Danza Contemporanea de Cuba (DCC) released an old quality, that of being reversible, with a new work by the Belgian-Colombian artist Annabelle Lopez Ochoa, who said “the soul has no gender.” This is the essence of the demanding, attractive, free and complex choreography while understandable in its speech and open to infinite interpretations.

The main modern company in the country transits from universality to the Cuban as naturally part of the intimate and delves into foreign formulas. Whoever wants to predict where one begins or ends, risks a lie or ridicule.

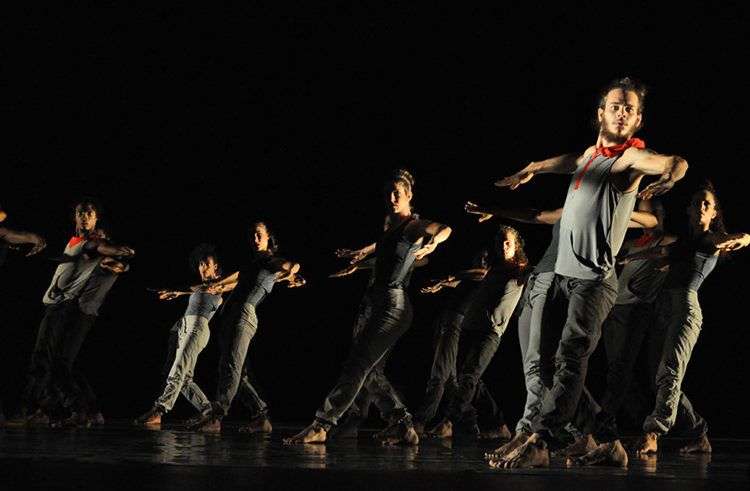

Limits? None, the Caribbean group each year works with multiple choreographers, styles, senses and let the dancers onstage see no differences in age or academic level, even in skills like partnering, or domain of either genre. All serve a ballet with manners of first dancers.

While the ballet accustoms us to specific technical steps for each sex and forces the man to always be the mainstay of the dancer, contemporary dance called for an executive democracy, so that not even the dangerous lifts have genre. In DCC all look good partners, and for the record, this is not a spontaneous or readily available quality.

If anything distinguishes this company is the balance, despite necessary new arrivals because the outings of some valuable members in recent years, the level remains high, evidenced by fierce critics as the London Guardian and The Telegraph. And although this is not the concept of Reversible supporting the work of the Belgian-Colombian choreographer López Ochoa, undoubtedly makes good use of the qualities of a group that defends each piece with lots of energy.

The world premiere happened last January 9, like Mercurio, the latest creation of the young Cuban choreographer Julio Cesar Iglesias, who in 2014 received praise by El Cristal. Creation that brought together technical and interpretive brilliance of the versatile company with a plural discourse capable of connecting times, fashions, ways, seduction of fame, snobbery and effectiveness of the culture industry, among many other points of view. El cristal surprised by the interest of great weight content and exhibited a jubilant company.

Maybe the creator had to wait a while longer to shape the next play, Mercurio, where six excellent dancers were not entirely comfortable, despite being a technically less demanding choreography than others. The title itself provides clues about possible alloys, insoluble, incompatibility, conductivities, ie relationships and struggle between opposites. However, it was not entirely clear on the scene and overran platitudes. Mercurio lacks intensity and its name is as graphic as betraying; it lacked preparation for filling it.

DCC seemed to enjoy Reversible, with its exploits of sensuality, exploration and interesting debate on the feminine and masculine, supported by a sober costume design by Vladimir Cuenca, adequate lighting by Fernando Alonso and evocative musical compositions as Valse sentimentale by Vladimir Sidorov and Kurja, by Titi Robin; among others.

According to the choreographer, all human beings have of both genders although in behavior one outweighs the other, either spontaneously or because of social pressures.

“The soul has no gender,” says Annabelle to emphasize the essence of the new work, applauded at the Mella Theater in Havana.

The program was completed with the piece Identity (-1), by the Cuban George Céspedes, winner of the Ibero-American Choreography Award 2002. Since its premiere in 2013, this has been one of the most common staging of DCC and really the artists displayed in it the feature pride of the company, despite the choreographic redundancies.

The Cuban company received the 2009 Award Moon in Mexico by Céspedes version of Carmina Burana, at the National Auditorium. A year later, the piece commissioned by Mambo 3XXI earned nominations for the three major awards in the UK for dance: the TMA (Theatre Award), the Laurence Olivier Award and the National Book Critics Circle Dance. Although during the preparation process of Identity the choreographer stated that with the piece he sought to distance from Mambo, the work was more a sequel, short of the excellence of the predecessor.

At 56 years of artistic life, DCC continues unprejudiced searches, undertake daring ways, not closing doors, tests, and defends each experiment with an enjoyable, contagious ferocity. That it has been successful, no one doubts it. Bravo!