From 1960 to 1962, some 14,000 Cuban children between the ages of 6 and 12 arrived in Miami alone, without their parents. Organized by the Central Intelligence Agency in coordination with the Catholic Church and other players, Operation Peter Pan, as it is known, was one of the most devious incidents of the Cold War and of the collision course between the United States and Cuba since 1959.

Safeguarding these Cuban minors from a supposed forced expatriation to the Soviet Union was one of the mantras of the Operation. The peculiar context was marked by the Literacy Campaign and the closure of Catholic schools; events that, incorporated by psychological warfare, had a direct impact on various sectors of the population. In particular, it influenced middle-class parents who perceived that the idea of parental authority was in crisis and therefore took on the task of protecting their children by sending them to destinations that were not always prefigured in the United States.

Operation Peter Pan began on December 26, 1960, and ended on October 23, 1962, when commercial flights between the United States and Cuba were suspended.

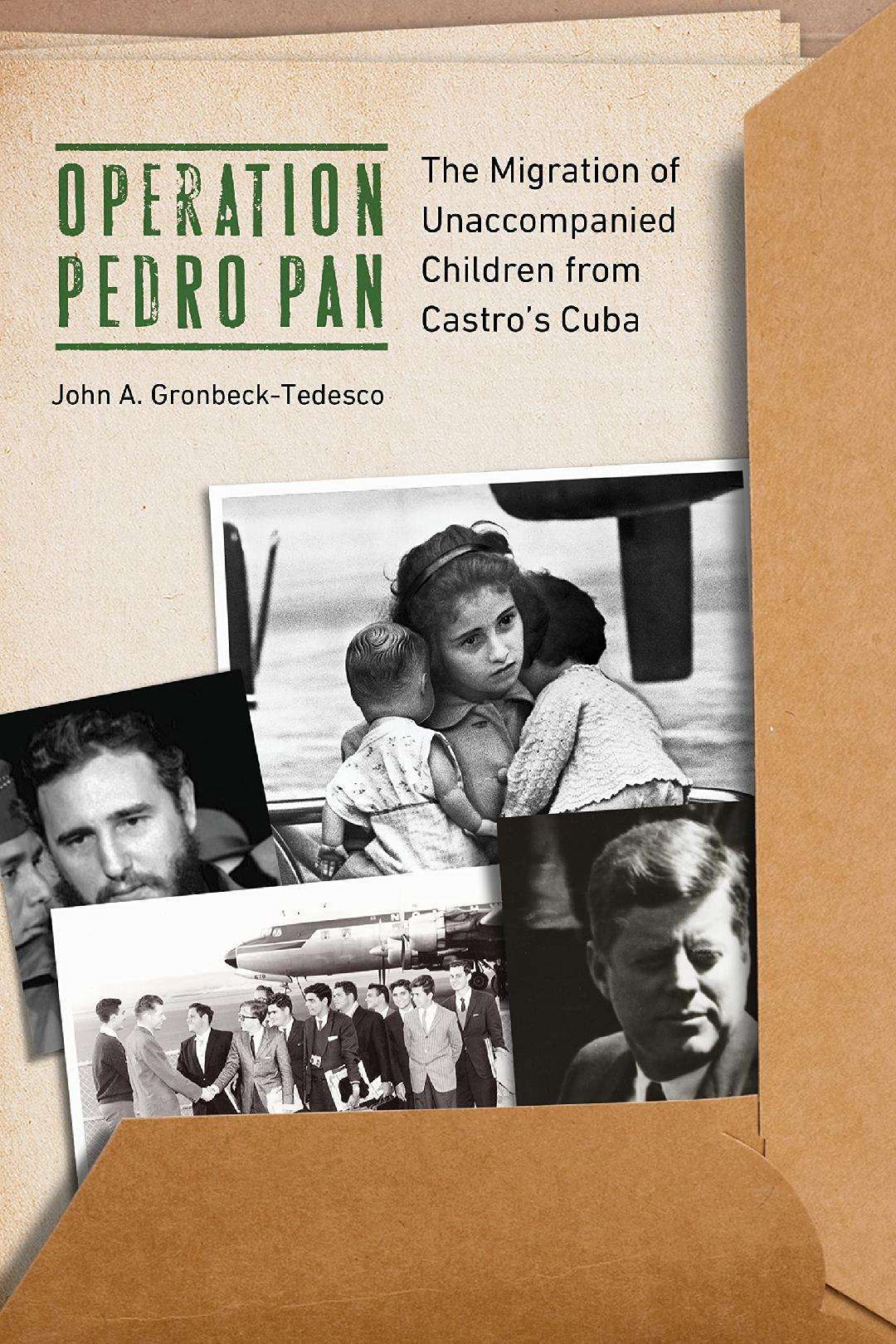

John A. Gronbeck-Tedesco, associate professor of American Studies at Ramapo College, New Jersey, has recently ventured into the history of those events. He has just published his book Operation Pedro Pan. The Migration of Unaccompanied Children from Castros’ Cuba (2022), with which he joins a trend aimed at investigating, from academia and from different angles and approaches, the past and present impacts of what is considered the largest exodus of unaccompanied minors on record in the Western Hemisphere.

Operation Peter Pan (OPP) accumulates plenty of studies and research about its motivations, characteristics, implications, and even the traumas it caused. How is this new book of yours different from the others? In other words, why and what did you write it for?

I wanted to create a broader historical backdrop for this story. There is some great work on OPP, and I make use of a lot of it, but I present new information.

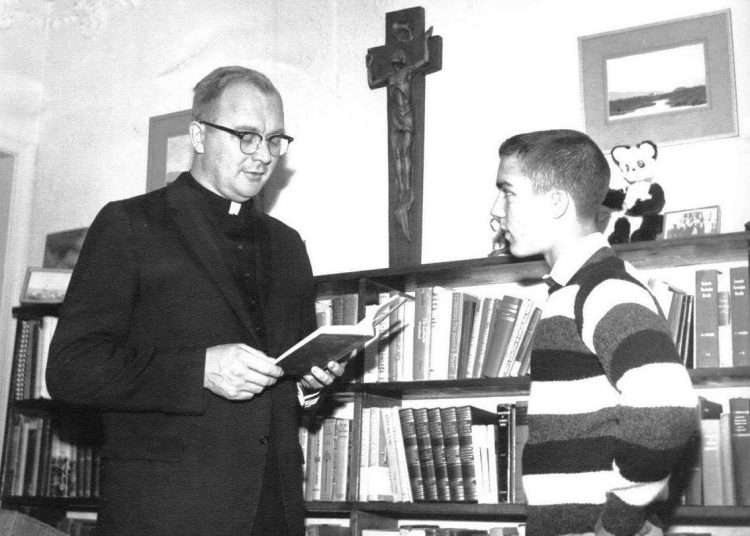

First, I spent many hours researching in Monsignor Bryan Walsh’s archive at Barry University to find out more about the administrative logistics of the program.

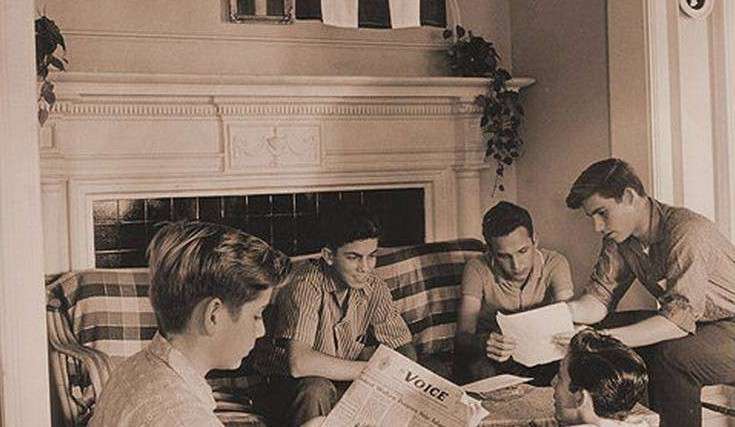

The U.S. government, the state of Florida, transitional shelters in Miami, and Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish group and foster homes across the country all took part in caring for children. This took time, money, legal resources, and the contributions of thousands to make it work.

Second, I explore more fully how child welfare was changing in the United States during the Cold War. There was a move, for example, to make more use of foster homes rather than group homes (orphanages). There was concern about raising “proper” American kids to combat communism.

American superiority was increasingly measured in the home environment, with the belief that American families were superior to others in the world and that raising the world’s children ― especially those from communist countries ― was a Cold War imperative.

Third, I explore in much more detail how Cuban refugees ― children included ― became new racial subjects in the United States. Pedro Pans arrived before “Latino/a” or “Hispanic” became official categories. Miami, a Southern city, was in the middle of its own Civil Rights Movement, when tens of thousands of Cubans showed up.

Most of them were classified as “White” in Cuba, but in the U.S. they lost that status. They were not “quite White” but not African American, so a kind of in-between racial space. Cuban children could go to White schools, but Carlos Eire, for example, remembers being told to go to the “back of the bus” when he arrived.

Broadly, Cubans could face racism in the United States that they had not seen in their country of birth. At the same time, Black Miamians were unhappy that Cuban refugees could go to White schools and that many were “taking their jobs.” Cuban refugees also could receive more federal assistance than African American citizens.

Finally, I take up the topic of changes in the Catholic Church in the U.S. and in Cuba. Catholicism was becoming more popular and widely accepted in the United States (remember that John F. Kennedy was the first Catholic president elected in 1960). Miami had just become its own diocese when Father Walsh arrived in 1958.

With the arrival of thousands of Cuban Catholics, children among them, Father Walsh and the new diocese saw an opportunity. As Catholicity was rising in the U.S., it was collapsing in Cuba. Castro confronted the Church, which was still quite Spanish at that time. So Castro could vilify the Church as a “vestige of colonialism” that still haunted Cuba. Kicking out the priests and nuns and closing parochial schools was part of the new revolutionary program.

In fact, many parents of Pedro Pans found out about the program through these schools that were closing. I also interviewed 10 Pedro Pans and 2 Civil Rights leaders for this book, which provide me with new perspectives.

From your point of view, what is the overall balance left by the OPP?

I think parents made an agonizing decision to send their children to protect them from danger. However, things did not work out the way they thought. Most believed that they would be separated for a short time. But many children didn’t see their parents for years, and some only reunited with one parent. And there are cases where children did not see either parent again.

About two-thirds of Pedro Pans needed care when they arrived; they didn’t have immediate friends or family to collect them. For the most part, their parents believed that their children would remain in Miami. Again, most thought they would be reunited within weeks or months. But then the Cuban Missile Crisis closed airspace between countries, and it became very hard to rejoin their children.

With more refugees coming every month after 1959, the U.S. government and state of Florida decided that resettling refugees outside of Florida would be a good idea. Now children were sent to places like Montana, Washington state, or Iowa. Parents sometimes did not know exactly where their children were. So larger historical events caused things to unravel beyond the control of parents, child welfare services, and of course Pedro Pans themselves.

Most Pedro Pans have favorable impressions of their transition to the United States. But there are also stories of emotional trauma, and psychological, physical, and sexual abuse. These anecdotes aren’t discussed often. Mostly there are only favorable accounts of OPP in public.

How do you see, over time, the role of the Catholic Church in this process? Did it act out of humanitarian patterns or Cold War ideology?

I answered this a bit above. I think the Church acted in both ways. Clearly, Monsignor Walsh believed that it was his divine duty to help Pedro Pans. The Catholic Church had been staunchly anticommunist since the 1930s. Part of the Cold War discourse in the U.S. was that the Soviet Union and other communist societies were “Godless.” So helping the faithful, Cubans included, was part of the Christian duty of the nation to combat communism. Catholic leaders in Cuba said the revolution had to choose: Rome or Moscow. It chose Moscow. So the Church in Cuba chose exile. Though there were some Catholic leaders that remained in Cuba with anti-Castro politics.

How would you define the insertion of the Peter Pans in the receiving society, first as children and later as adults?

Well, it was mixed. As I mention above, because Cuban children were seen as racial “others” in the U.S., they were sometimes looked at as part of the “refugee problem.” But above all Americans saw Cuban children as an opportunity to show America and its capitalism as superior to communist societies.

While doing research at the National Archives, I was amazed at how many letters I found from everyday Americans wanting to foster or adopt a Cuban child they had never met. Adoption was prohibited, but the sheer interest in Pedro Pans’ well-being suggests that acceptance of the children and their refugee compatriots was for a greater good than the negative publicity they received.

And as adults the Pedro Pan community in Miami continues to be a strong political bloc.

One of the topics I deal with in the book is the differences between the Peter Pans One of the themes I treat in the book is the differences between Pedro Pans that left Miami and those that stayed. There can be cultural differences, like comfort in speaking English, as well as political differences. Some of the Pedro Pans I spoke to found Miami Pedro Pans difficult to share political exchanges.

They are linked in their experiences and identities, but their paths toward Americanization could be different depending on where one ended up: Montana or Miami, for example.

Why did you decide to dedicate a chapter of the book to the return of the Peter Pan to Cuba?

I was very interested in when Cubans began to feel American and how they came to inhabit their identity as Cuban Americans.

The topic of the return to Cuba is one that divides the community. Many say they will not return because it would betray their parents’ decision and sacrifice. One Pedro Pan told me that to return to Cuba would betray the memory of his father (whom he never saw again) and would complicate his exile identity.

When one is an exile, he told me, one cannot return to the country of origin until the politics that caused the exile change. In Cuba, they have not, for the most part.

Yet for other Pedro Pans, returning to the house in Cuba where they were children can be a healing experience (many use the term “healing”). They feel more “Cuban” and some part of their identity is affirmed and some of the trauma associated with abandonment heals.

To what extent have the Peter Pans contributed to creating a Cuban American identity?

Pedro Pans are part of the larger exile community, but they occupy a special place. They were children and unaccompanied. Cuban refugees writ large have so many stories of difficulty and trauma. But children who came alone on an airplane or ship when they were 6, 7, or 8 years old had to confront a particular level of hardship.

Also, the issue of migrant children is in the news in the U.S., and Governor Ron DeSantis is following other Republican governors in wanting to politicize the issue of migrants in order to attack President Biden and the Democrats over the issue of border security. DeSantis authorized the closing of a detention center that housed migrant children. This sparked a controversy when the Archbishop of Miami Thomas Wenski suggested that helping today’s unaccompanied children is similar to helping Pedro Pans from the 1960s.

DeSantis then held a press conference with members of the Pedro Pan community who attested that they and their circumstances were different from those of today and the comparison shouldn’t be made. So the political relevance of Pedro Pans, particularly in Florida today, is still acute

________________________________________

Professor John A. Gronbeck-Tedesco will present his book at Books & Books in Coral Gables on Friday, April 14 at 6:30 p.m.