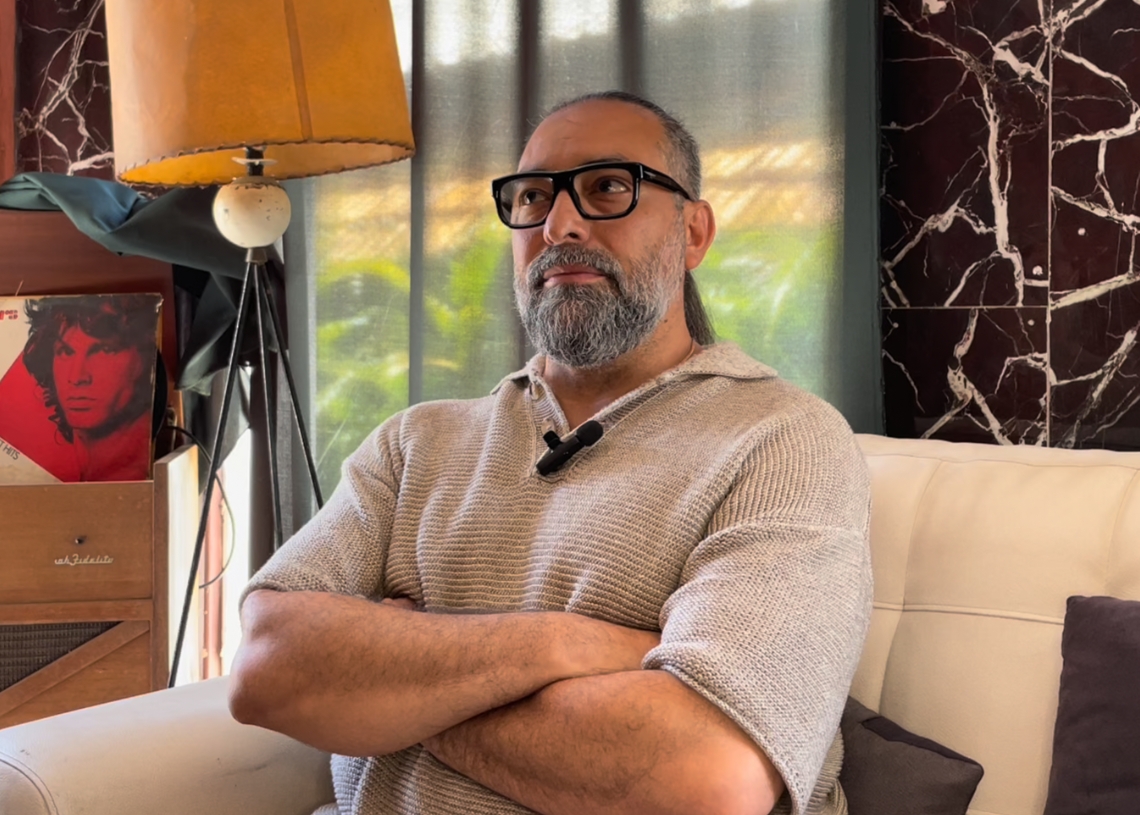

Alain Pérez is one of the most powerful energies in Cuban popular dance music today. For a decade, he has been developing his solo career leading his orchestra and although that marked his breakthrough for most of the Cuban public, his career was already long and well-established.

Ever since he was a student, many noticed the birth of a star. Irakere, Isaac Delgado’s orchestra and the group of the great Spanish guitarist Paco de Lucía are among the most distinguished he has been part of on a journey that began on the island and then continued in Spain.

Musical production has been another field in which he has reaped many rewards: from Celia Cruz, Omara Portuondo, Isaac Delgado to Concha Buika have placed albums and songs in his hands, before and after embarking on a solo career that brought him back home.

From here, he has conquered his island and much of the world, won a Grammy and become an essential name in Cuban music today, admired by his peers, an example for new generations and loved by the public.

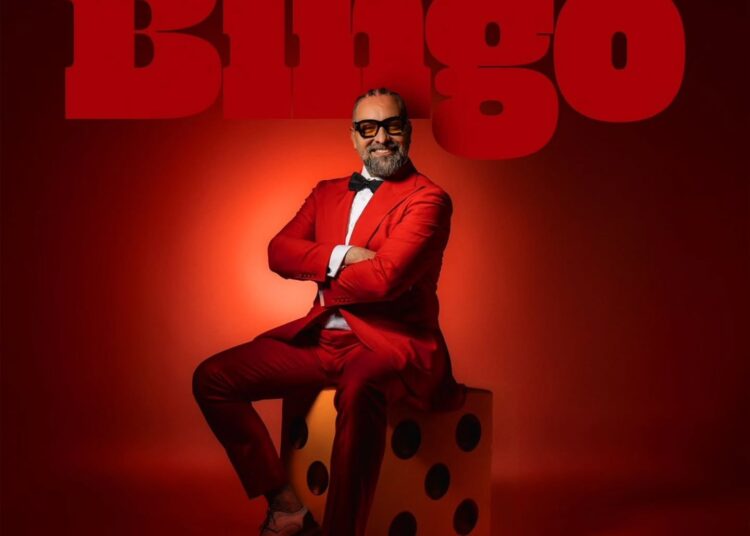

After five years away from doing so, he released a new album on May 30th.

“Bingo is a song of joy, of hope, of Cuban music. I was filled with ideas, of hope, of continuing to be on stage, of continuing to look play for my audience, my people, with my orchestra, with my musicians, with everyone who always embraces my music. That’s Bingo. The bell of music inside me rings again for you,” is how Alain defines this new production, which, while it’s been playing on platforms for more than three months, the artist has also decided to present live in a very special way.

“We’re going to present the album live on September 27 at the Karl Marx Theater. For the first time, I’m going to perform at the Karl Marx solo. I’m expectant and excited because the market and job opportunities in Havana are much scarcer and limited these days, but going to the theater means going to play for the people, and that’s what I want: to play for my people,” he tells us.

The concert will also feature his usual hits, but the artist assures us that those who attend “are going to hear a work whose idea was born 100% on the island, with the full excitement of making it here for you.”

Bingo was recorded between Spain, Miami and Cuba and is possibly the Alain Pérez album that, to date, brings together the largest number of collaborations with important names in international salsa: Gilberto Santa Rosa, Tito Nieves, Luis Enrique and Issac Delgado. This is where we begin a conversation about many paths.

Why so many big names for this album specifically?

Some people ask me, “Why did you waste all your bullets?” But they gave me the cue, and this was the moment. I hadn’t recorded in five years; a long time has passed since El Cuento de la buena pipa. The pandemic was one of the reasons that kept us from being able to record, work and maintain the rhythm and work dynamic we had. So I took advantage of it.

With Gilberto, for example, it was already a given and a desire for both of us to do something together, especially when he repeatedly told me we had to sing and I got excited and said, “Gilberto’s asking me for a song,” imagine that.

Luis Enrique is my brother; we have so many things in common; and Tito Nieves and I had met at two festivals, at Salsa al Parque in Bogotá, Colombia, and in Madrid, at Noches del Botánico. That night was the first time we played together, and he told me, “Hey, whenever you want we can do something.”

Isaac Delgado, of course, is always close, and I had already sung on his album. The song “Bingo” is really a tribute to the sound of Isaac’s orchestra, to our sound, the Palacio de la Salsa. It’s a direct nod to that 1990s timba and who better than Isaac to champion that song?

Everything happened that way, flowing through the energy of the brothers, of these artists who have collaborated with me, so no bullet is a blessing.

How did you choose the songs for this album?

I repeat a pattern of composers and authors who have appeared on previous works, as is the case, of course, with my father. On this album, my brother Rainer Pérez also appears as a composer; I’m working again with Juan Antonio Gómez Gil and I’m also throwing myself into writing a few things.

We choose the songs based on their dynamics. I want a danceable album that starts off on a high note, that has a curve. On previous albums I always do, let’s say, romantic songs, which have a softer, less aggressive content and aesthetic, but then we also do timba, which is super danceable.

In this case, I didn’t do a bolero. On previous albums, I almost always have a bolero, but this time I have very romantic, very beautiful songs. I have “Mi jardinera,” which is a song I wanted to champion for its story, its transparency. It’s also close to guajira music, to son.

There’s also “Ya no vale,” which is super romantic, it’s salsa, but it’s basically a ballad that I had written with my father for Ana Belén many years ago. On that occasion, we gave her “Ya no vale” and “Pero no termino,” and she sang “Pero no termino,” and that song stuck.

I imagine the album as if it were a show, a concert, very high-flying, but there’s always a curve of reflection, of listening, because regardless of the fact that we’re within the cells and the dance rhythms, I like people to listen to the songs.

When the repertoire for an album is decided, and there are those songs that have been in the drawer for years, what defines that this is the moment for that song?

I think it’s the maturity of the artist. For example, those romantic stories, back then when I was a young artist, they might not have suited me as much, but with my gray hair now, it was the perfect time to be able to present a love story in that way, so beautiful, like “Ya no vale.”

There are many songs I wrote with my father 20, 25 years ago that are still there, that I haven’t recorded yet. Of course, at the time they weren’t songs for me; they were songs written by my father, a person hardened by life and with experience, which is why they tell those stories like that. They weren’t songs for me, as a much younger artist, and that’s why now, little by little, I’ll be taking those beautiful songs out of the vault.

Why are you a little shy when introducing yourself as an author?

Because I’ve always been somewhat respectful and I greatly appreciate the value of the poet, the lyrics, those narratives, creating stories, songs and working with my father has always been so profound, so endearing, that when it comes to writing I always think twice about it. But well, over the years, I’ve been launching myself into saying things that I also want to share, ideas about life, as naturally and honestly as possible.

What does it mean to you that it’s through your father’s hand that those songs that have led you to success come from?

My father is the driving force, the mentor of my career, the person who told me to get on stage, dance, sing. Of course, my mother has always been there, Yolanda Rodríguez, who is always there with her prayers and blessing, but my father has found fulfillment in me; my successes are his successes and vice versa.

I always tried to make his work, his songs, known because I know my father was born with that passion for art, for music. The thing is, he was born there in Manaca Iznaga and life took him in a different direction. But he was always that artist from the patio or the doorway of my house, that artist I saw myself in; he was a motivation.

We’re talking about how I started writing songs with my father when I started playing guitar when I was nine. When I knew three chords, the first thing we did was try to make a song together, because I played, I had the harmony and he wrote the lyrics, just like a movie.

It’s been a very beautiful, very emotional, very endearing and demanding process, because my father is extremely demanding, especially in these times when you have to adapt to the language, change a bit and find a balance.

But then my brother arrived, completing the trio. Now we’re a perfect trio. My brother brings my father’s talents, but he also has my talents, and he also has the most modern elements. For this album, my brother wrote “Reina de corazones” and we wrote together “La Moneda” and “Andaba solo.”

Precisely that closeness to young people has been a constant in your orchestra, which has always been made up of musicians who have just graduated or even students from art schools. Why such a strong intention?

I want to share my music and leave a legacy, to teach and for that to be reflected in the new talents of Cuban music. Cuba is inevitably full of talent and thank God it’s one of the things no one can take away from us.

There are already two generations of young musicians who have passed through the orchestra, and how many times have we left a concert and I told them, “Everyone, let’s come here to talk,” not to fight, but always starting from the human side, to educate, not to damage or separate. Let the advice reach out as well as all the things I humbly have, and say them from the heart to form, and it’s true that I nourish myself, that’s reciprocal, it’s a working dynamic that also motivates me. They refresh me too, I have to get on their level, because the kids are into something else, they have a different way, a different energy, so we find a balance when it comes to working and continuing to make music.

From that experience of working with the new generations of musicians who are developing, do you think Cuban popular music still has a long way to go despite what we’re seeing right now with urban music?

I think so. I don’t know how long it will last, but right now, a generation of Cuban musicians is coming along, again, very good ones.

There’s always been commercial music, more popular, less popular, and trendy. What’s true is that Cuban urban music, or what reggaeton is now, and all the evolution they’ve been experiencing, has also brought them closer to more danceable Cuban music.

They’ve been very intelligent and realized that if they just kept making reggaeton, they’d be left out. So they’ve added those elements of traditional Cuban music, such as rumba and clave, and mixed them with electronic sounds.

I applaud what they do. What I’ll never share with them is the distorted language they use toward society, toward new generations, toward children, or speaking badly of women — all that stuff. But as for swing, they have swing, and I like it, and so does everyone else. It’s modern and it’s the modern music of kids, it’s the modern music of the night.

For example, Cuba never had a national disco music; it was always foreign music, house, or disco, it was always music from abroad. Now, music in the discos is Cuban; it’s the reparto music of the night. You can’t take that away.

Do you feel the need to express important things in your songs, not only through music, but also through words?

Music definitely has the power to convey a message, to convey words, to move people through their feelings, their emotions. All of that is implicit in the message, in the lyrics. How many things can a beautiful song say? How many stories coincide with our lives? How many stories resonate with our surroundings, with our friends, with our family? How many songs can touch our hearts? Lyrics have a power beyond compare, which is why when it’s a negative message, it distorts so much and causes so much damage.

Young people are vulnerable; they are developing, learning and encountering life. If you tell them that anything goes here, without restraints, that there are no values, no love, no respect, we are destroying instead of educating, we are deforming that society. And that doesn’t mean the songs are a sermon.

You just completed a three-month tour in Europe and the United States. Did you feel that even though you were outside of Cuba, you were connected to the Cuban public?

It’s incredible. Over the years, I’ve been able to experience and verify, and now more than ever, the emigration of that young audience that was originally here at my concerts, and now I play in Madrid and the people of Cuba are there, all that beautiful youth are there. And you go to Miami and the same thing happens. And it’s a wonderful reunion, that loyal audience, that seeks out my feelings, my songs, my dedication, my love for them, my life that is poured into my music, and they are there, and one is always grateful because those people who go there are a loyal audience.

These long tours are a tremendous sacrifice because I do them only with my team. Here, there’s no multinational, no record label, no this, no that…. Here, it’s from the heart, and that’s why I’m grateful to the audiences who listen to my songs, who write to me, who follow me on social media, who send me their unconditional support. I’m truly grateful because what I do could have gone somewhere else, but no, it’s going in the right direction.

Do you think it’s necessary to create from Cuba to have an impact on those international markets?

At least I do, having already come from an experience outside of Cuba, of many years outside of Cuba. I chose precisely to return to my homeland to sow what we have, that little bit and that greatness, which becomes indispensable, essential, which is our music from Cuba, in spite of everything.

Each to their own reality; mine is to be inspired by what I wanted to be at a time in my life that was written in stone, which was from Cuba.

I have countless artist brothers and sisters who make music from all over the world, and I know that deep down, you always want to return and play for your people and feel here what life gave us. This land gave me life, my mom and dad, my town, my people. That makes the difference.

With the number of artists making Cuban music outside the island, with other styles and markets, do you think Cuban music is being built today on two parallel paths?

I think so, and that these two markets are compatible. There are artists who are focused, who feel the commitment, the conviction to continue making Cuban music wherever they are, wherever and however they can. I think they are two markets that are joined: Cuba’s market and the market for Cuban musicians outside of Cuba, and together our music, which is one, becomes stronger.

How does Alain see himself in five years?

I see myself on stage, singing, jumping, teaching, sharing my music, trying to be…trying to be, no, I am the man, the son, the father, the friend, the Cuban brother, at heart, always for and with all my people.