Since the end of the Ford administration (1974-1977), and especially during the beginning of Carter’s (1977-1981), there was a certain thaw between the governments of Cuba and the United States.

One of the prevailing perceptions, from the United States, especially in the political discourse and the liberal press, stressed that after the events in Bolivia, with the death of Ernesto Che Guevara and the liquidation of his guerrilla group, Cuba was no longer in a condition to export the revolution. That moment ended with the events of the Angolan war, which paralyzed a rapprochement that led to the creation, in 1977, of the respective Interest Sections in Washington and Havana.

On the other hand, the idea begins to emerge among the emigrants that this was not going to be as short as it was presumed from the beginning, because after two decades the so-called institutionalization process was taking place in Cuba following the imprint of the Soviet Union, after the failure of the Great Harvest and the entrance to CAME. That atmosphere had an impact on many Cubans in the United States and there were two events that somehow marked a change.

First, for reasons of its own, a group of executives and businessmen decided to sit at the table with the Cuban government in what is known as the Group of 75, more moderate people who would then be stigmatized with the derogatory “dialoguers” and subjected to actions that went from intimidation to attacks and bombs. These are the ones who go to the “dialogue with representatives of the Cuban community,” as these persons were officially called in 1978.

The existence of that group, which comprised from former Batista supporters to participants in the Bay of Pigs, constitutes a sign of some diversification of the political spectrum of Cubans, and coincides in time with a second event.

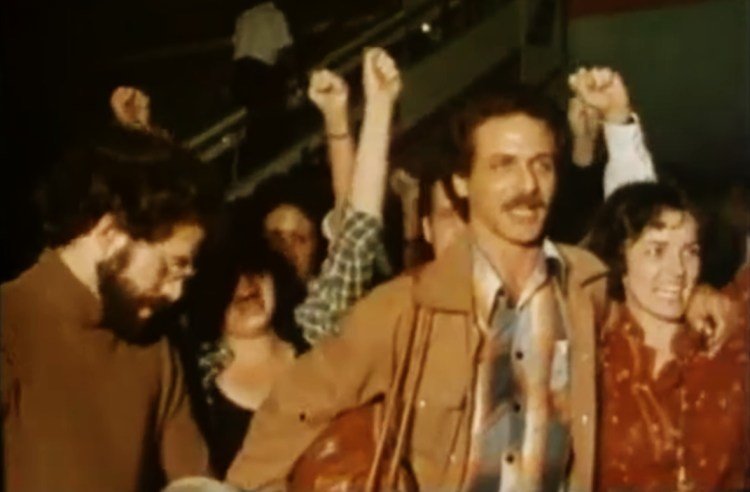

During the 1960s and 1970s in the United States, a counterculture had emerged that had a number of influences on a group of young Cubans who at that time were studying in universities in the heat of the struggles for civil rights, the Vietnam War, mass protests and the appearance of something rather diffuse called “the movement.” All this led to the emergence of organizations such as the Antonio Maceo Brigade and Areíto magazine, in which the figure of Lourdes Casal (1938-1981) played a seminal role.

It was the first time that there was direct and massive contact between both shores due to the Cuban State’s policy of allowing the visits of those who had left, on the condition that they not be involved in activities against the system. The trips of Cuban-Americans produced a polyvalent internal impact that went from rejection to acceptance, as evidenced by the documentary 55 hermanos, by Jesús Díaz, or one of the stories of Mujer transparente, by Marisol Trujillo, in which the reconnection of two friends in a hotel in Havana is narrated. The “worms” (as those who left Cuba were called), suddenly became butterflies, a social perception not without irony and Cuban jokes.

However, the initial official treatment they were given was weighed down by a problem: they were tourists.

At first the members of the “community”―that new word in the national idiolect―had to stay in hotels and buy in stores specially enabled for that purpose, the starting point of a culture of consumption that, as Lezama would say, would spread like wildfire over the social fabric. Sanyo fans, acquired by relatives in the stores for diplomats, joined the Soviet Orbits in homes. The portable Sony radio-recorders allowed listening to things as dissimilar as the cassettes of Silvio Rodríguez, Celia Cruz’s salsa and jokes by Guillermo Álvarez Guedes, between meals and drinks, glancing at family ties.

The title of an anthology of Cuban literature, published by Edmundo Desnoes in 1984, which included authors from within island and from the diaspora, summed up as few the problem: Los dispositivos en la flor, a phrase that the anthologist borrowed from a poem by Cintio Vitier. The book was virulently bombarded in and out of the island, as corresponds to a polarized culture in which passions play an important role. A reminder of what is being recycled right now, but with much less level, is not temporary but genetic.

On the other side, the Diccionario de Literatura Cubana, of the Institute of Literature and Linguistics, a work that took too long in coming out, marked the territoriality of what is Cuban, limiting the concept to the writers inside and excluding those who had left, an idea that also took too long to be removed, and certainly not entirely until today.

The social effects of this logic of contact have been studied. Frequently it has been made responsible for constituting the cause of the Mariel events, one of the most traumatic on both sides of the Strait. The basis of this argument is based on the visitors’ psychological-cultural impact on the islanders, a unilateral formulation that obliterates the internal problems generated by Cuban socialism itself and the presence of a component of inherited and unresolved marginality. One of the reasons for Mariel, but at the same time the boom, cannot be reduced only to that.

At the end of the 1970s there is a whole accumulation in Cuban society that serves as the basis for that stampede of about 125,000 people. The failed economic policies and voluntarism, criticized by the First Party Congress, in 1975, together with factors such as the drop in sugar prices, constituted the fuel due to the effects on daily life, only cushioned later, when the so-called “little markets” allowed Cubans to enjoy relatively acceptable levels of consumption with their monthly salaries, even though the quality of the products could never compete with that of their western equivalents.

The Mariel exodus was basically a combination of internal circumstances with the effects of the privileged reception of illegal immigration, endorsed by the Cuban Adjustment Act. The “community” visits were, in any case, a shutter―and not the cause. To endorse the opposite would be equivalent to blaming the sofa and not the lover.

But the ice of solitary confinement between the people on both shores had been broken. That was, at the end of the day, what was most important.