With Cuba’s being disconnected from the United States, a process of qualitative change of the island’s image in that country would begin. Tourism and paradise under the tropics then gave way to politics, and from that moment on the bilateral conflict has occupied practically the entire visual horizon in the U.S. media. Even though from the outset the press and television did not articulate a totally negative discourse about Cuba and its leadership, the truth is that since the early 1960s a Cuban reality made of dubious or excessive executions of war criminals of the Batista dictatorship, which had committed bloody acts generally clouded by the great mass media, was presented to the public.

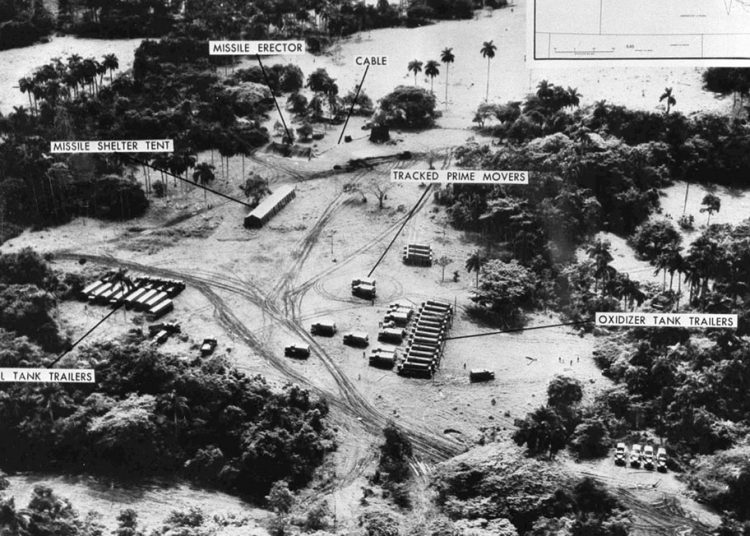

In this context, with the first desertions (Díaz Lanz) and the internal class struggle, the idea of the betrayed Revolution appeared, to which the Cold War codes were added a little later, ultimately supported by the strategic links that the Cuban system built with the Soviet Union. The island became a Soviet beachhead in the middle of the Caribbean, which was reinforced with the Bay of Pigs/Playa Girón invasion and, above all, with the 1962 “Missile Crisis”.

But towards the end of the 1970s, in the setting of a certain detente verified under the Ford and Carter administrations, there was a certain change of tone in the discourse of the American media, which illustrates the always complicated (but real) links between the press and political power. The prevailing perception underlined the idea that the Cuba of the time, after “Che” Guevara’s fall in Bolivia, had become more responsible in the new Latin American context, in the understanding that the Andes would no longer be, as in the 1960s, the Sierra Maestra of Latin America.

But it didn’t last long. The Cuban military presence in Ethiopia and Angola paralyzed this process and fed a quality of content where the labels of “USSR satellite” were practically one of the fundamental recurrences of the press, with a fixity that would extend until the dissolution of the USSR in December 1991.

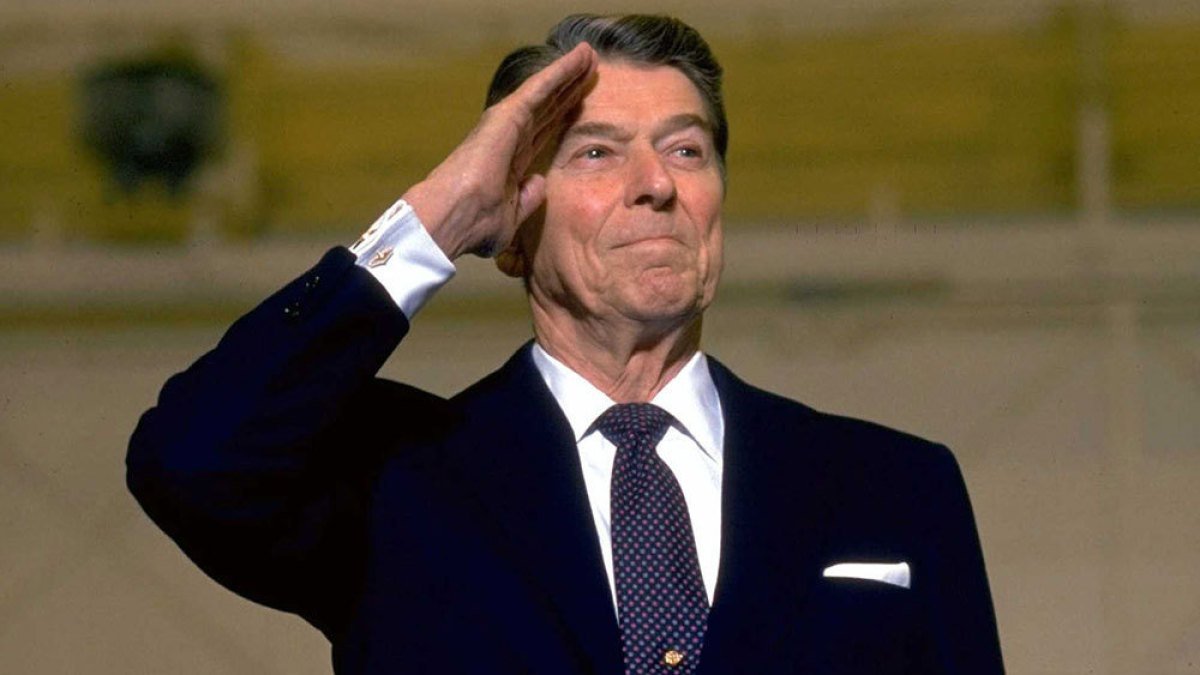

The immediate subsequent period, known as the “Reagan era” (1980-1988), ideologized like few others the Cuban issue by plunging it further into the East-West confrontation. The 1980s meant the coming to power of a neo-conservative team in the United States and implied, among other things, the alignment of the media with the figure of the president, a former Hollywood actor known for his talents as a great communicator and one of the most popular leaders of the 20th century in the United States.

With a sophisticated public relations team headed by the golden boy Michael Deaver, the new U.S. administration developed a project of world hegemonic recomposition exercising, among other things, a task of monitoring and even controlling the media, responsible for the “American lack of will.” This explained disasters such as the defeat in Viet Nam and the hostage crisis in Iran, one of the events that would put paid to Carter’s re-election. “The war was lost by the domestic enemy, by ourselves” was one of the mantras that later led to films like Rambo, a sublimation of the military defeat inflicted by the Vietcong and initiated, in fact, after the Tet Offensive (1968).

Seen from this prism, a group of measures aimed at preserving political power from unwanted information should be understood, such as the 1983 presidential directive on the obligation of federal employees to subject their writings and public information to prior scrutiny with the argument of national security. In short, early on, the administration clearly played one of its cards: the fight for control of information and against leaks to the press, expressed in threats of legal proceedings against the media for publishing “unauthorized” material and in the dismissal of officials for leaking it.

In this sense, during the invasion of Granada (1983) a new pattern was used: the monitored access of the media to the theater of operations and a rigorous information control to prevent recycling of Southeast Asia and thus try to win “the hearts and the minds” of people. The move marked a historic change since the Civil War. Since then, correspondents have reported live and direct from the theater of operations. In that context, they did it in a limited way and guided by the military.

“Reaganism,” with a very strong rhetoric, resumed the division of the world into two cotyledons: the Soviets as the “evil empire” — a category evocative of the well-known George Lucas film — versus the free world. Its regional circumstances were the inheritance of the Sandinista victory in Nicaragua (1979), the guerrillas in El Salvador and the Central American conflict, faced during its classical times with the prism of bipolarity and externalism. In other words, the causes of the problem were located not in endogenous reasons — unequal distribution of wealth, poverty and marginality, repression and political assassinations, etc. — but in East-West logic. One of the slogans of the Cold War — which alluded to the Russian threat and had even led to the massive construction of nuclear shelters in the United States — dramatically changed its geographical location: from not being detained in its “backyard,” communism was then, as the president himself announced, a two-hour flight from Texas.

In that speech, Cuba was reaffirmed as the great surrogate of the “Russian Bear” and as a recurrence: “going to the source” — that is, a military invasion of its territory — came to be the way in which sectors of the political class visualized the ways to resolve, in their favor, the Central American conflict, which in the end ended with mediation/political negotiation and not with violence.