It is curious. In Cuban journalism is about anything but journalism. It’s like a black hole. It has the necessary attributes, laws of physics suggest that it should exist, but it remains an accident, a depression indiscernible in the turbulent landscape of the nation.

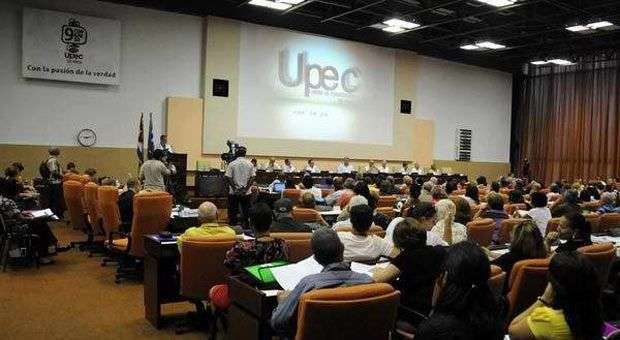

Only custom- extended idleness -makes us see it as a less serious situation than it actually is. Out of the last Congress of the UPEC we can rescue three pieces of news. Diaz Canel himself acknowledged that the main culprit of the mismanagement of the national media was the Party, Raul Garces said “any bump in the road will be infinitely less than the price to pay for another half-century wait for a press that look at ourselves “and Rosa Miriam Elizalde, out of the presentation of the initial results of her PhD thesis, summarized some of the key criteria exposed by journalists in their base assemblies. One of them says that “the recovery of the functions of the media (…) depends on the greater society participation in decision-making, and not the other way around, and this is decided in the political system, not the in the Communication system.”

What makes these views a little more encouraging is not the thorough recognition of the problem. Cuba has done that many times. What makes them more encouraging are the circumstances, the inescapable certainty that today, to get somewhere, society inevitably requires actual participation in shaping the country, and that the party cannot continue to monopolize, lifelong , citizen access to information.

The officers that run Cuban press never understood that for it to be more revolutionary, and, if you like, more partisan, it should be exclusively more press, more gritty and believable, not as pamphleteer and pedestrian, as it is now. It should insist on its social mission, not on the ratification of what is already a false dichotomy. Our more reliable, less pointless comparison is not with the fifties, with the Batista dictatorship, or the Prio and Grau governments, but with what we could be and we were not. A strong country is always measured to the ideal as possible, working with the horizon of its possibility, not with the ruins of which have been erected.

After the Party, however, no one has done more damage to the Cuban journalism than journalists themselves. There is within newsrooms a consensus regarding our status as victims that is downright reactionary. It’s like a collective slap on the shoulder of our esteem, unhealthy resignation, a false redemption, a self-deception, which is, as we know, the worst deceptions. In his farewell letter to Julio García Luis, dean at the time (January 2005) of the School of Communication at the University of Havana, Juan Orlando Perez says: “I cannot continue to teach journalism in Cuba, pretending to believe that my students will have an opportunity to do more than a arid propaganda of a illusion or a lie.”

One, if he has the patience and time, if it is an urgent need, can stay in a media outlet, thinking, hopefully, that he will be able to counter the undeniable, but cannot, in any case, ignore the ground, pretend propaganda is not true, the mirage and, of course, the lie. If something is worth in Cuba are precious few journalists who have leased, with talent and cunning, a small plot, a short column, a minimum space of freedom. For them we have learned that writing well, and writing honestly, is also a political position.

We don’t need gradual changes, advance drills. We need a revolution founding a total subversion of the bases. It is symptomatic. The news of the dead by methyl alcohol was not about dead people themselves, but that we were reporting the incident. From there, from the first note read by Serrano or by someone else on the News of the eight, the rest, let’s face it, was wet rain. So happy we got we forgot or at least try to do what we had to, if we still do.

For the press to play its role, and not to obediently execute superior authorization, was essential to make a detailed investigation of the facts, their causes and procedures, not a series of reports on the diligent attention of physicians to patients. Anyone who believes that this situation was journalism should know immediately that he has been unscrupulously cheating.

I quote the definition of Horacio Verbitsky that pleases my friend Rafael G. Escalona: “Investigative journalism is to spread what someone does not want you to know, the rest is propaganda. Its function is to lay bare what is hidden, to witness and, therefore, to disturbe. Have sources, but not friends. What journalists can exercise, and through them society, the mere right to complain, and as documented and fair as possible. Criticizing everything and everyone. Pouring salt in the wound and pebbles in the shoe. See and say the bad side of everything that the good side is responsible the press office, of neutrality, the Swiss, of the fair between, philosophers, and of justice, judges. And if they don’t do it, what fault is journalism’s? “

The similes are blissful. The Cuban press is like a neocolonial republic. With flag, with shield, with constitution, and without independence. This squandering of this we will bring a forgetfulness of unsuspected consequences. Time, which does not believe in victims or executioners, will continue, and when the future Cubans read the newspapers today, will have the bitter impression that Cuba had everything except country.