These photographs are notes in a process that does not end. The beginning was Ana and Mabel’s hands on the yellowed pages of the Verde Olivo magazine with interviews with soldiers returning to Cuba after long years in Angola.

“As much information as possible must be given to locate an image. Because maybe the name is not there, but the place or date appears: ‘he was in the Kifandongo battle,’ or ‘it was in November 1975.’”

I was in the Archive of Verde Olivo magazine, the official organ of the Revolutionary Armed Forces, filming part of its photographic collection for the documentary Días de diciembre, about our memory around the war in Africa, about the imprint of an era. Ana and Mabel told me about the structures of the archive that stored these images; but the gesture of their hands was different from order and logic. A gesture of affection. For both of them, in the faces of the soldiers, in the sadness of the relatives before the funeral urns, they were also there, young and dressed in olive green. Their memory was inseparable from the “representation of an era in the image.”

Días de diciembre / December days (2016) from Carla Valdés León on Vimeo.

Years later, in Holguín, I met María, in charge of the Provincial Historical Archive, who explained to me — with pleasure — the organization of the work there, its documentary collections, the history of the building, and her place in it. I was researching for what I thought was going to be a documentary about “the archives of the Revolution.” I review my notes written during that conversation, in which the data is mixed with her phrases in quotation marks, written down quickly, so as not to forget them. I reproduce a part, and add my notes, today:

There are gaps in all stages, but where there are most is in the revolutionary period. We have lost a large number of documents from the sugar industry due to mismanagement. Many were incinerated in the boilers. They became pulp. When the Revolution came, the documentation of the Republic was thrown into the hallway and remained there until a historian rescued what he could. Everything smelled of reaction, of bourgeois.

The Holguín Archive’s funds go back as far as 1737: from notarial protocols of the Colony to the minutes of the People’s Power Assembly from five years ago. According to my notes, of the 26 workers, 20 were women, the vast majority elderly. It is a relationship that is repeated in other archives that I later visited: National Historical Archive, Film Archive, Office of the Historian of Havana, Provincial Historical Archive of Matanzas, Verde Olivo, Bohemia Photo Library, ICRT Heritage Archive. Among all of them, María leaves me stunned between the shelves when she tells me:

Those of us who work in this know what the document feels like, because what you care for and preserve is like the child you have fathered. When a document is lost it is like having my arm cut off. It has to hurt in the flesh. All people, as we have a family or blood relationship, have a relationship with documentation.

This piece of memory that María cares for is part of her body; it is as much hers as her arm, her leg, or her family.

Inés reminds me of the primary school teacher who taught me how to write. She is older, thin and upright in character. She is the head of the Restoration Department of the National Archive of the Republic of Cuba. On the day of our first meeting, she was told that she was going to receive a medal for her work on that same day; but she did not go to the event. Inés cares little about medals and certificates.

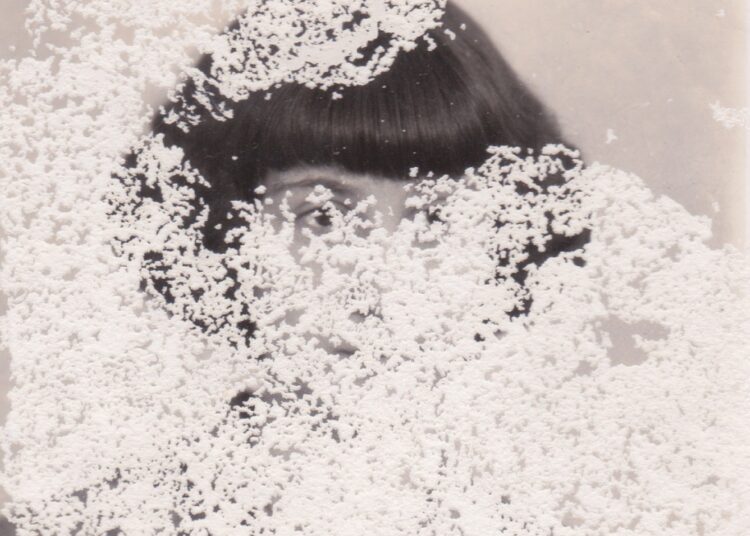

She has brought back to life many “old papers” in that department on the ground floor of the National Archives. She has been there for so many years that the place no longer seems like an office, but rather a house where she receives visitors (me) and cares for the sick (the Constitution of 1940, the correspondence of José Antonio Saco….) On a table, a vase with still life, a sheaf of documents, work instruments, and the charcoal portrait of a girl from another era who arrived one day and stayed there. Nobody knows who she is, but everyone who works with Inés decided to leave her as company.

From how much she told me that day, I remember this. She tells me about when she was in charge of restoring José Martí’s correspondence that today is kept in the Historical Affairs Archive of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Cuba. I wanted to know what Martí said in his letters, what he wrote about if she read them all. Inés doesn’t remember the words, she has forgotten that, she tells me with a gesture of her hand in the air that seems to erase the inconsequential. But she confesses a secret to me: after many letters, she discovered that she could know, or sense, Martí’s state of mind based on the shape of his handwriting. And she talks to me about emotions: joy, sadness, euphoria, love, fear.

She would never have thought that my spirit (the anima) could be translated into calligraphy. Inés knew how to find this life in the Apostle’s letters and, without knowing it, perhaps she has come to know him better than any historian or biographer. Inés is a friend of José, whose last name is Martí, of his cast iron handwriting on paper.

In another of my notes, I find this quote from Rosario Castellanos where she says that memory is, “perhaps more than anything else, the first ransom we pay to the most elemental form of death: oblivion.”

My maternal grandmother was called Martha and, in addition to being my grandmother, from a young age she became the face of many soap operas and national television programs. In her career as an actress, she played the lady in distress, Juliet, the mother of the internationalist fighter, the teacher of the underground struggle. Off-screen, she was a militia member, a delegate to cultural congresses, a member of the Federation of Cuban Women, and sent to diplomatic missions.

Before turning 85, she was diagnosed with advanced lung cancer. The cigarette was always mandatory between programs, between one take and another. “You have to die of something,” she tells me while she separates her family photos, the ones she inherited from her mother, and the ones that portray the family she had with my grandfather. They as young people, their children, us, their grandchildren. Some will be for her son and others for her daughters. Some briefcases are separated. She tells me: “I have saved this for you.”

My paternal grandmother’s name is Julia Nereyda and she was born in 1930, in Las Vegas de Sagua, a countryside in the center of the country. Her grandparents were Spanish emigrants. She, the daughter of farmers, worked and learned about the land and the life cycles of a house. After the Second Agrarian Reform Law, the farm on which she lived with her husband and her children was reduced. The family moved to the city and kept only a small piece of land used by the State. Their children finished growing up there. She continued attending to the family cycle with her grandchildren until her memory began to abandon her.

In her old age, she has returned to being the girl who grew up in the countryside, so she remembers the guanajos, sunsets, and Spanish grandparents. Her story goes forward and into the past. My grandmother is not tied to any chronology. Sitting in the armchair in the living room, the street under the sun, the iron gate, the plantain bush that we see outside, become a large pasture for her.

The photos of my maternal and paternal family, my family archive, were saved hidden in my grandmothers’ closets. In suitcases, cardboard boxes, or cookie tins. That of one of them organized and catalogued; the other, with a musty smell and no apparent order, mixed with sewing threads. Both, with the mediation of their daughters, allowed me to inherit this archive. And, with the help of a friend, I took it out of their closets and put it in mine. I wanted to make a film with their heritage. And I did it, with more friends.

Family trees are the map of a family, its ancestors, and its descendants. If this filiation is narrated from the succession through the male line, it is called bloodline. On the other hand, if the narrative is guided by female surnames, offspring with a female name are called the navel line. And I think, I note, that each knot of this line is nothing more than a pact of love and care.

Now that I’m out of the house I grew up in, I miss that closet where I kept all the boxes, my family archive. Sometimes I go back to the photos I took before I left to remember where I left each album, the VHS cassette with the end-of-the-year videos. When I can, I ask my family to find a particular photo and send it to me, or a friend to bring me a piece of it: a tape of my grandmother’s voice that I need to digitize with technology I only have here. Excuses.

I inherited from my grandmothers their memory kept in the back of the closet, and this — writing and imagining films — is my way of taking care of them. Just as Ana, Mabel, María and Inés care for what we inherited before, collectively, in the nation’s archives. An archive is not just custody. It is like caressing a loved one: an act of love.

Mother Line_Trailer_VdR Market from Carla Valdés León on Vimeo.