Photos: Alain L. Gutiérrez and Archive

The Cubanacán Art Schools, home to Cuba’s University of the Arts and various specialties of the National School of the Arts (ENA), are one of the most outstanding examples of contemporary Cuban architecture.

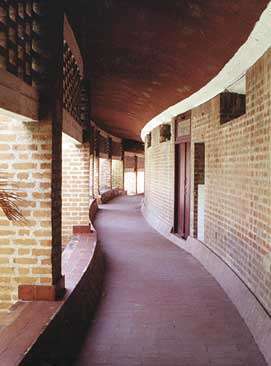

The complex was designed with an impressive visual richness. The green of its vegetation combines with the red of the bricks used in the various buildings, creating a perfect harmony among the installations and the natural environment.

Its architects, Cuban Ricardo Porro and Italians Vittorio Garatti and Roberto Gottardi, began this project in 1961, when the Cuban revolutionary government decided to build a complex for arts education on the land of the former Havana Country Club golf course.

Each architect worked independently. Porro oversaw the schools of Fine Arts and Modern Dance; Garatti, those of Ballet and Music; and Gottardi, the Faculty of Dramatic Arts.

According to Porro, they agreed that all of the buildings should have a common spirit (organic and not in the Bauhaus, Le Corbusier or Mies Van der Rohe styles). They were to be like living beings. But each architect would have total freedom in conceiving his designs.

The three architects moved into the building that previously housed the country club’s management, and from there, supervised construction work as it progressed.

The materials used were the same for all of the schools: brick and ceramic tiles, employing the Catalan vault technique. For that, they had the experience of Gumersindo, a master mason who was an expert in this method, and who taught it to the Cuban workers.

The different art faculties began to take shape. Their creators designed them as small, independent cities that interconnected through the natural environment itself.

For example, the entrance to the Faculty of Visual Arts, has three arches that extend into a narrow street with arcades that lead to a central plaza, around which are the entrances to the painting, sculpture and engraving workshops. It was inspired by the image of Ochún, the goddess of fertility. The workshops seem to made in the shape of breasts, and the central plaza’s sculpture, like a papaya, a fruit that in Cuba connotes the woman’s sexual organs.

In the case of the School of Modern Dance, the vaults at the entrance and in the dance halls are an image of exaltation. They are topped by divided cupolas, like sails inflated by exploding space. The smooth white walls surrounding the halls are as tall as two dancers who serve as a background. Columns lining the street that leads to the central plaza and circling the plaza point in different directions, creating a sense of restlessness. The small plaza and steps at the entrance, as well as the building as a whole, have the form of a splintered piece of glass, broken by a smashed fist.

In designing the Music School, also known as “The Worm,” Vittorio Garratti, says he thought about a space where every student would have an individual cubicle for studying. Each cubicle communicates with the others through a long, narrow hallway in the form of an alley, interrupted by small plazas with benches and small steps, which also serve as spaces for leisure. The “Worm” winds around the River Quibú, and from its windows on both sides, one can see the lush vegetation.

The Faculty of Ballet uses the uneven terrain upon which it was built, so that the roofs of the classrooms serve as open-air corridors from which one could observe rehearsals in the small theater, through roofs that look like handkerchiefs suspended by their four corners. The principal theater is probably one of its greatest achievements, with a skylight that projects the sun’s rays through a glass cupola.

According to Gottardi, the Faculty of Dramatic Arts was born with the awareness of a small community with a common objective: doing theater. The spaces function independently from each other, but they all converge at the same time in the theatric spectacle. The formal classrooms are on the outside, and the workshops are inside. The theater was conceived so that it could be transformed into an arena theater, with the public around the actor, and with flexible spaces so that it would function according to the kind of play that was being produced.

The construction process for these jewels of contemporary architecture in Cuba lasted until 1965, when the project came to a halt because of economic circumstances. As the years went by, many of the buildings became deteriorated. A little more than a decade ago, the long and difficult process of restoring them began. Slow step by slow step, due to the complexity of this process, some of these buildings have begun to be restored. The rest were declared museum-worthy ruins, in an attempt to maintain what time was able to preserve.