A Sunday in the summer of 1890, with no further record on the calendar. The man who lives amidst wars, both within his soul and the one he is preparing to achieve Cuba’s independence, seeks a moment of peace in the white pine house that Carmen Miyares runs as a summer boarding house in Bath Beach.

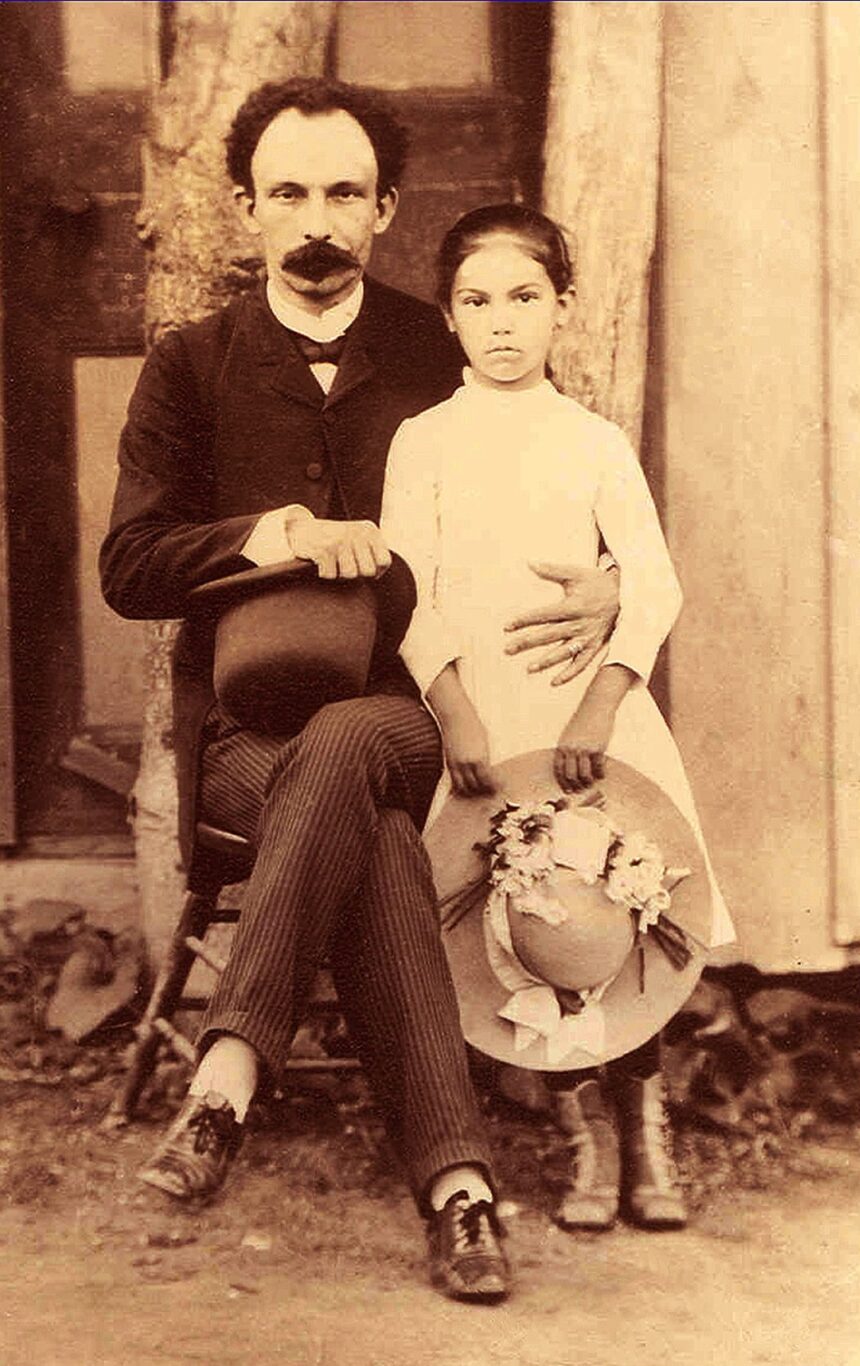

Wearing a high-necked dress, ankle boots, and a flowered hat, María urges him on. He takes the nine-year-old girl by the hand, and they go for a walk on the beach. His gestures toward the little girl are so tender, and their faces share such a similar appearance, that those who see them cannot think of anything other than a father and his daughter.

Near a tree, he suddenly calls out for her to stay still, as a bee is buzzing around her. Despite his caution, the vicious bee stings his little girl on the forehead. He trembles. Enraged, he crushes the insect between his fingers. In a shack along the road, a strikingly thin and plain woman offers them water to ease the pain.

The incident, immortalized with its dramatic intensity in Versos Sencillos (Simple Verses), still sends shivers down one’s spine. By a twist of fate, a traveling photographer crosses the scene with his camera and tripod. He smiles at them. They agree to pose before that dark and claustrophobic device that captures the moment for posterity.

In front of a recognizable back door typical of a U.S. house, the man dressed in black sits with his bowler hat draped over his crossed knee, his shoes polished, his gaze grave; so revealing of his spirit that one can read a glossary of solitude and silences like mountain abysses.

In a soothing gesture, he clasps the hand of the little girl dressed in white, standing against his left side, where the heart is — referring to the original photograph; let us look closely at the precision of the fingers, spread emphatically, clutching something they do not want to let go of; as only someone obsessed with protecting or shielding — more than consoling — a loved one from hostility, from an insect…from life.

Amidst the contrasting black and white that permeate the portrait in a whimsical symmetry, between the look of tenderness and fright that shines through in that region of the eyes and forehead — so subtly parallel in both — they remain together for eternity. I join those who have described this image as the most beautiful, moving and intriguing within Martí’s iconography.

The girl in white treasured that tape portrait until old age, a portrait that, like a true frame from an existential sequence, had a before and an after. Experts in photography say that every photograph contains an intimate confession. Was this one going to be any different? Almost five decades later, María Mantilla would open her own can of worms without hesitation: she claimed to be the daughter of that man dressed in black, José Martí; the most eponymous figure in Cuban history.

A letter that changed history

In February 1935, a letter arrived in the mailbox of Cuban-born actor César Romero in Hollywood. Sent from New Jersey by his mother, María Mantilla, the letter’s author made the matter clear from the opening lines: it was time to share a secret he needed to know.

By then, César Romero was a box-office draw, though his fame would skyrocket later when he portrayed the Joker in the ABC television series Batman in 1966, long before Joaquin Phoenix starred in his version.

Far from it, there was nothing joking about this confidential nine-page document. María recounted domestic events from the time the outlaw José Martí, after a long journey from Spain, arrived in New York on January 3, 1880. A winter of anguish. On the recommendation of a friend, he stayed at the modest boarding house of the Mantilla-Miyares family, where “the hearth fire and friendly words comfort the grieving guest,” as Mañach said in Martí, el Apóstol.

“He lived with us for seventeen years,” María recounted in her message to her son, falling into the trap of exaggerating the length of their time together, “until the day he left to fight in Cuba.” Martí not only found refuge and hot chocolate to ease the gray days of Brooklyn under that roof; there he also expanded his circle of friends with patriots and intellectuals, enjoyed the affection of the children, and his yearning soul quietly healed its wounds through the sensitivity of Carmen Miyares.

“He soon found in her a support, a counselor who offered him a friendship that would never end, and she was a great help in Martí’s life, a source of strength even in his redemptive work,” testified Blanche Zacharie de Baralt, author of El Martí que yo conocí.

Martí lived between two Carmens when, in March, he brought his own family to New York. Fed up with the life of emptiness, upheaval and deprivation alongside her husband, an eternal conspirator, Carmen Zayas Bazán returned to Cuba with young José Francisco in October 1880. A month later, María was born. It’s not difficult to deduce that Carmen Miyares’s pregnancy must have occurred between late February and early March.

Almost as an exculpatory insinuation — which I would call a condemnatory one — the idea was planted that by that time Manuel Mantilla Sorzano, María’s legal father until proven otherwise, was practically a frail, paralytic old man in a wheelchair, incapable of fulfilling his marital duties.

Based on the New York Census of that year and the death certificate, some historians have already refuted the claim that Mantilla was as diminished as he is portrayed. He was 42 years old when he died of a heart condition at noon on February 18, 1885. In any case, his death left Carmen a young widow.

I prefer to believe that María didn’t want to disrespect Manuel Mantilla’s memory in her letter to César Romero: “I want you to know, my dear, that Martí was my true father and I want you to be proud of it. Someday we will talk a lot about all this, which, of course, is only for you, not for publicity. It’s my secret and your father knows it,” she wrote clearly, in English, as if finally admitting that it had to be done in silence.

Would María, raised with respect for God, have so blatantly committed the sin of bearing false witness, knowing that it contradicted the norms of the time and called into question Martí’s ethics? Could that mind, to whom Martí — all passion, all brain — instilled the philosophy of “much shop, little soul,” have had any reason to concoct such an inconceivable lie?

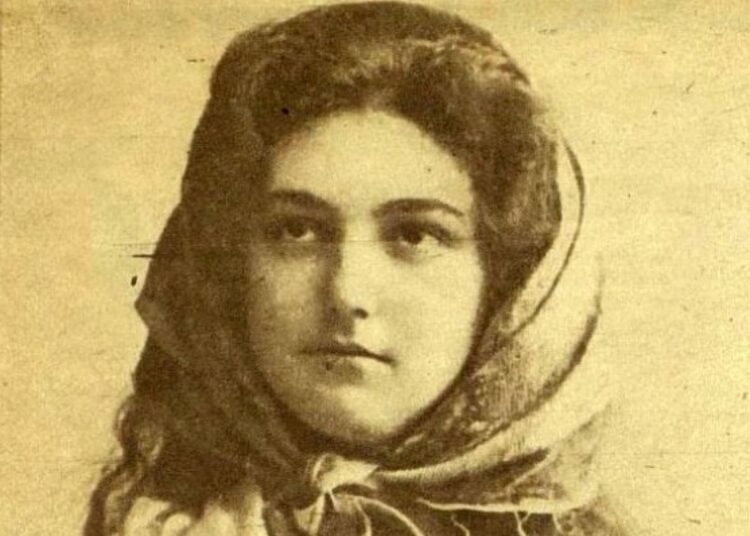

María, the saint?

A photocopy of a notarized birth certificate confirms that María was born at 4:40 a.m. on November 28, 1880. She was the fifth and last child of the marriage between Manuel Mantilla, a 37-year-old merchant from Santiago, and Carmen Miyares, eight years his junior and in charge of a boarding house.

The newborn was baptized on January 6, 1881, at St. Patrick’s Parish, located at 285 Willoughby Avenue, by Reverend Thomas A. Taaffe. “Joseph” Martí and Gertrudis Pujals, sister of the future General Vicente Pujals, served as godparents.

María lived most of her life in New York with her mother and her siblings Carmencita, Manuel and Ernesto. Martí, who channeled into her “the streams of tenderness he could not bestow upon his Ismaelillo,” largely instilled in her a love of study and reading, taught her French, and took her to concert halls.

Each time he embarked on a long journey, he would leave her with a notebook of assignments beforehand. Even with “life on one side of the table, death on the other, and his people at his back,” he wrote her letters brimming with poetic love and generous advice, educating her to know the truth of the world and to love with will and affection. He prepared her for a virtuous life and work, to be equal to or better than those who, as an adult, might try to court her.

Barely into adolescence, María Mantilla was attending political rallies and collaborating with revolutionary clubs. Around that time, she discovered another of her passions: the theater, especially opera and singing. At 21, she performed at the Tacón Theater in Havana. A contemporary edition of El Fígaro magazine wrote: “A daughter of the United States, she loves Cuba dearly. Beautiful, elegant and distinguished, her appearance at one of the last and most exclusive parties was a resounding success.”

Many years later, when questioned by Félix Lisazo, the former child recalled that distant Sunday when Martí took her for a walk on the beach, and how the iconic photograph came about. “The light that María Mantilla sheds upon us, as a reflection of Martí’s light, should have a profound and comforting significance for everyone,” the Bohemia magazine reporter maintained.

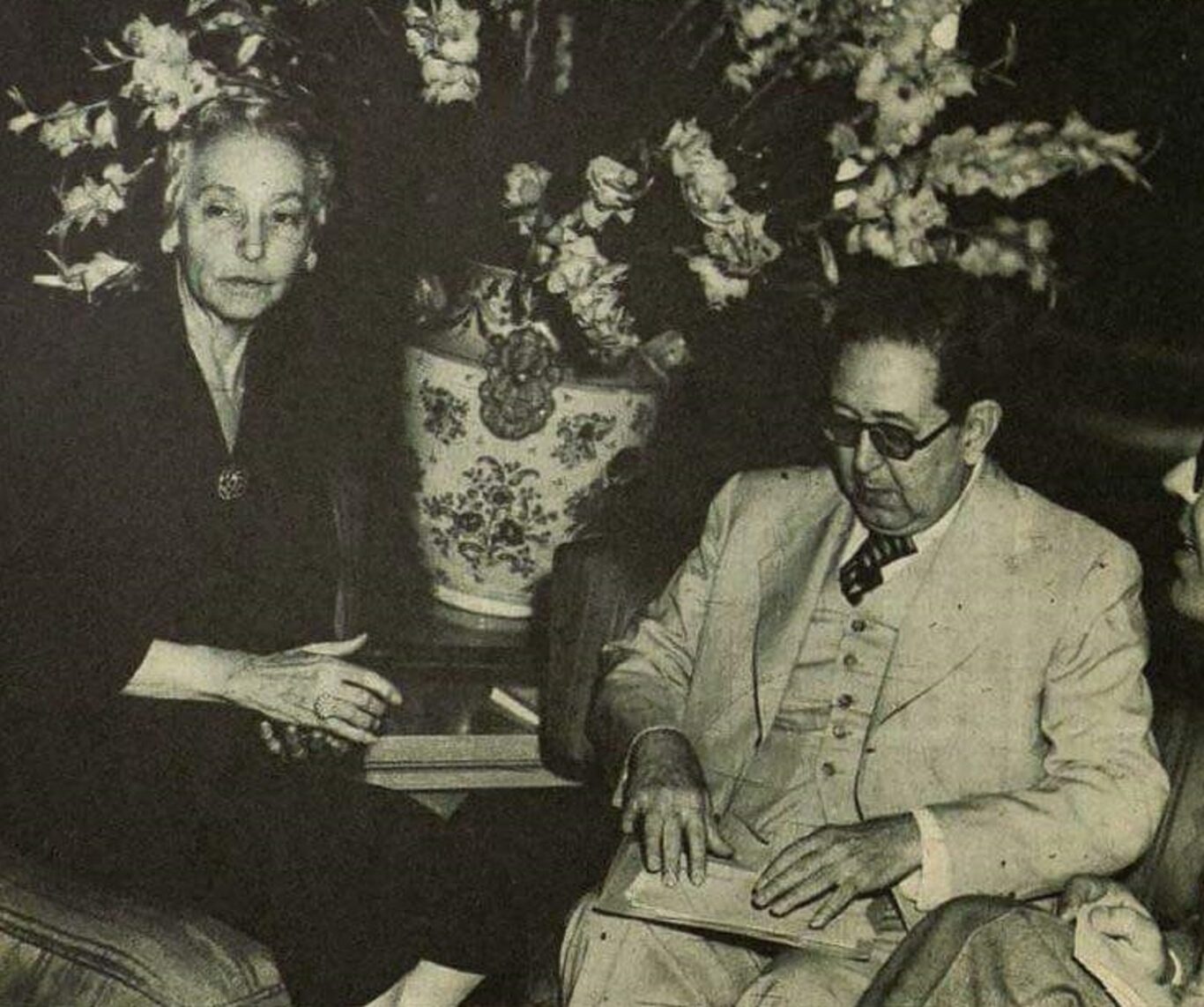

Recovering from a recent ankle fracture and with a strict prescription to control her diabetes, María landed in Havana on January 25, 1953, as a guest of honor — through Emeterio Santovenia — for the celebrations of Martí’s centennial. For the occasion, she donated important documents to the National Archives.

In 1908, she married César Romero, a commander in the Liberation Army, with whom she had four children — María Teresa, Graciela, César and Eduardo — and whom she widowed in 1950. Just shy of her 82nd birthday, she died in Los Angeles, California, on October 17, 1962. Some newspaper obituaries announcing her funeral referred to her as María Mantilla Martí de Romero, or simply, María Martí.

Controversy that persists

Surely, questions about heresy and accusations of mudslinging will resurface. However, it is not the intention of this text to stir up the praetorian guards surrounding the alleged parental relationship between Martí and María Mantilla.

I understand that despite having been addressed for a century by all sides, it remains a taboo subject in Cuba. Even so, the attempts to lock it away with a Pandora’s box haven’t been able to prevent the debate from rearing its head time and again.

But, while it’s not relevant now, nor is there space to recount the whole story, I assume the same right — or risk — as those who have preceded me, to share six points that I consider essential whenever this controversy is mentioned.

- The outpouring of emotion that María poured out in her letter to her son had a second chapter, twenty years later, in her correspondence with Gonzalo de Quesada y Miranda, son of Martí’s secretary and confidant. Unlike the secrecy previously demanded, this time her revelation was open. She couldn’t remain unmoved by a figure who was grabbing headlines by claiming to be the grandson of the Cuban National Hero. “As you know, I am Martí’s daughter, and my four children are his only grandchildren.… I assure you that this matter has caused me great sorrow, and realizing that I don’t have many years left to live, I want to reveal to the world this secret that I hold in my heart with such pride and satisfaction,” she declared bluntly on February 12, 1959.

- In a return letter, Gonzalo was no less critical: “We all know that you are [Martí’s daughter], and if, for example, we Quesadas have never expressed it publicly, it is because it is only now that you have authorized it…. I believe, then, that if you are resolved to reveal this secret — which in reality isn’t a secret, but which takes on special significance coming from you — the only thing I could do in this case is write an article….” The letters appear in the book La patriota del silencio: Carmen Miyares, by Nydia Sarabia.

- Carmen Miyares and María learned of the Dos Ríos tragedy from the New York Herald. Estrada Palma asked them to spend their mourning period in Central Valley, where acquaintances would come to offer them comfort. Among the letters Carmita wrote during those bitter days, the one sent to Irene Pintó stands out: “You can imagine the state of desolation I am in; this is the greatest sorrow that could have befallen my soul. I don’t know how I will be able to bear so much pain. I swear that if it weren’t for these children of mine, I would lower my head and let myself be carried away by this grief that is doing away with my life. Imagine what will become of my life without Martí, the greatest love of my life. All my happiness has gone with him: for me, the sun has been eclipsed, and I will live in eternal darkness.… Martí had become one with our souls….”

- During his lifetime, Martí was aware of the shadows of love affairs that loomed over them. Incidentally, in 1989, the Yearbook no. 12 of the Center for Martí Studies published an unpublished draft letter that — around 1885 — he addressed to Victoria Smith Miyares, living in Venezuela, who had harshly reproached her cousin Carmen for her alleged infidelity. “Now, as for the gossip, what can I tell you? Neither Carmita nor I have taken a single step that she wouldn’t have taken naturally, had I not been alive, or that, given the degree of moral responsibility, of piety, if you will, that her situation should inspire in every good man, a close friend of the family shouldn’t have taken — a friend who is no more so today than he was when Carmita’s husband was alive. I repeat, I know how to take care of this: if some wicked person, who, judging by the growing esteem in which she and I live, are surrounded, suspects, without any possible justification and against all appearances, that she receives a favor from me that tarnishes her, that, Victoria, will be one of many evils, much less [attributable] and widely spread than others, that mercilessly wound undoubtedly good people for years on end, who bear them calmly.”

- At one of the banquets organized by the Centennial Commission, María and Teté Bances, widow of General José Francisco Martí Zayas-Bazán, met. “I didn’t know María Mantilla personally. I only had hearsay about her. This subject was delicate with my husband, and we never spoke of María’s existence,” Martí’s daughter-in-law would confess. But at the banquet, she was astonished: “When I saw her for the first time in person, and quite close up, I was struck by her resemblance to Pepe Martí, my late husband. I couldn’t believe that this physical resemblance was related to Pepe. As I watched her converse with those around her, I noticed that her gestures, her smile, even the way she sat, aside from the physical resemblance — her face, her hands — were so similar to Pepe Martí’s that I couldn’t help but be convinced that there was a family connection between them.”

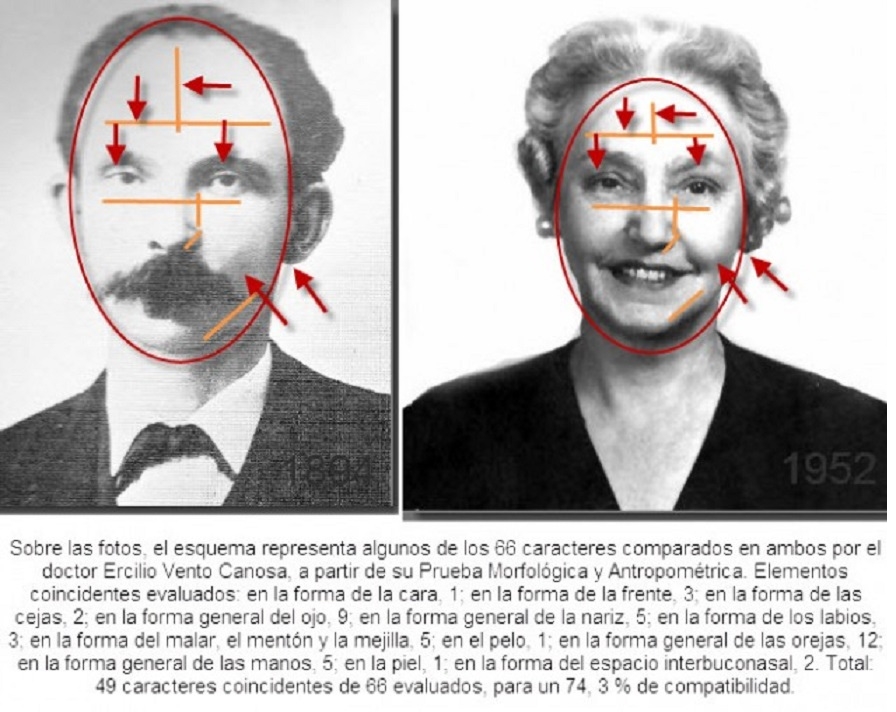

- Dr. Ercilio Vento Canosa, a man of history and science, also meticulously examined specific details to complete a comparative morphological and anthropometric examination in 2012, a patented technique for use in paternity suits before legal courts. Convinced that his attempt to seek scientific truth might “reap some unease,” the expert reviewed extensive photographic material of Martí and María Mantilla, verifying points of convergence in the axes of their eyes, eyebrows, facial shapes, nasal angles, corners of the mouth and several other features, concluding with an incredible 74.3% similarity index. This extraordinary analysis, along with other supporting evidence, was published by Yamil Díaz Gómez. “Let the DNA test be done. I never said this was the only conclusive proof; however, with this test, there are no elements to deny the alleged paternity,” Vento Canosa concluded.

Pocket photo

When, driven by his quixotic nature, Martí took the bow oar and felt the great joy of landing in the war, he carried with him a photograph of María Mantilla. As he wrote to her under the sun of Free Cuba: he marched with her portrait on his chest, like a bulletproof vest. Struck down — and not only by enemy bullets — José Martí fell, ambushed by a dagame tree.

In the forest of History dwells the whisper. The rustling of leaves — even those of incunabula — scatters whispered truths. In what universe does the wind not blow? Just because you don’t understand it, doesn’t mean you should reject it. It’s worth remembering that sometimes the questions are much more interesting than the answers. The dead man — who used to dress in black and whimsically rode his last horse as if dressed for a party — was found with a small, bloodstained photograph of a little girl in his left pocket.