Some barriers are difficult to break, whether due to social stereotypes, prejudices, or stubbornness. To confirm the statement, it is enough to look at Cuban sports and the delayed approval of the official and “massive” practice of weightlifting, wrestling, or boxing among women.

The saying seems tailor-made: “you shouldn’t push your luck.” That has been the reality of these disciplines, a constant attack by Quixotes against windmills, until in 2006 the highest authorities of the nation, including the until then reticent Federation of Cuban Women (FMC), gave the green light to make official the extensive practice of the first two specialties.

It was a flag lowered as if in the middle of the Formula 1 circuit, because in a few months the Central American and Caribbean Games in Cartagena de Indias, Colombia, were looming, which logically were attended with practically improvised teams.

In the case of wrestling, I remember that a group of girls came to the fore, coming from judo, with as much audacity as desire to impose themselves, because at the time of the change of modality, they were second or third figures on the tatamis, where the rivalry was huge and the options of assuming the title in their divisions very reduced. We are talking about the pioneers Catherine Videaux, Lisset Hechevarría, Yaqueline Stornell, Yamilka del Valle, Sheila Espinosa, Yaritza Abel, and Cándida de Armas, to name the highest-caliber ones.

In their debut on Colombian soil, Abel (63 kg) and Hechevarría (67) won titles, while Espinosa (55) won silver and Del Valle (51) and Yagnelis Mestre (59) won bronze and rounded out the resounding haul of that international debut.

Thus they went through a cycle that saw Lisset Hechevarría (72 kg) emerge as the first woman capable of winning a medal at the continental level, with her bronze at the Rio de Janeiro 2007 Pan American Games.

The emergence in the Olympic context would take a little longer. It would not be until London 2012 that Catherine Videaux (63 kg) could embark on representing the girls, with an eighth place that could be considered successful given the quality bar of an event under the five rings.

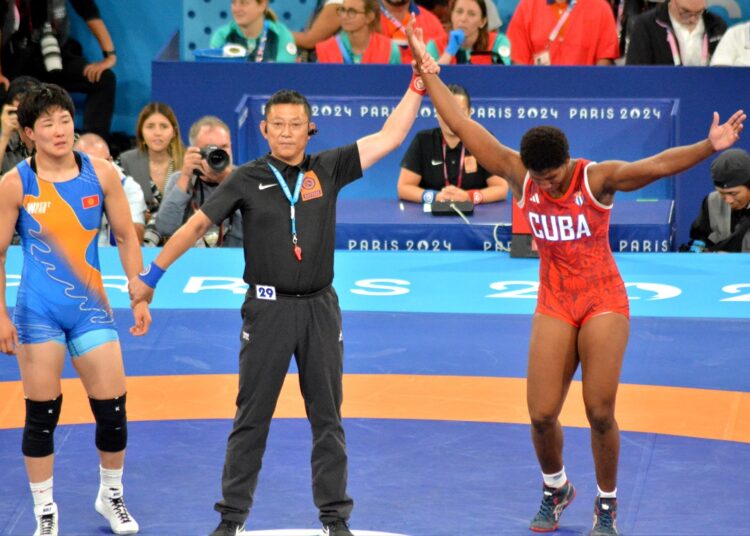

Already immersed in the “Olympic sauce” and with the clock ticking, it was time to disembark on the mats of the Champs de Mars Arena, where on August 7, 2024, Yusneylis Guzmán, the 50-kg “La Chiqui,” finally sounded the clarion call.

With tons of unsuspected sacrifice, the accurate guidance of the experienced coach Filiberto Delgado and 100 fortuitous grams decreed the disqualification of the Indian Vinesh Phogat and the advancement of the Havana athlete to the title discussion. Guzmán emerged as the first gladiator of the largest of the Caribbean islands capable of winning a medal in such a lofty panorama. Her epic silver medal was followed four days later by the bronze of her teammate Milaymis de la Caridad Marín (76 kg).

An 18-year journey from 2006 to the City of Light, different battles and walls that were belatedly torn down to witness the splendor of the medals.

Two aces inside

Although the influence of various variables has increasingly diminished the firepower of the Cuban sports movement, there are still athletes who prove the traditional drive and potential of our forces. Yusneylis and Milaymis are the living expressions of this.

Thanks to their Parisian Olympic feats, added to the feat of five-time Greco-Roman champion Mijaín López (130 kg) and his classic teammates Luis Alberto Orta (67) and Gabriel Rosillo (97), wrestling, unquestionably, became the best Cuban sport in 2024.

To put into perspective the performance of Yusneylis and Milaymis, it should be noted that only the 16 best wrestlers in each of the six weight categories were able to register for the competition in the French capital. Milaymis earned her ticket to clean tackle, backed by her fifth place in the World Cup in Belgrade (September 2023), while “La Chiqui” earned her passport through her great performance in the continental qualifier for the Americas that took place in Acapulco, Mexico.

There are distinctive elements that led them to achieve such performances and that, as a fundamental detail, can define their projection for a four-year period that will have its climax in Los Angeles 2028.

“La Chiqui,” as everyone knows Guzmán, went through the once solid pyramid of Cuban high performance. Her starting point is located in the special area of Santa María del Rosario, in the Havana municipality of Cotorro, where she began her adventure in the discipline of tackles and imbalances at the age of 12.

Her determination against any rival, her explosiveness in the entrances, and the control of her opponents in the standing position are among her main resources; in addition to the fact that tactically, at 28 and with the accurate guidance of Filiberto Delgado, she has grown a lot. On the other hand, physically she is an athlete who has suffered few serious injuries in more than three decades of high performance.

Her arsenal still has room for improvement, since the defense of the legs (especially the forward one, when she is in the standing position), the ability to unbalance in four points, and the resistance to force in the epilogue of the fights are elements to strengthen.

Her best tournament so far, beyond Paris, was in the Santiago de Chile Pan American Games: two technical superiorities, one strike, and only two points received in the final as part of five acts of battle.

“La Chiqui,” little by little, has been sneaking into the elite of a tough division, as the lower weight categories generally are. This is confirmed by her current sixth position (35,000 points) in the world ranking of her category, led by the 25-year-old Chinese Ziqi Feng, bronze in Paris, silver in Asia, and ace in the World Series stop held in Poland during the Polyák Imre & Varga János Memorial.

If the natural course of the current Olympic cycle continues, Guzmán would arrive at the Los Angeles mats at 32 years old, an age that, although advanced, is not an obstacle to maintaining her physical and technical-tactical abilities at high levels. It is enough to note that the U.S. and current queen under the five rings, Sara Ann Hildebrandt, was crowned a little more than a month before turning 31.

Meanwhile, Milaymis for me is the “Tallapiedra cyclone,” a special area where precisely the Havana native of just 23 years of age blew up a mat for the first time. And I say blew up because Marín has been a kind of kryptonite since her beginnings.

While at the EIDE sports school, she went the distance in all her fights, and when she reached the national pre-selection at just 15 years old, she began a “get out of the way so I can get in” with the established Mabelquis Capote, which ultimately saw her emerge as the top figure in the 72- and then 76-kg categories.

She is a whirlwind on the mat. She tackles, flips, throws with a two-arm hold and is fearsome with her Oguchi. Perhaps that same furious explosiveness has taken its toll on her at times, although to be honest, almost no other female wrestler at her age, except for the Japanese and Parisian champion Yuka Kagami, has Milaymis’ record.

In 2018, she brilliantly (32 points in favor and only one against in four acts) won the Youth Olympic Games in Buenos Aires, Argentina. She was just 16 years old. As if that were not enough, in the 2019 season she won twice and without a doubt both the Junior World Championships in Estonia and the U-23 Championships in Hungary. Out of nine fights, she won four by striking.

What is there to improve? Gain a bit in tactical fidelity, time control, and, consequently, in the management of the fights; improve her defense on the mat and continue incorporating resources and competitive experience of supreme rigor.

Unquestionably, the current sixth (32,100 points) of the world ranking in the fiefdom of the Kyrgyz Aiperi Medet (46,000) will be the undisputed standard-bearer of Cuban women’s wrestling in Los Angeles, although being exhaustive, none of her main adversaries at present ― except for the 33-year-old Turkish Yasemin Adar ― is over 27 years old.

Revisiting the genesis

To be clear about the real firepower of Cuban women’s wrestling and the disadvantage with which they have gone into the ring of insertion into the world’s elite, it is enough to point out that in the distant 1987, in the Norwegian city of Lorenskog, the first world edition of this discipline took place. However, it would not be until Athens 2004 that women would burst into the lofty panorama of the Olympics.

Since then, Japan has been one of the main powers in this specialty, with names such as the legendary Kaori Icho and Saori Yoshida, four-time and three-time monarchs in these instances, respectively. In fact, in Paris they won four of the six titles in dispute in this modality, leaving the remaining two in the hands of the United States.

Back to the Cuban scene, after the aforementioned breaking of the ice in 2006, it would not be until 2010 that the practice of women’s wrestling was extended to all the EIDE schools. So, with the push of Rodolfo “Popi” Alfonso, Elio Garraway, and several other trainers, the power that would take between three and four cycles to bear significant fruit was germinating.

In this sense, it is worth overlooking the bronze of Lienna de la Caridad Montero (55 kg) at the 2018 universal event in Budapest, Hungary. She was the first to reach the podium in an absolute World Championship of the specialty.

With sacrifices, Cuban women’s wrestling has made its way into the elite, despite years of disadvantage, little participation in higher-level competitions, and other aggravating factors of an economic and infrastructure nature. With all that on their backs, our gladiators continue to carry the backpack of dreams and successes, and today, without any hesitation, we can say that they have the well-earned label of best individual women’s sport in a country with such a threadbare sports movement.