Many Americans visiting Cuba say that they want to see the country now, before it opens up, assuming that recent changes in Cuban internal policy and Cuba-US relations will change in tune with exigencies of global capital, and that, as a result, Cuba will cease to exist as an anachronism in the world.

Some of them, as well as friends and family back home, consistently ask me if living in Cuba feels like the stories I heard growing up about life in the mid-1900s.

The concept of a “time-warped” Cuba has served to incite intrigue and evoke romance, but also to give way to misconstrued views that position Cuba as retrograde, isolated from outside influence, and disregard the efforts made by Cubans themselves to connect.

Although the abundance of old cars -American and Soviet- might lead visitors to think otherwise, Cubans have created seemingly infinite networks and mitigated intricate limitations, mostly in informal ways, to keep Cuba in link with the rest of the world.

The Internet

In Cuba, even in Havana, it can be difficult to go on the internet, and what is available is both slow and expensive. Although this past summer the Cuban government’s only network provider, Etecsa, began installing WiFi spots all around Cuba for a reduced price of the equivalent in Cuban convertible peso (CUC) of US$2.00 an hour.

These are usually located in public streets and parks, where now crowds of people sit or stand zoomed into their smart-phones and tablets, (video)chatting or checking their social networks, news sources and the like.

With the high demand for internet use, WiFi cards bought at Etecsa stores “go missing” – as Cubans would phrase it. Many unlicensed sellers stand on street corners re-selling these cards, illegally sold and bought in bulk from Etecsa, for an increased price of $3.00 CUC (nearly 4 dollars).

This likely both aids in the process of making WiFi cards more accessible, and adds to the demand that makes them go missing in the first place.

Despite the partial advances in internet availability and accessibility, and to some degree due to obstacles sprung from this same process, Cubans continue to find ways to best connect with family and friends outside of Cuba and to access latest information and entertainment. Some pay for a Nauta service, operated by Etecsa, for e-mail use on their cellphone.

Also, many Cubans living outside of Cuba afford communication between Cuba and the exterior. Some use applications like Cuballama to contact family and friends living in Cuba at reduced prices, dodging expensive fees that would otherwise limit calling or messaging directly.

The Weekly Package

Perhaps the star tool for entertainment and news consumption, which is neither state controlled nor largely sanctioned, is the paquete semanal. This is a weekly subscription to a terabyte of information, national and international, that includes everything from magazines, news reports, television series, movies, local advertisements, among other things, with the strict exception of pornography or other material that could be considered morally questionable by the state.

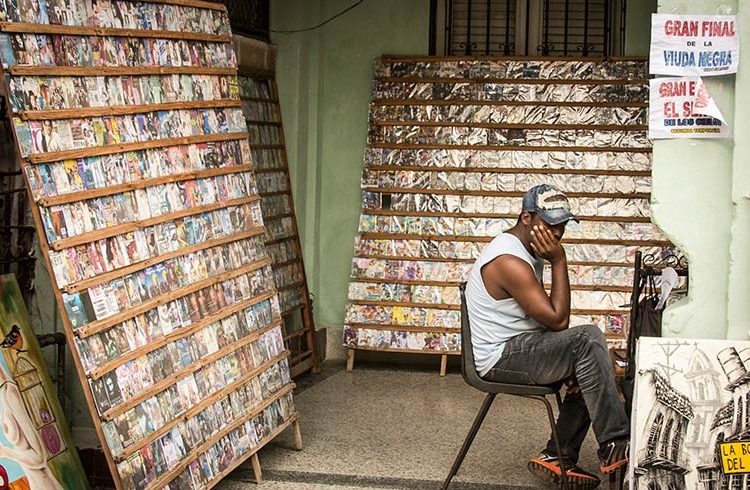

Most of its content is pirated, although the sources are widely unknown. Normally, sellers lend their buyers a hard-drive for a limited time for them to pick and choose what to copy onto a USB or computer. It costs $3.00 CUC at the beginning of the week, when information is most new, or $1.00 CUC at the end of the week.

Other methods

A precursor to the paquete, now less popular but still around, is the home video store, called banco de películas, for renting cassettes and, more recently, for renting but mainly buying DVDs and digital copies.

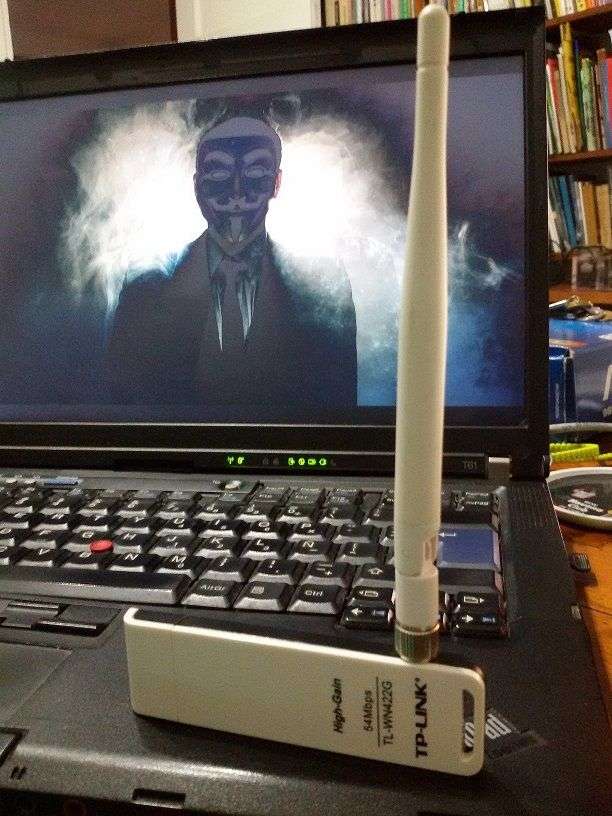

Some Cubans, users of a clandestine ethernet and WiFi network built exclusively for the sharing of entertainment and information, had antennas and ethernet cords installed in their homes.

Antennas are also used in tourist areas to pick up cable signal from hotels, which usually offer guests a selection of international channels that is otherwise unavailable in Cuba.

Internet paraphernalia mostly come through imports either by termed mulas or by friends and family living in the US, Latin America and beyond. Mulas work between Cuba and other countries, either to and from Miami, México City, Quito or others, selling a good amount of merchandise in Cuba, incidentally bringing with them trends in technology, fashion and the like. Mulas sell certain popular consumer goods unavailable in Cuba, and can also be contracted for specific items.

Similar to mulas, although not necessarily for business purposes, family, friends and visitors living in the exterior bring in important goods when they visit, either as personal gifts or to supply for business in Cuba.

Through these active efforts by Cubans to circumnavigate imposed restrictions on consumption and communication, and also resulting from immigration, tourism and business, Cuba is inevitably impacted by global trends and lifestyles, making it far from being an isolated island stuck in time.

*Juliana Unanue Banuchi is the Assistant Director for the Consortium of Advanced Studies Abroad’s (CASA’s) Cuba Divisional Center. CASA is a semester-long study abroad program comprised of 9 member universities, led by Brown University, and hosted in Cuba at Casa de las Américas and Universidad de La Habana. Originally from San Juan, Puerto Rico, she has been living in Havana, Cuba since September 2014.