By Carlos Batista

During the colony, barrels (toneles) loaded with wine from Spain arrived in Cuba. Now they arrive empty, made of white oak, discarded by the whiskey industry, ideal for aging Havana Club rum. But finding a barrel full of Cuban art in Canada is a real find.

This is how I found Antonio Eligio Fernández (Tonel), a 65-year-old visual artist that many of us began to admire in the distant 1970s, when he began his early career as a caricaturist, artist of posters and other early works, even before graduating in History of Art in 1982.

Currently, Tonel’s art seems to have no limits or borders: he has a vast work of drawings, paintings, sculptures, installations, which go hand in hand with constant academic activity in different universities in Cuba, the United States and Canada, as well as a curator and critic.

“Tonel’s work stands out for its acute ability to satirize and criticize sociopolitical aspects of Cuban reality. Through a visual language that combines humor, irony and a provocative aesthetic, Tonel confronts issues such as bureaucracy, censorship, and economic difficulties,” Cuban curator Patricia G. Kasaeva, founder of Haba Gallery, in Barcelona, told us.

Tonel is one of the almost 20,000 Cubans who reside in Canada. In 2000 he settled in the United States for personal and professional reasons. Starting in 2005, he and his wife found spaces at the University of British Columbia (UBC), in Vancouver, Canada, where they still live.

Now, when the Cuban Parliament will approve new emigration and citizenship laws, Tonel does not consider himself an emigre, since he has no political or economic motivations.

Cuba in the soul

“In all that time, I have maintained close personal, family, friendship, and professional ties with my compatriots in the archipelago and with my country. I have never felt like someone who is totally far away or outside of Cuba, I mean, on a spiritual, emotional, affective level,” he responded to Desde las dos Aceras.

However, “I understand that at times my relationship with the homeland is mediated, to a certain extent, by geographical distance, and by other distances that cannot be measured in kilometers or miles.”

Even so, Tonel does not escape that occasional fever of those who live far away. “At times I have felt homesick for being away from my homeland, although this is not a permanent state of mind,” he admits.

“It is important to reflect on what inspires our nostalgia: are we motivated by the idealized memory of the country or city we miss? Or do we miss the real place (and not the place of memories), the one that continually changes and evolves until it becomes something somewhat removed from our experience? Almost certainly, I think, we miss both: the ideal, which at times can seem almost perfect in memories, and the real one, with its palpable lights and shadows,” he points out.

He considers that his “vision of Cuba is paradoxical. On the one hand, it is a familiar place, that I know very well, and which makes me feel at home. On the other hand, it is sometimes an unknown place, with characteristics that are foreign to me and do not conform to the familiarity I mentioned. Although I have regularly and from every point of view maintained direct contact with Cuba, it has happened that a certain distance is established, gaps are created in mutual knowledge.”

“Today’s Cuba is a place of paradoxes, contrasts and inequalities that are increasingly better outlined. It is my opinion that a considerable part of the changes that have occurred in Cuban society, particularly during recent decades, have brought negative consequences that affect society in a general and profound way.”

For Canadian curator Keith Wallace, “most of Tonel’s work consists of drawings, and most of them involve some type of self-portrait; sometimes it’s obvious and sometimes it’s not. His self-portrait functions as an alter ego, and his rendering of it on paper offers Tonel a means of expression that he would not otherwise be able to use in his everyday social life.”

Wallace points out that the work of Tonel and other contemporary artists was centered on Cuba, especially in the 1980s and 1990s, with the disappearance of the Soviet Union and its consequences for Cuba with the so-called Special Period.

“But his interest in Cuba is not based on nationalism, it simply happened to be the place where he lived, and that particular period of history impacted his daily life and his understanding of the rest of the world,” says the Canadian.

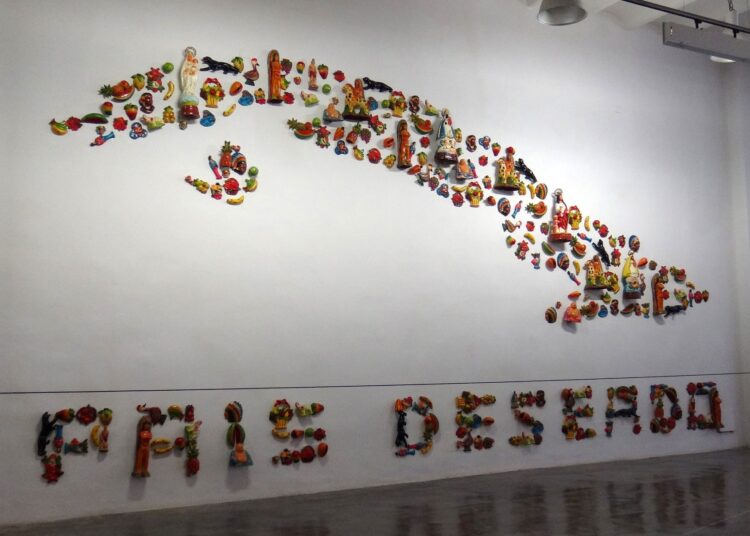

Tonel, for his part, told us that “in an important part of my work, Cuba has occupied and occupies a fundamental place. I think above all of my installations and drawings inspired by the particular circumstances of Cuba: its history, its culture, its geography, its place in some of the largest geopolitical conflicts in the second half of the 20th century.”

Furthermore, “my perspective of the world and history is partly conditioned by my formation in Cuba, at the same time as influenced by my experiences living and perceiving the world from other places, such as the United States or Canada.”

The German-Uruguayan essayist and critic Luis Camnitzer met Tonel in 1983 and they became friends.

He has said that he visited Havana in 1994. “The effects of the Special Period, the economic misery resulting from the collapse of the Soviet Union, were visible not only in the deterioration of the city but also in the appearance of the Cubans, my friends included, back then.”

“I could see and comment in those moments that I could distinguish the corrupt from the ethical by their weight. The corrupt ones were still plump and looked very good. Tonel, on that visit, looked extremely thin and bad. But his humor and lucidity had not changed,” he added.

Political humor is very present in Tonel’s work, where even the classics of Marxism appear.

But “instead of locating himself in an ‘I’, Tonel instead positions himself in a ‘we’ and thereby seduces the public to analyze himself along with him. The artist no longer gives instructions. This change gives Tonel’s work a quality that has no artistic importance but, more importantly, is ethical,” says Camnitzer.

In that sense, adds Kasaeva, Tonel’s pieces “invite us to a deep reflection and questioning of the status quo. Tonel’s ability to mix elements of popular culture with historical and political references gives his work a global empathetic openness, which is fed by icons of a Cuba with Soviet remnants.”

Havana always

Tonel was born, raised, studied, and loved in Havana.

“No corner of the world remains static over time. However, in my modest opinion, the most noticeable changes in Havana, especially during the second and third decades of the 21st century, go beyond the normal ups and downs that have historically affected this beautiful and unique city.”

“The capital of Cuba is an extraordinary city, which despite everything retains much of its secular vitality and dynamism. It is still a photogenic and attractive city, but the truth is that time and circumstances have dulled much of its historical brilliance, and conspire against its indisputable beauty,” he adds.

He believes that “there will be many valid reasons and explanations for this deterioration, although the most important thing, explanations aside, must be the recovery and safeguarding of a heritage that belongs to all Cubans.”

________________________________________

*Text taken from the author’s blog, Desde las dos aceras. It is reproduced with his express permission.