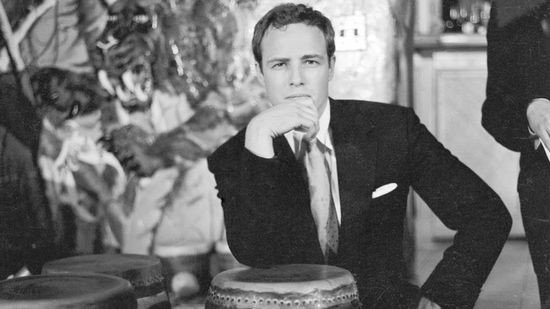

Cuban music was what made Marlon Brando board a DC3 bound for Havana on February 19, 1956. One of the most stable and systematic decisions of the cultural relations that shaped a humus with specific impacts on both shores.

In effect, a group of factors contributed to this process of reciprocal influences that has been studied by different specialists and academics, but basically possible, firstly, by Americans’ trips to Cuba, either for events or tourism, and later by technological developments, from the gramophone and acetate discs to cinema, radio and television. That is why both the son and the rumba were able to penetrate new social spaces and make possible in their own way changes in the dynamics of the body and relations between the sexes in a cultural environment such as the United States, marked by its puritan heritage and the rigidity of its axioms.

One of these correlates was the incorporation of Cuban rhythms in the dance halls, visible as early as the 1930s after the thunderous success of “The Peanut Vendor” (“El manisero”) by composer Moisés Simons, as well as the impact of the musical proposals by Xavier “Cuggie” Cugat, whose genius consisted―as Leonardo Acosta affirms―in “his ability to integrate Cuban musical languages with the familiar sounds of U.S. orchestras.” As said today, fusion music.

A little later the fury of the conga of Desi Arnaz, a man from Santiago who immigrated to the United States due to a father who was a follower of dictator Machado, self-proclaimed “the hottest guy in Havana” and “the king of the rhumba beat,” but with impacts on a way of doing that much later would be picked up by Emilio and Gloria Estefan in their time of Miami Sound Machine.

In the early 1950s, an epidemic called mambomania or mambo craze was the big success among American audiences and dancers, a sociological phenomenon that also impacted the anxieties brought about by the Korean War (1951-1953). The new rhythm, launched from Mexico City by the orchestra of Dámaso Pérez Prado, a very talented Cuban mulatto and fan of Stan Kenton, was one of the highlights of the Palladium Dance Hall, at 53 and Broadway, in the heart of Manhattan.

There were days when groups such as Machito and his Afro-Cubans played, led by saxophonist Mario Bauzá. But there were also Tito Puente (New York, 1923-2000), Willie Bobo (Harlem, 1934-1983) and Tito Rodríguez (San Juan, Puerto Rico, 1923-1973), among many others. A whole host of Latin musicians, many of whom have gone down in history for their contributions to jazz. And along with them, a generation of dancers who left an impact on the ways of doing, feeling and moving what was Latino in the United States as part of a crossover process, also visible in other domains of culture such as literature, art and cinema.

Dámaso Pérez Prado. Photo: PBS.

Marlon Brando was swallowed by that wave. In 1952 he enrolled at Alma Dance Studios, the Palladium’s academy, and took dance classes with Katherine Dunham (1909-2006), an African-American dancer, choreographer, and teacher who, at the end of World War II, opened the Katherine Dunham School of Dance and Theater, at Broadway and 43, near Times Square, after a sustained career that started in Chicago, where in the 1930s she founded the Negro Dancing Group. Professor of celebrities such as Gregory Peck, Eartha Kitt, Shirley McLaine, James Dean…, choreographer and dancer herself in the film Mambo (1954), by director Di Laurentiis, one of the hard core of the genre in the United States, alongside the famous “Mambo italiano” by Rosemary Clooney.

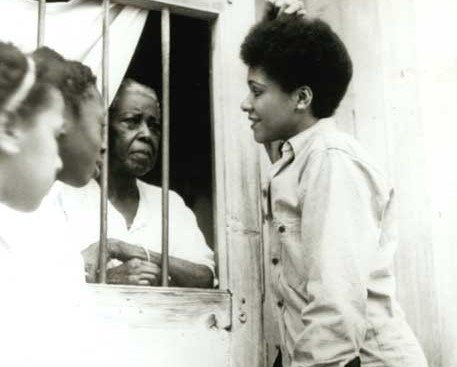

Considered indistinctly “Katherine the Great of Dance,” “Matriarch of Black Dance” or “the Queen Mother of black dance,” her work was marked early on by Afro-Caribbean influences. Her work has to be understood in the context of the processes of shaping African-American identities in the 20th century. In fact, her life and work are part of a second wave of what was black after the 1920s-30s, the latter made emblematic by Louis Armstrong’s jazz, the Apollo Theater and the Harlem Renaissance.

The 1940s-50s stand out, however, for their emphasis on the cultural impacts of the African diaspora and by increased ecumenism, in order to separate the United States from any possible exceptionalism.

Katherine Dunham in Havana. Photo: Archive.

This explains, ultimately, Dunham’s travels to several Caribbean countries—Jamaica, Martinique, Trinidad and Tobago, Haiti…—, which she visited thanks to scholarships from institutions such as the Rosenwald Foundation to undertake, at the end of the 1930s, anthropological and ethnographic studies, and in particular to investigate the role of dance in Haitian voodoo or Shangó religious ceremonies and rituals in Trinidad and Tobago.

Creations such as “Cuban Slave Lament” and “Havana Promenade” emerged from her forays and relations with Cuba, studied by researcher Rosa Marquetti. For Dunham, dance and academic work cannot be disconnected, because they form a mutually fertile symbiosis, a fact increasingly underlined by views on her work in the United States today.

Dunham and her classes must have been another of Marlon Brando’s sources on Cuban culture, music and dance, along with his relationship with the Cuban, New York and Puerto Rican performers who played at the Palladium, also called “The House of the Mambo.” The musical director of her company was Cuban Gilberto Valdés Bernal, who was with her for ten years (1946-1956).

Interestingly, in 1956, the same year as Brando’s visit to Havana, Dunham released and promoted an album, Drum Rythms of Haiti Cuba Brazil: The Singing Gods, with percussionists Francisco Aguabella, Chocolate Díaz Mena, Julito Collazo and Antonio Rodríguez. Two of its tracks, “Ñáñigo” and “Oloya de santo” are Cuban.

In short, this new emphasis on the black and African diasporic was pointing to a time of change that, at the end of the 1950s, would lead to the civil rights movement. The message underscored loud and clear, again, that Africa was neither incivility nor backwardness, but a nutritional source that had left multilateral impacts on American culture, a specific chapter in native accumulation and the plantation economy.

It is not a coincidence then that in the cinema of the 1940s-50s black actors appear in leading roles, beyond the Mammie of Gone with the Wind (character that earned Hattie McDaniel the Oscar of the Academy for Best Supporting Actress in 1939), and of the other black characters in historical Hollywood, where blacks only fit into the roles of savages, slaves, or servants, not to mention her image in racist foundational films like The Birth of a Nation, in fact, a glorification of the practice of lynching.

Dorothy Dandridge and Harry Belafonte. Photo: Archive.

Precisely between the 1940s and 1950s African-American actors and producers such as Sidney Poitier, Harry Belafonte, Dorothy Dandridge and others raise their hands and make a stand for a different approach, and above all with the need to recognize/hear a voice―or better, several—hitherto squashed/marginalized by WASP culture and racial prejudice.

But Brando was subjugated by Cuban percussion. He confesses in his Memoirs:

On Wednesday nights there was a mambo contest at the Palladium, and I was waiting for it all week. Tito Puente, Willie Bobo, Tito Rodríguez, Machito and the best Afro-Cuban bands played there. After I started going to the Palladium, I abandoned the drums and bought myself a couple of conga drums. I couldn’t contain myself when I heard those extraordinary syncopated rhythms. I was mesmerized by all of that, and every time I had to choose between dancing and playing percussion, I chose percussion.

Also:

No one who attended the Palladium could think of anything other than dancing. That atmosphere was fabulous. It seemed that all the Puerto Ricans in New York went out on the dance floor and got rid of the frustrations accumulated during the week, while working as waiters or pushing a cart in the area of the city dedicated to women’s clothing. People moved their bodies unimaginably to the rhythm of the mambo, the most beautiful dance I had ever seen.

I had always been stimulated by the rhythm, even by the ticking of the clock, and the rhythms they played were irresistible to me. Each orchestra used to have two or three conga drums, and I couldn’t sit still when I heard their extraordinary and complicated syncopations. I had been pretty good playing drums, but I had never played the conga. I gave up the drums and bought myself some conga drums.

And he closes with this statement: “The discovery of Cuban music almost made me lose my mind….”

To be continued….

TN: Brando quotes were retranslated from the Spanish.