Although the Neptune Fountain holds the record for most moves (six), according to Emilio Roig de Leuchsenring, Historian of the City, there is another “restless” one that apparently follows in the statistics: the Fuente de la India, also known as the Fountain of Noble Havana or of Havana.

The idea to erect the statue was conceived in 1835 by statesman and economist Claudio Martínez de Pinillos, Count of Villanueva, who held, among other positions, that of director of the General Treasury.

The project was part of a general plan that enabled economic advancement, the construction of hospitals and public buildings, bridges, roads, and the Ferdinand VII Aqueduct.

To improve Havana’s public ornamentation, the Count of Villanueva conceived the idea of placing monumental fountains along the promenades. According to an article published by S. de Urbino in the magazine Arquitectura in December 1936, a public subscription was held to raise the necessary funds. However, a biographical sketch of the Count housed in the City Historian’s Office also states that he financed this project from his own pocket and donated it to the city.

“The monument to Ferdinand VII had already been inaugurated that same year in the Plaza de Armas, and due to its success, the Colonel of Engineers, Don Miguel Pastor, was commissioned to design the plans for two new fountains; one would be called Havana, with an indigenous woman, and the other, the Fountain of the Lions,” says S. de Urbino.

The plans were sent to Genoa, Italy, where friends of the Count of Villanueva arranged a contract with the Italian sculptor Giuseppe Gaggini, who, assisted by the architect Tagliafichi, executed the project. The two fountains cost 40,000 francs, according to Roig.

Muse of chroniclers and poets

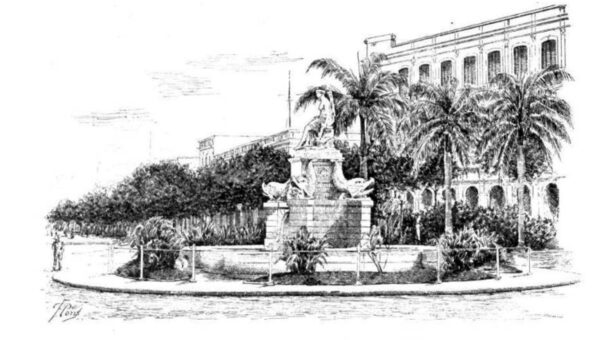

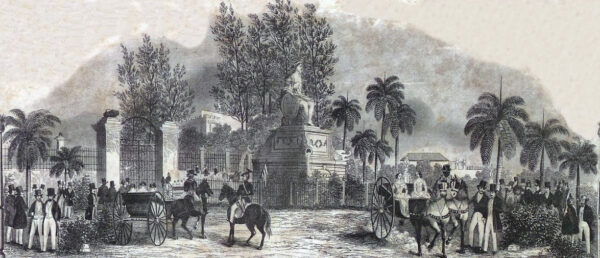

Carved from Carrara marble in the neoclassical style, the Fuente de la India was placed in January 1837 in front of the East or Tacón Gate of the Military Camp, in the place previously occupied by the statue of King Charles III, moved to the beginning of the Camino del Príncipe.

At that time, carriage rides around the avenue where the fountain stood were common. Furthermore, after performances at the Tacón Theater, the audience would linger for a while, chatting while the cries of merchants could be heard from street stalls, offering milk punch, hazelnuts, and various homemade sweets.

Due to its majesty, the sculpture aroused the admiration of both Cubans and foreign travelers, and inspired poets and chroniclers. Tranquilino Sandalio de Noda Martínez, a learned Cuban naturalist, geographer, surveyor, agronomist, journalist, and essayist, wrote an article in 1841 that read:

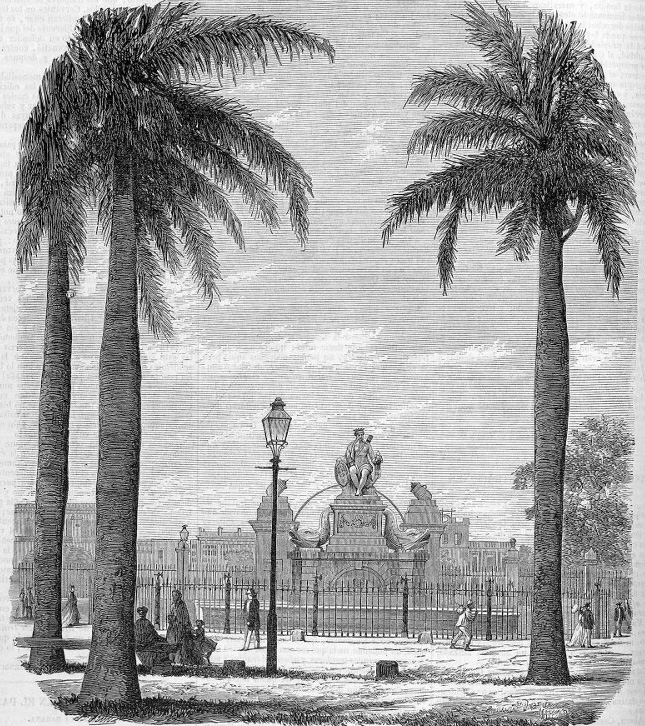

In front of the gates of the city of Havana…there is a white marble fountain rising on a rectangular pedestal, on whose four corners and prominent pilasters rest four marble dolphins, whose bronze tongues serve as spouts for the water that pours into the wide shell surrounding the pedestal…. Above everything, on an artificial rock, sits a beautiful statue representing a graceful young indigenous woman looking toward the East; her head is crowned by a feathered turban…and she carries a quiver full of arrows on her left shoulder.

The following year, Gabriel de la Concepción Valdés, Plácido, dedicated to it the poem “A la fuente de la India Habana.”

Look at Havana there, the color of snow,

a gentle indigenous woman of fine structure,

dominating a crystalline fountain,

seated on a small alabaster throne;

She never murmurs about her treacherous fate,

nor does she lament the sun that fascinates her,

nor does the harsh weather exterminate her,

nor does the furious tempest move her.

Oh beauty! Your suffering is greater

than that tenacious and expansive wall

that surrounds your beautiful pavement;

Yet you are all pure marble

without soul, without color, without feeling

made by blows with hard iron.

And in September 1850, Pablo Ortiga Rey, a Spanish literary vernacular person and public official, wrote a text entitled “Cuadro comparativo entre La Habana de 1834 con la de 1850,” published in two parts by the newspaper La Ilustración, in which he noted:

The Fuente de la India in Havana can only be compared to that of Madrid’s Cibeles. A colossal statue of beautiful stone, leaning very gently on a kind of carriage, and with the horn of plenty at its side, represents the perfect type of the indigenous race, whose forms and contours are described with admirable clarity and truth. Several genies and allegorical objects crawl at the foot of the image. From the sumptuous pedestal on which it is placed, four thick pipes emerge, depositing the crystal-clear liquid that passes through them into a limpid basin. A beautiful slatted fence surrounds the fountain, and a lovely little garden perfumes the space through the fence and the basin.

According to Emilio Roig de Leuchsenring, in a chronicle published in the magazine Social in October 1934, “of all the statuary monuments from the colonial era that Havana possesses, the one that deserves the greatest and most singular attention, for its artistic beauty and for its symbolism and historical representation, is the Fuente de la India….”

Moves

It didn’t remain in its original location for long. In 1841, it was placed in the second section of Prado Avenue, between the Tacón Theater, later the National Theater, and the gates of the wall, known as Montserrat. It remained there until January 23, 1863, when the City Council decided to move it to the center of what is now Parque Central, between San Rafael Street and Neptuno Square.

Havana residents believed that, at last, the authorities would leave the colossal indigenous woman alone. They were wrong. When the Bourbons regained power in 1875, the Havana City Council wanted to celebrate in style and decided to build a monument to honor Queen Isabella II, a sculpture to be placed in the Parque Central. So they moved the Fuente de la India again, this time to its former location on Prado Avenue. Although in a different position, it would face the Campo de Marte field for military exercises.

A few decades passed. General Gerardo Machado ruled Cuba. Under the direction of his Secretary of Public Works, the lawyer and businessman Carlos Miguel de Céspedes, in 1928 the Campo de Marte was transformed into the Parque de la Fraternidad Americana. But this time they didn’t move the fountain to a different location; they settled for changing its orientation: it would now face the sea. Furthermore, they placed it on a 3-meter base.

As the years went by, other symbols of the Cuban capital’s identity were incorporated. Perhaps the Fuente de la India no longer carries the same symbolic weight it once did, when it was said that anyone who visited Havana and didn’t see it would be as if they had never been in the city. Its reign was astonishing, as chronicler S. de Urbino expressed in his old 1936 print:

Today it is a symbol linked to the name of the City; we have no work of art that is as popular in Cuba as it is abroad, nor that has been reproduced so widely in lithographs, magazines, postcards, etc. It has become, as its creators intended, the emblem of the Capital, and it is inconceivable that the Capital is not represented by that noble statue, which, on the rock with her mantle over her shoulder and quiver on her back, seems intent on competing with Cupid.

________________________________________

Sources:

Arquitectura

Bohemia

El Museo Universal

Carteles

La Ilustración

Social

Semanario pintoresco español

Archive of the Office of the City of Havana Historian