– What do you think?, asked the hostess to Spanish essayist Don Federico de Onis, while he showed a legitimate lace bedspread, bought for the guest room.

The first thing she will do upon arrival is to lie on it with her muddy shoes.

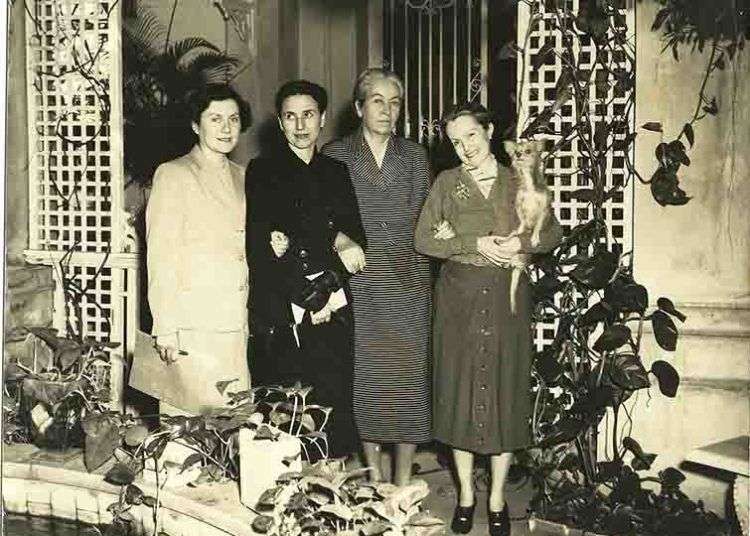

The hostess laughs, always jealous of the details, not knowing that prophecy would be fulfilled, although otherwise. Dulce Maria Loynaz receives in her home in 19 and E, in the heart of Havana, Gabriela Mistral.

Time has passed, it is true; more visit becomes increasingly mythical, more memorable.

The Chilean reached Havana in 1953 for the celebrations for the centenary of the birth of José Martí. She had accepted the invitation to stay at the mansion of Vedado, since she and Dulce had met before, off the coast of Italy.

She was not yet accompanied by the aura of the Cervantes Prize she received in 1992, already an old woman, but Loynaz was no stranger. She had published Canto a la mujer estéril, Carta de Amor a Tuk-Ank-Amen and the lyrical novel Garden; but then it was a privilege to receive the only Nobel Prize for Literature in Latin America.

Thus, she arranged everything. And the photos of both at the fountain were left to posterity.

“That corner was chosen by all, it always respected, and I would not meet her, unless she called me. Then we sat together and talked, or rather, she talked (…) because my friend was more talkative than me, and also had more to say. ”

Once the hostess confessed that verse had elusive wings, and the visitors had a ready answer immediately: “Well, go up to look for it, my little one”.

However, they were not easy days. Dulce Maria described her as a snowy Chimborazo, that “like all geniuses, had her impertinence.” She refused to touch the money and when she was buying her secretary or hostess should take care. But that did not bring major disagreements, but some invitation…

The disagreement

Diplomatic authorities and prominent writers, demanded Dulce María by various means, to share such an illustrious personality. And, as occasion demanded, a strict etiquette lunch was prepared.

Just that morning, Gabriela Mistral rose “with a great need to see the sea”, and since no oen could impose her standards, she left. In vain were messages, phone calls. She appeared only when all were gone.

Tested her pride, the Cuban lost her temper at the Nobel herself: “(…) when Gabriela arrived that night, she found a note in her room where I told her that since she did not seem to feel comfortable my house (…)I preferred to sacrifice mine to have her there. And the next day, she moved to a hotel. ”

The reconciliation

In any case, poetry with its subtle thread ended bridging. At the Lyceum Law Tennis Club Havana, Dulce María gave in 1957-year of the death of the Chilean-the Lucila y Gabriela conference. It would then be chosen as a prologue to the Complete Poetry of Gabriela Mistral, published in Spain in the Nobel Prize collection.

“Now Gabriela (…) I need to tell you something. To be a Queen then you came, as in the games of your childhood: golden pheasants and milk trees contemplate you now, taller than the hundred mountains of your valley. “