Before the birth of the Republic in 1902, the inhabitants of Cuban port cities were the victim of the outrages of the U.S. Marines who called at port in the largest of the Caribbean islands. Havana, Matanzas, Santiago de Cuba, Gibara and Caibarién were among the localities “besieged” by the Marines on “goodwill” visits or to adjust the screws during their maneuvers and training trips.

Until the triumph of the Cuban Revolution in 1959, Uncle Sam’s envoys were linked to alcohol, drugs, prostitutes, gambling and other degenerate acts, and they were the ones who caused sensational fights that were difficult to forget.

Parque Central events

In 1949, the “cordiality” government of Carlos Prío Socarrás was abounding in gangs, shortages and the black market, the assassination of union leaders and a fierce censorship of freedom of the press. Even so, the ruler of the Authentic Party was still missing the culmination: that some Marine “pranksters” desecrate the statue of José Martí in the Parque Central.

On March 10 the Palau aircraft carrier, the minesweepers Rodman, Hobson and Jeffreys and the Papago tug boat, belonging to the U.S. Navy, anchored in the port of Havana and, on the following day, at around 9:00 p.m., its sailors set foot on land and carried out, as good napoleons, an affront to the image of the National Hero of Cuba’s independence.

Hoy, the Popular Socialist Party newspaper, gave a rather exact view of what happened:

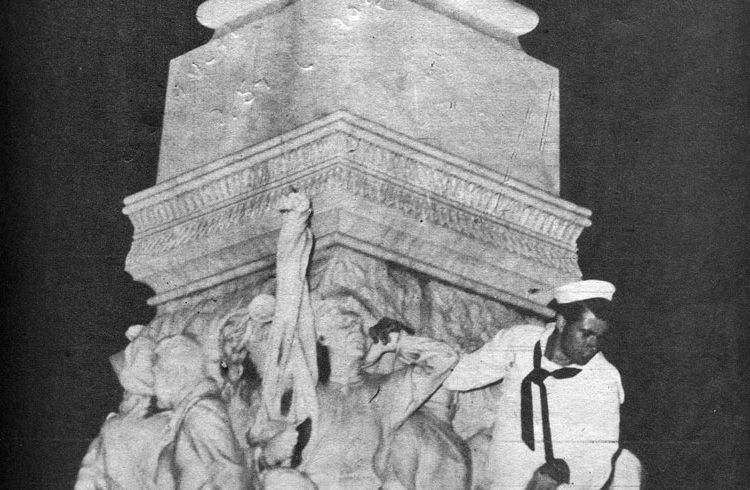

All of a sudden, a large group of Marines arrived in the park in a partying mood. Like in a race track, the brave members of the Navy started running, jumping and shouting all sorts of things. That innocent pastime by the visitors was welcomed by the regulars with an understanding smile. They continued making athletic jumps and, all of a sudden, one of them pointed to the top, the head of our principal national hero. Laughing and shouting they headed toward it and, to the surprise of all the spectators of the repulsive feat, the most daring of the group of Marines started climbing with the help of some of his comrades, while the others encouraged him with their shouts and jokes.

It was a moment of great confusion. From everywhere citizens arrived full of indignation to demand that the intruder descend; but he and his comrades responded with jokes and shouts in bad taste. The event came to its climax when the offender dared to urinate from the head of the statue where he was sitting astride. The tone of the reaction heightened. Bottles and glasses, which were taken from the nearby cafés, started to rain on them. The more determined advanced toward the group. There were bilingual discussions, challenges, tumultuous brawls, fist fights and sailors splayed on the ground.

The most notorious creators of the incident of Friday the 11th were three crewmembers of the Rodman: Sergeant Herbert Dave White and sailors George Jacob Wagner and Richard Choinsgy, the principal climber. They, after staging together with other Marines a drunken party along the Paseo del Prado, headed the outrage that was just narrated. It seems that the sculpture looked ideal to show off their gymnastic skills because of its abundance of angles and its soft marble.

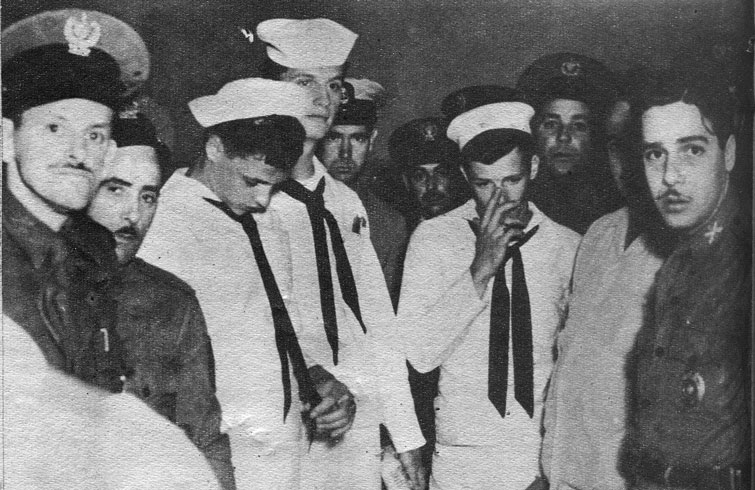

The majority of the provocateurs, escorted in a caravan by the people, afterward were led to Tourism Department of the Third Police Station, located on Dragones Street, between Zulueta and Montserrat, where Captain Pedro Delgado, the officer on duty, immediately began the due interrogations.

Hours later, government and military representatives and U.S. diplomats started arriving. Mysterious telephone calls were made, promises made and some threats were launched…. In the end, when the racket was at its peak, the naval attaché of the gringo embassy in Havana, Captain Thomas Francis Cullens, made his presence in the place and “rescued” the Marines, not before promising that they would be “severely” punished according to their country’s laws.

From that humiliation onward in the Parque Central the atmosphere became hostile for the northerners: almost at midnight, in El Dorado Café, on the corner of Teniente Rey and Prado, dozens of regular customers formed a lapidary circle around the tables of some crewmembers, who were saved from a sure lynching thanks to the action of the agents of public law and order of the zone and a patrol.

At the same time, a few steps from the current Alicia Alonso Grand Theater of Havana, a Cuban got into a fist fight with one of the Marines. When a police officer tried to separate them, the Cuban shouted: “No way, guard, I’m going to punish this one like this, as he deserves….” And he continued giving him a beating.

I’ll buy them from you!

Journalist Jorge Oller Oller in his article “The Photos of the Yankee Marines’ Affront to José Martí” narrates that when the outrage was at its most heated Fernando Chaviano went by, one of those experienced photographers armed with old box cameras who went to the banquets and, without asking permission, would photograph the patrons to later sell it to them. When he saw the unprecedented acrobatics, Chaviano, without thinking twice, used his last two plates and rapidly headed home full of curiosity.

That’s when the hunt started for that “news bomb,” as a certain gossip columnist described it.

When Pedro Beruvides, a photographer in the Romay house and temporary press collaborator, found out about the event he went to look for Chaviano and found him in his beat-up darkroom located in a tenement house on Virtudes Street, between Consulado and Prado, facing the Jhonny’s Bar. He immediately wanted to buy from him the two photographs he had shot and offered him the 10 pesos he had on him. However, the insistence made Chaviano understand that his photos were worth more and he asked for 20 pesos for them, which is why Beruvides had to run in search of the money he was missing, without imagining that his task was condemned to failure.

In the end it was Isaac Astudillo, a graphic reporter of Alerta – a newspaper located on Prado and Teniente Rey, on one of the wings of the building of the Diario de la Marina – who pulled it off.

Like Beruvides, he found out about the photos and went looking for Chaviano with a juicier proposal: 50 pesos for the negatives and the promise to give him credit for the photos he would publish.

Astudillo printed the images and handed them over to his director, Ramón Vasconcelos, and to the news chief Raúl Quintana, who, after long deliberations, decided to publish them the following day on the front page. Vasconcelos also allowed for this invaluable graphic testimony to be reproduced by Hoy and the magazines Bohemia and Carteles. At the same time, several international news agencies were responsible for spreading them throughout the world. It was a major scandal.

Of course, not only Beruvides and Astudillo were after the images. Two U.S. Embassy officials, acting as gumshoes, unsuccessfully tried to locate the photographer to offer him 2,000 dollars to destroy the terrible proof.

Several legends have been woven for years about the matter of the photos, more proper of lunatics. Some say that Astudillo, with 11 prizes in the Juan Gualberto Gómez contest that the then Association of Reported organized, tried to make Vasconcelos and Quintana believe that he also had taken photos of the Marines and that when mixing them with Chaviano’s they could have been confused.

Meanwhile, the more slanderous spread in Old Havana the rumor that Chaviano had given the Marines some money for them to climb the monument. The only thing that is certain in all this is that the banquet photographer, a humble and not very bright man, went to Alerta when the photos were already in the hand of all the people and he was given 100 pesos.

The subsequent events are more or less known: Fidel Castro, Alfredo Guevara, Baudilio Bilito Castellanos and several members of the Federation of University Students, together with many Cubans, gathered on Saturday the 12th in the Plaza de Armas, in front of the U.S. Embassy, and carried out an angry protest that was brutally repressed by the police.

Robert Butler, the U.S. ambassador in Havana, placed before the statue of Martí a floral wreath – secretly bought by the brother of Cuban Foreign Minister Carlos Hevia – and gave a speech of apology which few heard. And on Sunday the 13th, a Navy war council only sentenced Richard Choinsgy to 15 days in jail in the cells of the Rodman, a ship that fled from the island that same day with the rest of the fleet.

The sorry behavior of the U.S. Marines on March 11, 1949 was one of the saddest episodes of a Republican structure replenished of barrels of cheap rum, raving show-offs, wardrobe thieves and thugs disguised as detectives.

Historian Sergio Aguirre, the author of the work Ecos de camino, wrote in the edition of Hoy of the 16th: “Nothing has happened here. Members of the armed forces of the neighboring nation can urinate Martí’s head not fearing of the Cuban government taking the hint. Like that, as it sounds. What happened to Martí I suppose has been resolved with water, soap and a sponge, and with the floral wreath of Mr. Butler, designed to conceal, before the passersby of the Parque Central, certain smells that the statue perhaps exhales.

However, Chaviano’s photos remain as proof of the infamy.

A bit of trivia