Louisville, a city famous for horseracing and fried chicken, has become a hotspot for Cuban immigration.

Cubans are now the fastest growing immigrant population in Louisville and are poised to overtake Mexicans as the largest immigrant group, city officials say.

What’s remarkable is that most of the Cubans come from just two Cuban provinces: Holguín and Camagüey.

Many Cuban immigrants were from those two provinces early on. Word spread that Louisville was a sort of promised land for Cubans, and more travelers from Holguín and Camagüey set out for the city.

“There are so many people here from Holguín and Camagüey that I think those provinces are going to empty out,” jokes Dalay Méndez.

She heads the Cuba office at the Kentucky Refugee Ministries, which resettles immigrants in Louisville. Her office has been swamped with newcomers from Cuba.

She knows what they’re going through. She and her husband arrived from Camagüey in 2002.

Méndez says it was a difficult adjustment, “not knowing anyone, not knowing where to go, not speaking the language.”

But Méndez persevered.

“I feel at home now,” she says. “I like the city.”

The latest census figures show there were 9,190 Cubans in the Louisville/Jefferson County metropolitan area in 2014. Louisville’s share of Cubans was the second highest of any American city outside Florida, trailing only the Las Vegas metropolitan area.

Maylín Díaz, 25, arrived from Holguín nine months ago. She works as a waitress and cashier at El Sabor de Cuba, a restaurant on the outskirts of Louisville.

“People are very nice,” she says. “For those of us who are just starting out in this country, it’s a good place.”

But adjusting to a new country hasn’t been easy, she says.

“The first months are hard because you still don’t feel completely American, but you are no longer Cuban. You are just an immigrant,” she says.

“You are always waiting for a phone call or a message from your relatives in Cuba. You have a longing for the country where you were born, but you feel like it no longer belongs to you.”

City officials say they are grateful that Cubans are choosing Louisville.

“We value our new neighbors,” Mayor Greg Fischer says.

Cuban immigrants are seen “as a positive force for economic change and not a group who’s going to drain our resources,” adds Bryan Warren, director of the city’s Office of Globalization. “The only way economies grow is if people are entering into the community and the Cubans right now are a really big factor in that growth, a really positive factor in that growth.”

“Our population growth is currently dependent on strong immigration into our city,” Warren says, and Cubans “represent a bulk of our population growth. They provide workforce for jobs. They open businesses. They expand cultural diversity.”

Warren walked along Woodlawn Avenue, where Cuban shops sell everything from black beans to coffee and plantains.

“One of the great things about the Cuban population is they are extremely entrepreneurial and they take advantage of opportunities to start businesses in our city,” he says.

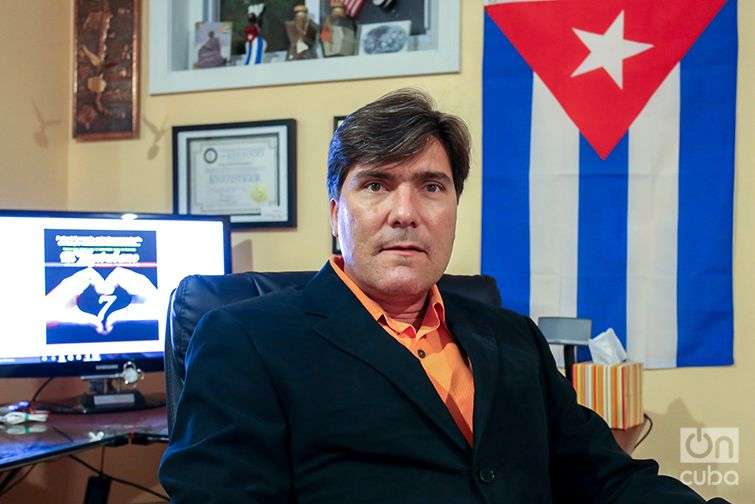

Sergio Estrada, 44, arrived in 2002 with his wife, two young daughters and about $100.

Today he runs a thriving real estate business.

“Your house with Sergio,” ads around town proclaim. “Call Sergio now.”

“Most of the people I know who are successful have a goal and they go for it and take it,” Estrada says.

He was an electrical engineer in Cuba. Once he reached Louisville, he realized he could do whatever he wanted.

“You have the world in front of you and all kinds of possibilities. You have so many roads to take. If you don’t lose track of your journey, you will be successful. If you fail, you just stand up and keep going.”

But no one expects success overnight. Coming to America is “almost like being born again,” says Carlos Aguilera, who settled in Louisville 12 years ago.

“Everything is different here,” the Holguín native says. “But in the end, the sacrifice is worth the reward.”

His first job was at a hog slaughterhouse.

“It was very hard,” he says. “In Cuba right now, almost no one works and once you get here you work a lot. Many hours on your feet. It’s very difficult.”

He left the slaughterhouse and drove a truck for four years before getting into the grocery business. Today he manages a Latino grocery store, Value Buy Market.

He is proud of Cuban roots and hangs the red, white and blue Cuban flag from the store’s front window. But he says he has worked hard to adapt to his new homeland.

“I got used to how they live here, the Americans, and I’ve tried to live as peacefully as possible so I don’t have problems with anyone.”

A truck from Miami pulls up to his store every week and unloads tropical fruit, vegetables and refreshments.

“Here in Kentucky, in any store, you’ll find one or two Cubans or even more,” he says. “Before you didn’t seem them, but now wherever you go you’ll find Cubans.”

Newcomers include Rubén Reyes, 27. He arrived in May from Holguín, where he was a tour guide. He likes Louisville, but misses his 1-year-old daughter, who he left behind with his ex-wife, and his grandmother.

“Sometimes I start thinking, laying in bed thinking about my life and say – I was happy in Cuba. I had a job I liked.”

He wonders whether he should have left, but decides he’ll stick it out in the U.S.

“This is a country that offers many opportunities for us and if you work hard I think we can achieve what we came here for,” he says. “Maybe not the American dream, being a millionaire and everything, but being happy.”

Paige Farris teaches a citizenship class for Kentucky Refugee Ministries in Louisville. Most of her students are Cubans.

“A lot of people miss home and so sometimes they think ‘It would be better if I went back to Cuba because I don’t have everything that I had back home.’ Everybody goes through that phase at some point,” she says.

Many have been through difficult times.

“The Cubans that I’ve talked to have had a hard time getting to the United States in many cases,” Farris says. “I know people who would maybe live in Venezuela for a little while and then they’ll walk through Central America to get to the United States. Other people come by boat to Florida, so it’s not a very easy journey.”

After all they’ve endured, most Cubans are “very grateful for what they have here,” she says.

“Most of the Cubans that I have worked with want to become citizens as soon as they become eligible because they want to give back to this country. They want to participate and vote. They want to be able to bring family members here a little easier, so there is a high drive, I think, to become U.S. citizens.”

Like many of his countrymen, Juan Carlos Labaut misses Cuba, but doesn’t regret moving to Louisville, located along the Ohio River just south of Indiana.

“We were in Cuba for many years trying to live with as little as possible. We sacrificed hours and hours working for very little money,” says Labaut, a truck driver. “Then we come here and work many more hours for a better salary. That motivates us to work more to be able to earn more and improve the economic situation of our family, not just here but in Cuba, too.”

Caridad Valentín Márquez arrived in May. She says she has “tremendous optimism” about her prospects.

“I don’t know much about this country, but I’ve heard that there aren’t as many jobs in other cities as there are here,” she says.

In Cuba, she worked in human resources. Here, she says, “I’m open to any job offer. I think that only good things are in store for me.”

Luis Miranda, 26, is also upbeat. He works at a shop that sells clothes, shoes and sunglasses while finishing his bachelor’s degree at Sullivan University in Louisville.

After graduation, he plans to pursue advanced degrees in information technology. “My ultimate goal is to work for the government, something IT-related, cybersecurity, networking, something like that,” he says. “Cubans here in Louisville…they’re here to stay and they’re here to grow for the best.”