 48% to 36% and support for its handling fell from 40% to 26%.

The Vietnam War lasted almost twenty years. United States military involvement ended on April 30, 1973 with the taking of Saigon by Ho Chi Minh’s troops. Historian Howard Zinn once wrote that Vietnam was the first major defeat of the American global empire after World War II and that this defeat was achieved by revolutionary farmers and by a surprising domestic protest movement.

To be continued…