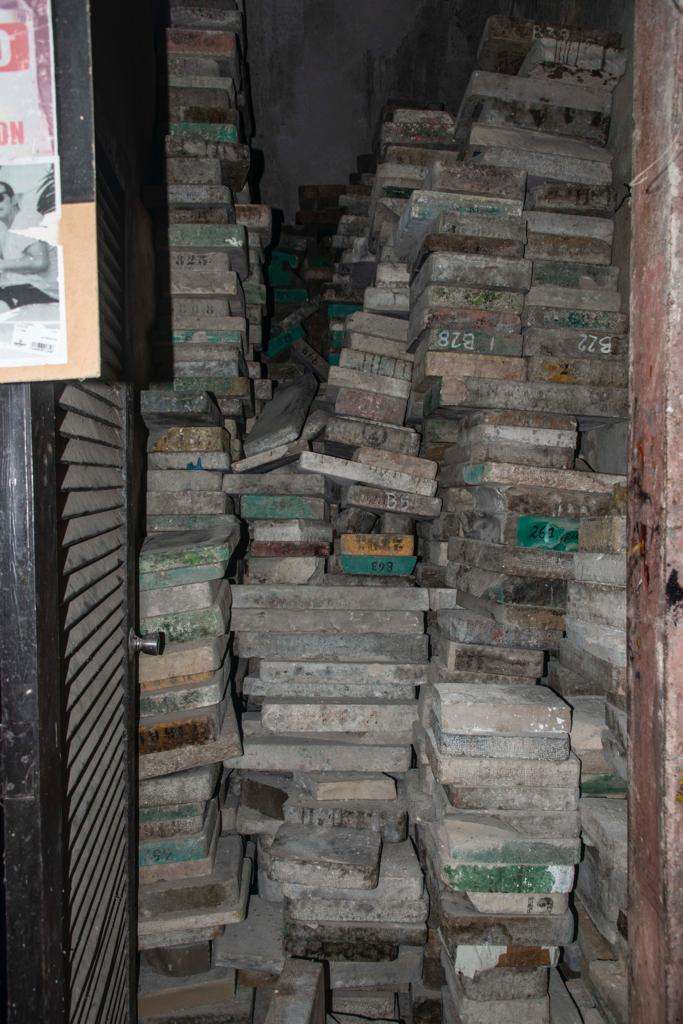

A surprising find occurred recently at the Engraving Experimental Workshop of Havana (TEGH): a batch of 4,000 lithographic stones stacked in a dark and narrow space in a corner of the workshop.

The stones, with their stamped inscriptions and images, had been there for decades. It was the photographer and researcher Julio Larramendi who, looking for a specific stone to illustrate one of his books, noticed the narrow opening in the wall that led to the treasure.

After this, a process of cleaning and identification of the images engraved on their surfaces, as well as their possible authors, began. The prints were studied and classified. Some sixty students from the Information Sciences course at the University of Havana and the same number from the Workshop School of the Office of the City Historian carry out these tasks.

Duly protected and under the supervision of experts, these young people have extracted the stones one by one to move them to a nearby gallery, always inside the Workshop, an institution that has preserved this heritage for all these years.

The students of the Faculty of Communication begin the extraction and transfer of the stones.

This singular team has processed two thousand pieces. Each one has gone through three phases: definition of the state of conservation of the stone and its inscription; washing and scanning of the stone and the stamp drawn on it; and, finally, classification (for example, those that are considered artistic drawings are immediately delivered to the TEGH).

Once this process is finished, the stones are returned to a provisional space within the Workshop until it is decided what to do with them. In a month or so, the work should be completed.

This process was supported by software developed at the Faculty of Information Sciences that allows saving the data obtained and identifies the student who did the work. Subsequently, research can be carried out on the topics represented in the stones.

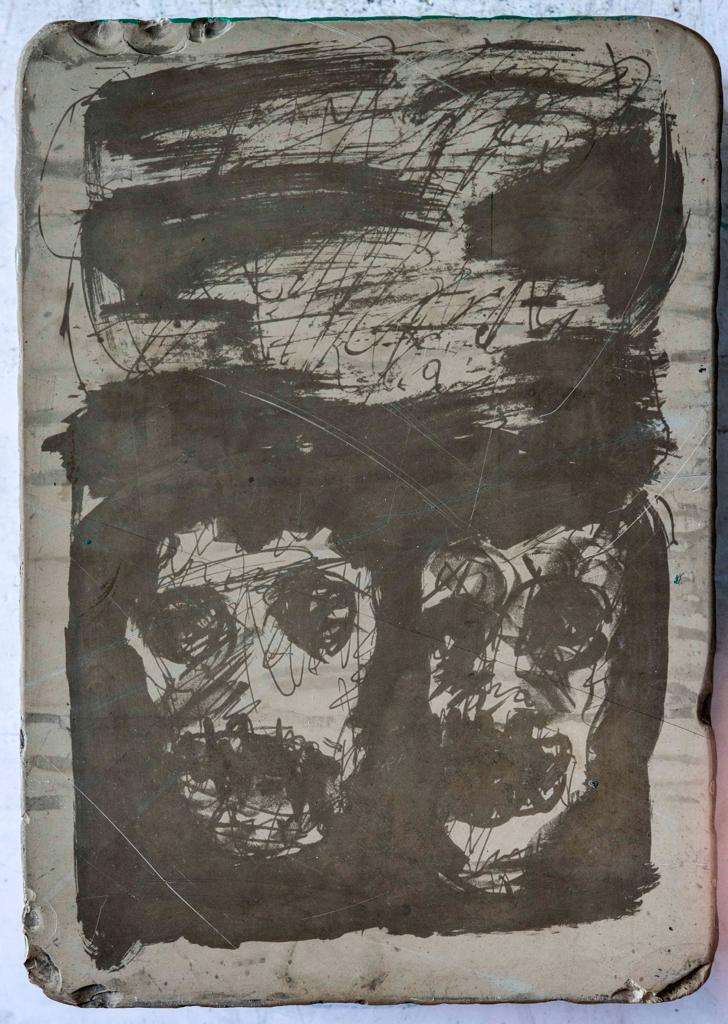

The pieces have enormous heritage value. Among them stand out stones with the signature of Roberto Matta, Antonia Eiriz, Víctor Manuel, Manuel Mendive and Antonio Canet, among other recognized artists.

In addition, others no less valuable pieces reveal their use for commercial purposes associated with the tobacco industry, first of all, and with beverages and liquors, fruits, perfumery, pharmacy, and chocolates.

This could be the prelude and foundation for various exhibitions, books and other actions of artistic and cultural value. It could even revive an old dream: the creation of a museum of Cuban engraving.

Stone stamping in Cuba had as antecedents the engraving on wood and metal in the 18th century. Then the lithographic technique arrived from Europe, associated at first with the musical development of the colony. Sheet music and other musical prints were the first use for these prints. Then came the rural and city landscapes, the portraits of colonial personalities and the scenes of types and customs of insular society. Lithographic art has left us excellent books, today classic pieces of our literature and visuality.

According to various studies, a French miniaturist painter who had lived on the island for years, Santiago Lessier Durand, established the first workshop in Havana in 1822. From then on, a solid lithographic tradition began to develop.

This is confirmed, in her book La memoria en las piedras (Ediciones Boloña, 2001), by the renowned researcher Zoila Lapique Becali, Honorary Member of the Academy of History of Cuba and an authority on the subject.

Subsequently, the lithographic activity was modernized and industrialized in order to produce the largest number of copies of the prints for commercial purposes.

This is how the first half of the 20th century went. With the political and cultural dynamics that began with the triumph of the Cuban Revolution, it was a matter of time before a Workshop for artistic engraving was created.

In July 1962, the TEGH was founded, located today at the end of the Callejón del Chorro in the Plaza de la Catedral, Old Havana. This emblematic institution began to work with disposable equipment from the former Havana Lithographic Company. During its existence, it has gone through several stages in terms of development, but it has always been the epicenter of the creative work and exhibition of engravers in any of the techniques. Before settling in its final location, the Workshop was in other buildings, including the Palace of the Marquis of Arco.

There is a version of its history that speaks of the fact that its presses, plates and stones were in serious danger due to the defensive fever that prevailed in the first revolutionary years. Lithographic stones were used at this time to create parapets and barricades. The machines would be melted down for the same military purpose, in the face of continuous aggression and threats from the United States.

It is also said, in this version, that Che Guevara and the poet Pablo Neruda — the latter visiting Cuba and attentive to the claims of the local engraver José Venturelli, a worker at the Workshop — intervened jointly in favor of the Workshop not becoming extinct.

In the institution’s six-decade history, the best Cuban engravers and many artists of other nationalities have passed through its machines and produced splendid pieces of art, while exhibitions and events have been held that have exalted the tradition of engraving on the island.