The Cuban entrepreneurial world has experienced a significant diversification in recent years. For some that diversification is the logical way for the Cuban economy to adapt to the new conditions in which it has to live and develop; in the extreme and very extreme are those who think that that diversification is a symptom of Cuban socialism’s weakness which they have already imagined, frequently, a copy of that which we tried to build from the time of the socialist camp and the Soviet Union.

In that wide-ranging framework of discussions and diverse opinions, there are also those who attribute a part of the evils afflicting our socialist state enterprises to the emergence and expansion of a non-state sector (cooperative, national and foreign private) brought about by our government as necessary elements of the indispensable transformation. And before this sector emerged and expanded, what was the cause of the inefficiency of our socialist state enterprises?

There are also those others who understand that there is no sense to continue endeavoring to maintain a socialist state enterprise sector. And then how are we able to build a socialist society?

And of course, there are those who – and now I include myself – defend the idea of a diverse entrepreneurial fabric in the forms of ownership and management, led by the socialist state enterprise, consolidated in the really strategic sectors, that is, which decisively contribute to the strategic cores. An entrepreneurial sector, adequately regulated, functional for the aims of building the prosperous and sustainable socialism that is wished to achieve in this country that must continue being sovereign and independent and which must build a democracy that satisfies those aims.

All that diversity of opinions is also the product of political and ideological concerns, undoubtedly legitimate, since in these last 500 years in which the Homo sapiens have become almost a god, the enterprise has been constituted not only into a fundamental / essential “cell” of the economy of a country but also of its social and political dynamics. It is also thus for our Cuban socialism.

But the diversity of opinions, far from being damaging, is the principal source of good solutions. So welcome to the discrepancy.

However, I believe that understanding the currency of the Cuban enterprise obliges us to get to know the history of its evolution. I will take the risk of making a synthetic description of that long and complex process, where we unfortunately do not have (at least I don’t know of it) a “taxonomy of the evolution of the Cuban enterprises since 1959.”

I advance that it is impossible to isolate the evolution of that entrepreneurial world from the political and social determining factors of the revolutionary process – including of course the blockade of the government of the United States of America and our strategic relationship with the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Both, relations of dependency, although essentially different, that determined to a great extent the entrepreneurial structure, the form of organization and the regulatory system of our enterprises.

History does matter. The entrepreneurial world that the Cuban Revolution finds in 1959 was the result of the evolution of an economy that beyond half of the 19th century based its dynamics and wealth in the exploitation of slave work and in a leading product in the world market: sugar.

Later, from the start of the 20th century, that entrepreneurial framework would change drastically in its structure and in its ways of organizing. “The high dependence of our foreign trade, the phenomenon of large estates, the extreme specialization of production, the progression of foreign capital” [1], the mass immigration of Spaniards who occupied an outstanding place in the country’s economic dynamics and the dominating presence of U.S. companies in decisive sectors of the national economy, were pivotal in that modern configuration of the Cuban enterprise in those first decades.

Thus, the Cuban entrepreneurial world of the first half of the 20th century developed in an underdeveloped country, tremendously unequal and dependent, but at the same time and contradictorily, with a significant propensity for technological modernity and the world market. That entrepreneurial world [2] in itself was the reflection of that tremendous contradiction that emanated from the coexistence of modernity and underdevelopment, so graphic in the Cuba from before 1959.

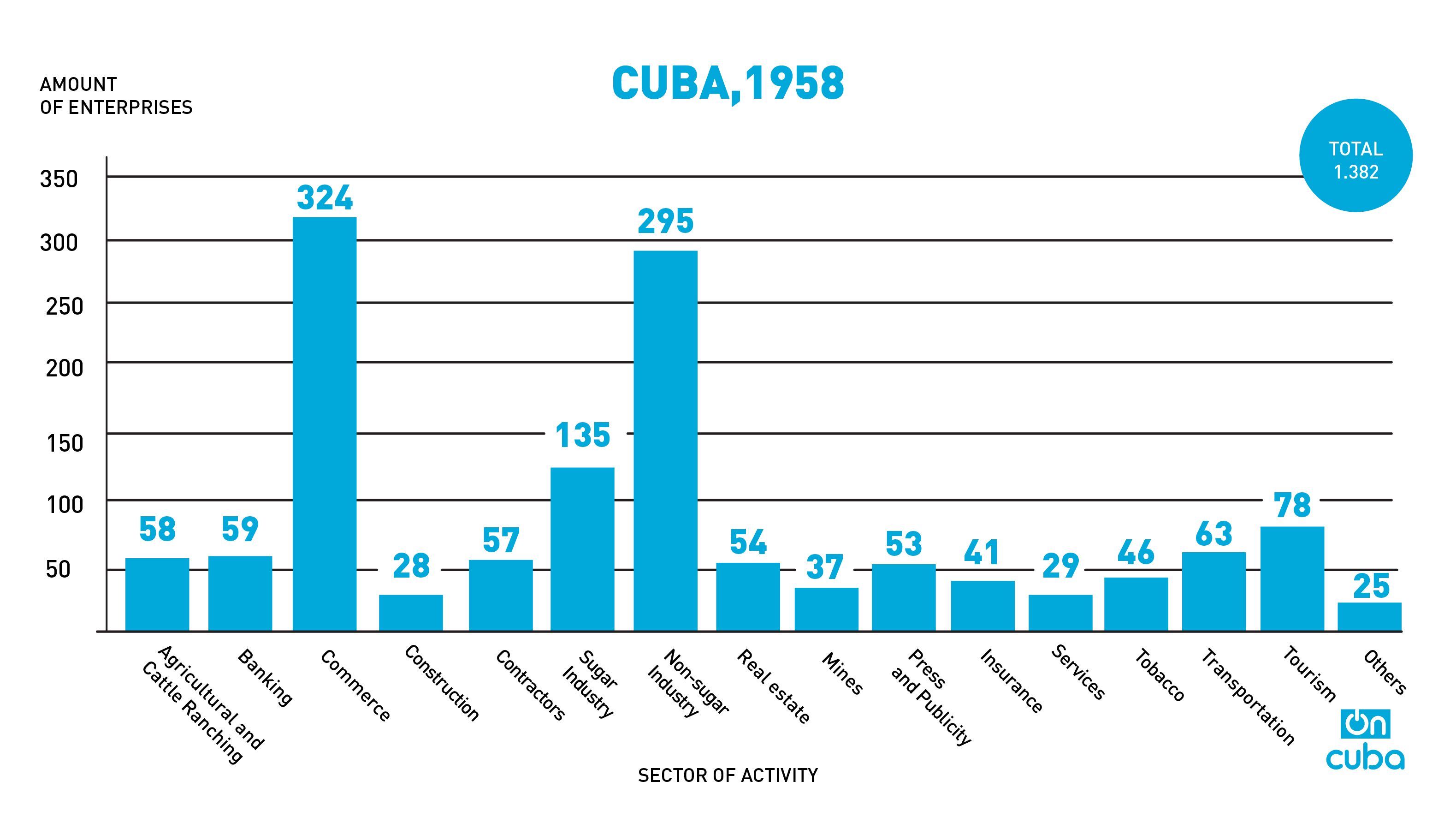

We need to know history, let’s look for a picture of that entrepreneurial world.

Obviously they are not all here; only the most significant are included. Regrettably we do not have data to affirm that these enterprises represented 80 percent of the 1958 GDP, but it is possible that they are close enough to that proportion, especially if we take into account that at that time the sugar industry and tourism were our country’s two most important sectors.

More would be missing in this picture. The 67,000 settlers who did not own the land (the majority of whom were turned into owners by virtue of the Agrarian Reform Law of the Revolutionary Government), or the small retail commercial establishments – more than 5,500 and commission agents – 700 – just in Havana are not in the picture [3], but they amounted to 20,000 [4] in the entire country. Neither does it include the so-called “chinchales” and the home workers of the industrial sector who made up two thirds of the entire non-sugar industrial sector, nationalized later in 1968. In short, all this enormous number of private workers, micro, small and medium enterprises which were also, to a great extent, part of the people defined by Fidel Castro in History Will Absolve Me.

All of that universe of enterprises, with all its deformations, functioned under the market laws, in a very lax regulatory environment, where for example, “the Ministry of the Treasury, the collecting agency, was one of the weakest institutions, with no prestige and extremely corrupt…and while the Commerce Code in its article 157 obligated the publication in the Gaceta Oficial of the accounting balances, such a stipulation was in general unknown and its non-compliance lacked any sanction.”[5] By the way, that code is still in force.

In short, “the refusal of rulers and politicians to legislate a full organization in the entrepreneurial, fiscal or stock market field…made it easy for them to hide their shady assets through figureheads and shares to bearers.” [6]

The entrepreneurial world the Revolution inherited is as mixed as this. With higher education and well-trained entrepreneurs in a part of that entrepreneurial (questionable) system and others, a great deal of them a majority, with little knowledge about management and an elementary instruction, fundamentally practicing “management through intuition” and who to a great extent, above all in that segment of micro, small and medium enterprises, survived day-to-day, with low technology and without innovative concerns, except for rare exceptions.

The entrepreneurial world was also the scenario of controversies that were never overcome, like the one that existed between an entrepreneurial sector interested in producing for the national market and that other whose principal interest was to enjoy all the possible privileges to import, fundamentally from the United States, the majority of the goods the country needed and that given their political power and ability to obtain “privileges” would be constantly cutting back from the others is possible.

With the triumph and advance of the Revolution not only is the bourgeois state apparatus destroyed but also the entrepreneurial world previously created. Partly due to the logic of the application of the Moncada Program, partly due to the reduction first and later termination of the economic and financial relations with the United States and the establishment of the blockade; also partly due to the start of the building of socialism in conditions of underdevelopment and also because of the expansion of a “romantic” vision of how to build it. Those entrepreneurs also disappeared in a high percentage because they left the country, or because they were not politically trustworthy to manage the nationalized enterprises, etc.

From that multicolored and diverse entrepreneurial world we passed on to another, conditioned by external (U.S. blockade and economic isolation) and domestic (construction of a socialism very close to the Soviet one….) factors, much more homogenous, whose leading figure has been the socialist state enterprise, which rapidly gained a space until it practically became the only one, a situation that only changed a bit over 20 years ago.

We will return next time to that other part of our entrepreneurial history.

Notes

[1] Zanetti O. In Las empresas de Cuba 1958, Jiménez Soler G.: Prologue

[2] Jiménez Soler G. In Las empresas de Cuba 1958. Ciencias Sociales publishers, 2014.

[3] Jiménez Soler G. Pág. 7

[4] Castro Ruz F. History Will Absolve Me.

[5] Jiménez Soler G. Pág. 11.

[6] Idem.