There are still broken tombstones and marbles scattered across the floor. In some vaults, the vegetation has won a battle against the cement, but little by little the first Jewish cemetery in Cuba started being rescued and, with it, the memory of this small community on the island.

“I feel a very great peace and tranquility when I visit the cemetery…. For me it’s like being with my mother, my only sister and my nephew,” Adela Dworin, president of the Hebrew Board of Cuba, standing next to a tomb adorned with small stones that Jewish relatives often use to pay homage to their dead, said to AP.

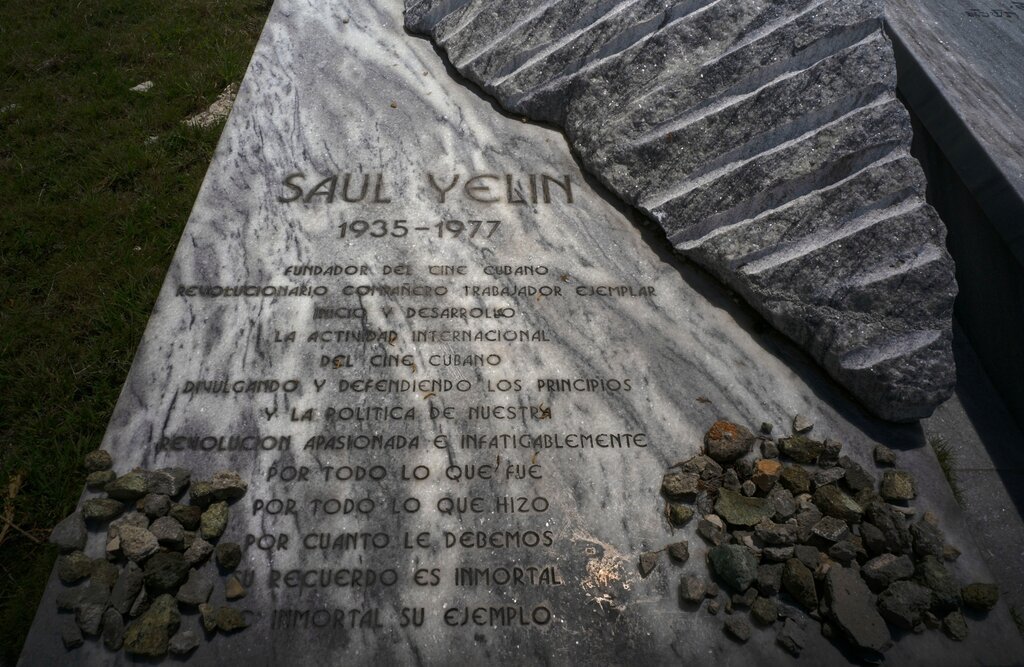

Here and there you can see those rocks―an equivalent of flowers among Catholics―next to the plaques that immortalize the name of a grandfather, a father or an aunt surrounded by Stars of David and words of consolation in Yiddish. Elsewhere, a workers’ brigade polishes the engravings, cements streets or frames a pantheon that was looted.

“The people who came fleeing from fascism during the war are buried here, the ones who founded the community, who bought these lands to make it a cemetery,” David Prinstein, vice president of the Hebrew Board of Cuba, told AP. “It has historical and sentimental value.”

The lands of this Ashkenazi―an adjective that identifies the Jewish people from Central and Eastern Europe―Jewish cemetery were bought in 1906 by members of the first Hebrew society that was created on the island, with people coming mostly from the United States, and it was inaugurated in 1910. Many other families also arrived in the period between world wars, fleeing from the persecution to which they were subjected.

Decades later, one of the Sephardic tradition, native of Spain, was installed in another adjoining plot.

A few years ago, Prinstein and other members of the community estimated the budget to fix the cemetery at 200,000 dollars, but they weren’t able to get the necessary donations. Now it is being restored by the state-run Office of the City Historian.

About to celebrate its 500 years of existence, Havana and the Office of the City Historian are in a real maelstrom of preparations that include the repair of streets and historical monuments to the recovery of documents and valuable sites.

Local engineer Pilar Vega, from the Office of the City Historian, told the press that there are about 1,100 vaults in the cemetery. Of these, about 50 have already been repaired and it is expected that another 150 will be completed this year. An old special room for the purification washing of the body of the dead required by the Jewish rite and another waiting room for families were also repaired.

Vega did not specify how much the state investment will amount to.

Far from the center of the city, the necropolis is located in the capital’s peripheral municipality of Guanabacoa, and it is usually closed to prevent looting, so although the repairs began in the past months, it is now that the result of the restoration can be seen with the paving of the main street and the reconstruction of several of its main installations and monoliths.

“We are not the only problem the country has, there are many places that require the attention of the Office of the Historian, so we are eternally grateful for its interest and friendship to the Jewish people,” said Dworin.

Cuba is currently going through an economic crisis due to lack of liquidity that includes difficulties to pay creditors and suppliers, which usually causes a sort of temporary shortage of some products.

The cemetery has a monument about three meters high that pays tribute to the six million Jews who died in the Nazi holocaust. There lie buried a half dozen soaps made with human fat from the concentration camps.

Dworin, who lost her entire family during World War II, recalled that she was in elementary school in 1947 when the monolith was inaugurated. Her parents left a small town that was then in Poland before the arrival of the Germans, but her grandmother and uncles did not have the same luck, she said.

Some members of the community, especially from the United States, which is usually the one that makes the largest contributions to the community’s projects on the island, eventually offered to help rescue some plots on previous occasions, but not enough to comprehensively deal with the deterioration of the space.

Throughout the years, the Jewish community was not exempt from Cuba’s political ups and downs and many families left the country after the 1959 revolution leaving behind their dead, who in this tradition should not be exhumed unless it is to take them to the Holy Land. The secularism that impregnated the first years of the revolution’s triumph caused some people to disengage and lose their roots.

It was not until the 1990s that Judaism regained strength from the hand of prominent doctor Joseph Miller, former leader of the community, who started bringing together the Jews scattered throughout the island, and even those who were unknowingly Jewish. They reconnected with their past.

Also during those years of severe economic crisis, there was a new emigration of young Jews to Israel through a program of the Canadian Embassy on the island, given the political break between Havana and Tel Aviv.

Cuba and Israel have no diplomatic relations. The former usually rejects the alliance of the second with the United States―they are usually the only two countries that vote in the United Nations in favor of maintaining the embargo on the island―and supports the aspirations of Palestine.

Currently some 1,500 Jews live in Cuba, most of them elderly.

“Families leave and many even forget those who they leave behind here,” lamented Prinstein, acknowledging the deterioration and abandonment of the cemetery during decades of neglect and looting; and who also emphasized that the archives of the cemetery are currently being digitized, which will allow knowing more about its history and that of the community.