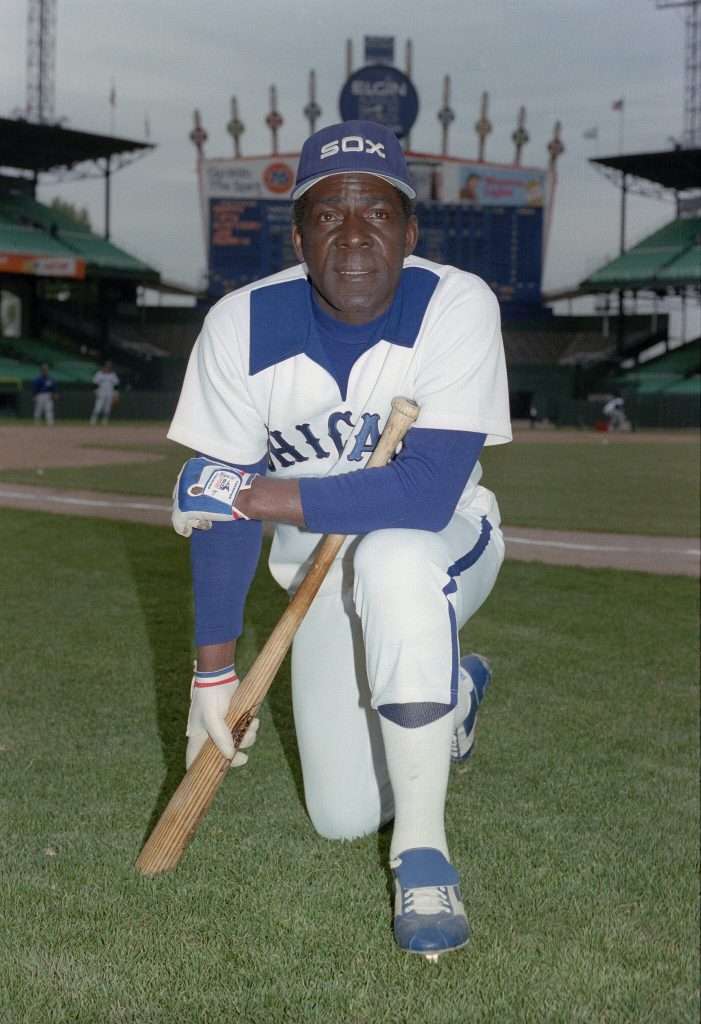

Bob Kendrick (Crawfordville, 1962) never saw Orestes Miñoso play in his golden stage in the Major Leagues. That Afro-American boy was only two years old when the “The Cuban Comet” hung up the spikes in 1964, after having surpassed the barrier of 2,000 hits, 1,200 scored runs and 1,000 RBI, in addition to being the only Latino in history with more than 600 extra-base hits and fewer than 600 strikeouts.

Kendrick’s early memories of Miñoso in the field are somewhat vague. He remembers that, as a teenager, something of a stir was created in Chicago over the return to the diamonds of a veteran who would become the second player in history to participate in five different decades, but that event ended up being something symbolic.

However, the name of Miñoso was etched in the mind of Kendrick, who decades later had the unique privilege of sitting next to the Cuban legend and discovering there, first-hand, the true significance of being the first black Latino in the Major Leagues and one of the most influential players in the history of the Chicago White Sox.

“I can’t even count the number of times that he and I sat in the conference room adjacent to my office, just talking baseball and talking about life and the joy that he had for this game,” Kendrick recently told The New York Times.

Thrilled that my friend & @whitesox legend, Minnie Minoso, was finally selected for induction into the @baseballhall! Wish it had happened when he was still alive. Can you imagine the the energy and excitement that Buck O’Neil & Minnie would have brought to the ceremony? @MLB RT pic.twitter.com/DApma9pTKt

— Bob Kendrick (@nlbmprez) December 10, 2021

Almost 60 years old, the current president of the Negro Leagues Museum is now very clear that Miñoso paved the way for hundreds of Latino players to have the opportunity to show their talent and shine in the best baseball in the world, something unthinkable in the middle of the Last century.

Perhaps that is why, knowing exactly the magnitude of the legacy of the great Mr. White Sox, Kendrick cannot understand why it took so long to open a space for him in the Cooperstown Hall of Fame, the temple to which he belongs and to which he should have entered while alive.

“It should have happened when he was still with us, and I know how much it meant to him,” Kendrick assured, endorsing something that Miñoso himself had said a few years ago in an interview with Christina Karl: “I don’t want that to happen after I die. I would like it to happen while I’m alive, I want to enjoy it.”

Unfortunately, that was not so, despite the fact that Miñoso, as Kendrick put it, he “was one of those bridge builders, and those who become bridge builders in our society have a very special place.”

Miñoso’s legacy was distorted too much after his return to the Major League diamonds in 1976 and 1980 to become the second player to participate in five different decades, a picturesque detail that was born in the mind of White Sox owner Bill Veeck — the same one who had made him debut in Cleveland in 1949 — but not decisive in the career of an athlete.

That eccentricity of Veeck cost Miñoso, who was not appreciated by the voters of the Baseball Writers Association of America (BBWAA), to the point that they never gave him even a third of the support necessary to enter Cooperstown.

The same happened later with the Special Committee of the Negro Leagues or the Veterans Committee, who ignored his numbers and his impact on the game.

Various specialized websites argue that voters “let Miñoso pass” because they did not see him play or because they only remember his last games when he was more than 50 years old in 1976 and 1980, which, of course, were disastrous beyond the media paraphernalia they provoked. Those, however, are empty and meaningless excuses….

Voters have enough material to study the careers of players they did not see directly on the diamond. What’s more, with all the available documentation they should be able to assess the performance of the players fairly, even those who did not win titles or individual grand prizes.

Miñoso is one of those cases: he participated in 13 All-Star Games and won three Golden Gloves, but he was never in an MLB World Series (he participated in and won one in the 1947 Negro Leagues with the New York Cubans), nor did he win Rookie of the Year or MVP in his 20 seasons in the Majors

However, we must look at things in detail and not be left with only the first impression of what the biographical sheets and statistical records show us.

For example, in 1951 Miñoso finished second in the race for the American League Rookie of the Year, an award that the Yankees’ Gil McDougald won, but if we study in depth the performance of both, it will not be difficult for us to realize the injustice committed. The numbers leave a very clear evidence:

* Miñoso (batted .326, with an on-base average of .422 and slugging of .500. He batted 173 hits, scored 112 runs, drove in 76, stole 31 bases, received 72 walks and struck out 42 times. He hit 34 doubles, 14 triples and 10 homers, for a total of 58 extra-base hits)

* McDougald (batted .306, hitting .396 and slugging .488. He batted 123 hits, scored 72 runs, drove in 63, stole 14 bases, walked 56 and struck out 54 times. He hit 23 doubles, four triples and 14 homers, for a total of 41 extra-base hits)

Something similar happened in 1954 in the dispute for the Most Valuable Player of the American League. Miñoso finished fourth in that race, behind Yogi Berra (Yankees), Larry Doby (Cleveland) and Mexican Bobby Avila (Cleveland), although in several departments he was superior to all three.

* Miñoso (batted .320, with an on-base average of .411 and a .535 slugging. His OPS was .946. He had 182 hits, scored 119 runs, drove in 116, stole 18 bases, walked 77 and struck out 46 times. He hit 29 doubles, 18 triples and 19 home runs, for a total of 66 extra-base hits)

* Berra (batted .307, hitting .367 and slugging .488. His OPS was .855. He batted 179 hits, scored 88 runs, drove in 125, stole no bases, walked 56 and struck out 29 times. He hit 28 doubles, six triples and 22 homers, for a total of 56 extra-base hits)

* Doby (batted .272, with an on-base average of .364 and slugging .484. His OPS was .847. He batted 157 hits, scored 94 runs, drove in 126, stole three bases, walked 85 and struck out 94 times. He hit 18 doubles, four triples and 32 homers, for a total of 54 extra-base hits)

* Ávila (batted .341, with an on-base average of .402 and slugging of .477. His OPS was .880. He had 189 hits, scored 112 runs, drove in 67, stole nine bases, received 59 walks and struck out 31 times. He hit 27 doubles, two triples and 15 homers, for a total of 44 extra-base hits)

These may not be conclusive proof, but they show us quite clearly the superiority of Miñoso, whose greatest sin was to remain in his golden years as a member of second-rate teams; besides being black and succeeding in a scenario theoretically reserved for whites.

Yes, because no one can doubt that the Cuban experienced the consequences of segregation firsthand, especially as a star in the city of Chicago, one of the epicenters of the African-American community in the United States.

Miñoso himself said that in 1951 a team always insulted him. “They used foul language and referred to my race. I think they were trying to scare me,” he reported to The New York World–Telegram and Sun.

If overcoming all this, shining on the field alongside the great stars of the time and then contributing to the development of future generations were not solid enough arguments to open the doors of the temple of the immortals in Cooperstown, then I do not know what else was needed.

Despite disappointments with the Hall of Fame, Miñoso never turned his back on his sport, nor on the Latino community that bowed at his feet, nor on Chicago, where Mr. White Sox was, is and always will be, as former U.S. President Barack Obama said after his death.

Far from betraying, Miñoso insisted on teaching everyone about the need to respect baseball and its fans. “Fall in love with the game. Do everything beautiful for the game, for the people and for the country you represent. That’s what I want everyone to do,” he said a few years ago.

Many have followed that message to the letter and have promised to protect his legacy until the end of time, such as the stellar pitcher from Pinar del Río José Ariel Contreras, who considers Miñoso a legend, an example, an inspiration, “our Jackie Robinson.”

This is an excellemt tribute to a great player and fine human being.

As a child in Chicago I was a diehard Cubs fan. In adolescence I was an Indians fan (Bill Veeck was my best friend’s uncle and I got to sit in the owner’s box when the Indians came to town and I could root against the hated Sox).

Through all that I loved Minnie Minoso. About time he got in the Hall.