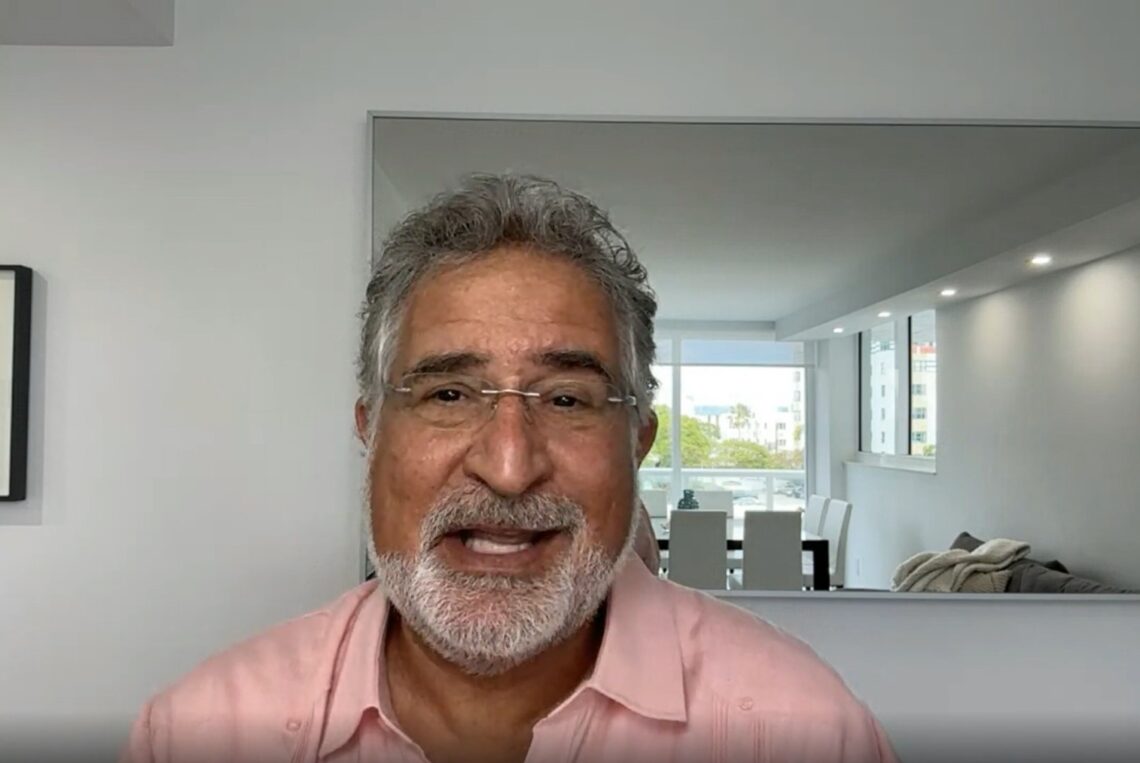

We arranged to meet via video call. Before I entered the virtual meeting, during the few minutes I waited, I noticed the profile picture of lawyer, businessman, and former congressman Joe García (Miami Beach, 1963), with whom I was going to speak for the second time in recent weeks, interested in the impact of Trump’s policies on Cubans.

I had time to decide that that photo would be the starting point for the interview. In the image, García appears greeting Barack Obama, the architect of the brief thaw between Cuba and the United States that began in late 2014 and ended in January 2017 with the arrival of the Trump-Pence administration to the White House.

“One of many,” he tells me when I mention that his photo, so political, caught my attention.

We are living in a very different time from that attempt at normalization of relations between the two countries, and I can’t help but begin the dialogue by drawing on those memories already shrouded in nostalgia.

That is probably the most poignant and everyday feeling among those of us who suffer from physical distance from Cuba. But in Miami, more than anywhere else, nostalgia for Cuba is at breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Sometimes it manifests itself through sweet reminiscences; other times, through passionate confrontations.

Nostalgia mixed with frustration, uprooting, loss… feelings fueled by the confrontational rhetoric spread by some leaders, the media, and social media influencers — not only toward the Havana government, but also directed at members of the community — fuel the growing political radicalization in the Cuban enclave.

With so much power…

Joe García was the first Cuban-American Democrat to represent Florida in Congress, between 2013 and 2015. Today, Washington has a Secretary of State and three Republican congresspeople of Cuban origin. However, this is probably the most unsettling time for the community, which sees its past privileges eroded and insecurity about its immigration status growing.

More than half a million Cubans are at risk of deportation. Of these, some 110,000 who entered under the Humanitarian Parole Program between 2023 and 2024 could lose their right to remain in the United States. For now, judge Indira Talwani has halted the Trump administration’s injunction. But it is likely that the government will appeal to the Supreme Court, where it could achieve a victory.

Cubans who entered the country with I-220A and I-220B are also in legal limbo and could face deportation. Several people have been arrested in recent weeks by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). One of the most recent cases is that of Heydi Sánchez Tejeda, who, after five years in the United States, attended an appointment with ICE last Tuesday and ended up arrested and deported to Cuba. Her husband, Carlos Yuniel Valle, denounced the case in tears, holding their young daughter in his arms.

For his part, Congressman Carlos Giménez has proposed suspending travel and remittances to Cuba and has submitted to the federal government a list of Cubans accused of being communist “agents,” “repressors,” and “infiltrators.” Law enforcement has begun carrying out arrests and deportations and is calling for the public to collaborate by providing information, even anonymously.

Giménez, María Elvira Salazar, Mario Díaz-Balart, and Marco Rubio have been described as “traitors” on a billboard placed on the Palmetto Expressway, between Doral and Hialeah. The Miami-Dade Hispanic Democratic Caucus, which promoted this campaign, said that “instead of defending our families, they have remained silent while immigrant communities are attacked, detained, and deported.”

Arguments for change

The conversation with Joe García will focus on these events. During the Biden administration, García, who was also executive director of Jorge Mas Canosa’s Cuban American National Foundation, remained very active, lobbying and supporting the emerging world of private entrepreneurship in Cuba to encourage new relationships between businesspeople from both shores. He appeared to be trying to foster arguments that would encourage the administration to change its Cuba policy.

He didn’t achieve much with the Democrats in Washington, who came away almost blank, despite multiple requests and expectations, and maintained the main features of the maximum pressure approach to Cuba that Trump had implemented in his first term.

Nor could García achieve much with the Cuban government, mired in the quagmire of a very acute multidimensional crisis, to revive new dialogues.

With Trump’s return to the White House and these Republicans, it will be even more difficult. However, Joe García insists on focusing on the opportunities. The power concentrated in the largest Cuban representation in national politics is shaping up to be a great moment. “But we have to know how to use it” and abandon “old tactics,” he says.

I almost didn’t have to say my first question. When I started talking about Obama, Joe García “connected” to 2015 and began by telling me about his first trip to the island:

Arriving in Paradise (in Cotorro)

It was a revelation for me because I had spent almost my entire career focused on Cuba. I talked a lot about Cuba, but I had never been there, and Obama’s opening gave me my first opportunity to travel. It was truly incredible. I went with my daughter because I thought it wouldn’t happen again.

It was visually shocking for me because I had traveled all over Cuba following the stories of my grandparents and parents. My grandfather was a Route 7 driver, and on the way from Rancho Boyeros to the city, I thought I’d ask the taxi driver if we could stop by Cotorro.

“Do you know where you’re going?” he said. “Yes, to the Paraíso neighborhood.” We asked a man, “Hey, where is Paraíso?” He said, “Right here,” and he got in and sat down to take us to the entrance to Paraíso. Then I described the house to him…it had these floors, it was middle-class.… There was a man standing shirtless in shorts, and we asked him, “Do you know where Captain García Mari’s house is?” And he said, “This is it. Look, the children’s names.” The house was called Margalipe — Margarita, Alicia, and Pepe — who were my grandmother’s three children.

The taxi driver said, “Come in, come in so you can see the house,” but the owner of the house didn’t invite me in. So I took a picture in front of the facade with my daughter. We got in the car and continued on. “Oh, but that’s a small house,” my daughter said. “And who told you we were landowners or millionaires?” I replied. It was an ordinary house in Cotorro. But it was a very.… You know, seeing all that all at once and sharing that…

The joy of Cubans

I went on the trip to raise the flag at the U.S. Embassy, with Secretary of State John Kerry. We were at that event and a reception at the ambassador’s home. Afterward, we went to a restaurant in one of the buildings overlooking the Malecón, and a group of prominent Cuban-Americans was there: Carlos Gutiérrez, the former Secretary of Commerce; I think Mike Fernández was also there.

There were several U.S. businesspeople — they were called “the Magnificent Seven,” because they were seven billionaires; I wasn’t part of that group. And I remember Gustavo Machín was there, whom I only knew from a photo. I introduced myself to him, and he said, “What do you think of Cuba?”

“It’s much more beautiful than I imagined.” I was a little moved.

We were living a great experience. It was incredible to walk through the city and go to that event and see the joy of the Cubans. And it wasn’t contained. Throughout the streets there was like an euphoria that had captured the place, due to the possibilities that lay ahead.

Obviously, the Cuban government wanted to broadcast that: all the buildings covered in Cuban and American flags. It was truly impressive and interesting, and I enjoyed it immensely.

In that context, I was interviewed by Granma newspaper, Cuban radio…. The cardinal [Jaime Ortega] was there; Josefina [Vidal] was there; I didn’t know her very well, but we had exchanged when I was a congressman. And many people who were familiar with the subject of Cuba.

It’s part of Cuba

Again, I thought the big mistake was that we had made this opening by leaving out one of the main actors: the Cuban exile community. Many participated, but others didn’t go; Obama didn’t force them to be part of that solution.

This isn’t a battle just between Americans and Cubans. It may have started that way, but Cuban-Americans abroad, particularly in the United States, have moved the U.S. government toward our position and our battle.

The U.S. government isn’t a neutral player; it’s, in many ways, an instrument of the will of the Cuban-American community.

Both when I speak with Americans and when I speak with Cubans, I tell them: if you don’t involve Cuban-Americans, the problem won’t be solved, because it’s not an exile community, it’s part of Cuba. And Cuba’s battle isn’t a bilateral battle; it’s also a war between Cubans.

We Cuban-Americans have a role to play, due to our economic success and our passion for this issue, and because the exile community is always being revived. Generation after generation, new ones arrive, and the exile changes.

Fifty years after the Russian Revolution, the Russian nobles who had left for Paris were already Parisians. Their children no longer spoke of Russia, although they possibly retained their Russian noble titles because of the value they gave them in France. But they had forgotten the possibility of being part of their country.

In the case of Cuban-Americans, we maintain a much more latent identification with Cuba. I myself, who am speaking to you about Cotorro and who knew Route 7 from my grandfather, without ever having been to Cuba.

Part of the mistake of the Cuban and United States governments is having tried to solve the problem without the Cuban-Americans.

MR: For decades, there has been a convergence between the interests of that exile community and the United States government, but today, fractures are emerging. The protective aura is being lost, while, paradoxically, there is more representation of that exile community at the center of federal power.

There’s a saying: “When God wants to punish you, he gives you what you want.” And no Cuban-American community has ever been more powerful than today. It may not be from my party, but I recognize that my colleagues in the Republican Party have achieved powers that Mas Canosa himself could never have dreamed of.

The dialogue of the late 1980s was a monologue by Fidel, because he had great power; many things were achieved, but the Cuban exile community was also destroyed. That power Fidel had to frame the moment and use it to his advantage also brought about the Mariel exodus and a series of events that complicate matters.

The Cuban-American National Foundation (CANF), of which I am a product in many ways, was born at that time [1981], precisely because the exile leaders had felt they had been used.

With Mariel, for the first time, there was a migration that called into question the generosity of Americans toward Cubans. In that wave, there were criminals the Cuban government released from prison, homosexuals forced to emigrate, and they arrived in a community that — without exaggerating the fiction that they were all “rabiblancos” (well-to-dos) as they are known in Panama — undoubtedly had the wealthiest people and a solid middle class.

The “rabiblancos” of the Cuban Revolution

Cuban Americans before the 1980s were almost all white. And suddenly, along comes Mariel, which makes us question each other: Are we still Cubans? Because we bump into Cubans we didn’t know. Contacts between Cuba and the United States had been very difficult. Obviously, we weren’t receiving the “rabiblancos” from Cuba.

In contrast, for example, with the immigration of the last five years, we have once again welcomed many of the “rabiblancos” of the Cuban Revolution. They are highly educated people, with previous ties to this community; people who had quasi-businesses in Cuba and properties they were able to sell to come, or who had successful families here who were able to bring them.

So, believe it or not, this latest immigration that has arrived is similar to the first if you measure it in terms of levels of culture and education. I disagree with many people on this, but I feel comfortable saying it: if the emigration of the 1960s was golden, this one is platinum, because, in addition, they are young, more educated in terms of schooling, and are technocrats in many ways, professionals, although many of them don’t use those titles here.

The golden boys of the battle against communism

The first generation, because they had such a high level of education, had a much greater capacity for integration. That’s why we Cubans arrived in a city where only wealthy Americans spent the winter and turned it into a Latin city, a year-round tourist city where you go to seek this cultural vibe.

In the 1980s, we lost control; suddenly we were frowned upon when we had always been well-regarded. We were, as the Americans say, the golden boys of the battle against communism, because we were easily absorbed; there were no limitations. And in many ways, Mariel produced that clash. That’s precisely why groups like the Foundation were created, which said: “We have to control our destiny. Fidel is setting the conditions here, not us.”

It’s true that the Dialogue created opportunities such as travel, exchanges, and the release of thousands of prisoners and their families who arrived here. But it took a while to digest. In this town [Miami], calling someone “Marielito” was an insult. And today being a “Marielito” is a source of pride: “I came through Mariel.” But it took time.

The donkey died

There’s a tendency to remember the good and dismiss the bad, but without a doubt the events of the late 1970s and early 1980s were perceived as a loss by the exile community; a weakness of ours, a victory for Fidel, although it also went badly for Fidel because the Peruvian Embassy, the Mariel, took place…precisely because his cousins from Miami, the worms, returned transformed into butterflies, and that created an internal fight.

As I was saying, when God wants to punish you, He gives you power or He gives you what you asked for. In the case of us Cubans, we asked for power, and now we want to use that power to shape Cuba based on our perspective. But the vision of an exile is not the real vision of the country.

I want them to return what was mine — which in my case wasn’t even mine, it belonged to my grandfather. I want the donkey I left tied up under the tree, and I want a Swiss-style democracy in the Caribbean. But in Cuba, first of all, the donkey died. Second, property isn’t what it used to be. And third, there are no Swiss.

“I’ll take out an eye to see you blind”

There are politicians who have been very successful in fueling envy, hatred, and resentment.

When Trump arrives, that’s when the rhetoric arrives. People forget that the presidential candidate who received the most votes in Miami was Hillary Clinton [with a margin of almost 30 percentage points in the 2016 elections, which Trump won].

If one were to design a weapon to fight a country, an embargo wouldn’t be the most effective. If I walked into a politician’s office 60 years ago and said, “I have the perfect weapon to destroy communism in Cuba. We’re going to impose an embargo that will last 65 years, but in the end, we’re going to win,” they’d grab me and throw me out a window; if they didn’t think I was crazy.

But this is what they left us… It’s like when you find a man drowning at sea; in his hands, he has a piece of wood, because it’s the only thing he could grab, and he won’t let go because there’s nothing else to grab.

They left us a law [the embargo] that the Americans put in place because their property was taken from them and it was to punish Cuba. And we [Cuban-Americans] took that weapon, bad as it was, and we’ve used it, tightened it, changed it.

One of the Cuban negotiators during Obama’s time told me: “The Americans didn’t even know all the things they had done to us with the regulations.”

I sometimes compare foreclosure to a divorce where you tell your lawyer: “Well, I’ll give her half the house, I’ll give her this car, but I want the cat.” The lawyer tells you: “But you don’t like cats,” and you say: “Yes, yes, but she loves her cat and I’m going to torture her.” Do you know why? The things we do are even perverse; sometimes they hurt ourselves, but we think: “I’ll take out one eye to see the other blind.”

The old tactics

With many of these policies, particularly what Carlos Giménez is now proposing, we would be the only country in the world where I can’t go see my family and friends, I can’t send aid…

At this moment, which should be a great victory for us [the community, the exile community], we realize how difficult it is to do what we want, even if we have all the power in the world.

We don’t have the power to convince a member of the Politburo or the Cuban Council of State to be a capitalist or a democrat because I want them to and because I have the power. Life doesn’t work that way. Fidel had all the power in the world over Cubans, and yet here we are.

So we return to the old tactics — all Carlos Giménez can come up with is that — and there are also some who don’t say it publicly, but in private: they would love for the U.S. Army to resolve the Cuban issue for them.

But the Americans also know that doesn’t work, and almost all the sophisticated players in this issue know it. Cuba is not a threat to the United States, no matter what they say to justify more military spending.

Coming to power and not knowing how to use it

Cuba historically had anti-U.S. political rhetoric. However, the Cuban people were never anti- U.S. Anti-Cubanism here also works very well, but the reality is the opposite.

You can’t say here that everyone is against Cuba and that what we want is war, when you have 20 flights a day going to Cuba and the largest trade with the island since 2014 just happened a few months ago. [U.S. food exports to the island in February 2025 were the largest since March 2014.] And almost all of those exports are being financed and managed by MSMEs in Cuba, which didn’t exist five years ago, and by Cuban-Americans and U.S. companies.

The problem is coming to power and not knowing how to use it. The more than 60-year embargo has not been effective, except that there is a team of people whose policy, in many ways, rests on the embargo and uses it as a weapon to achieve political success here [in Miami], something that obviously brings pain and suffering to Cubans.

This allows the Cuban government to avoid solving the problem. You tell me there’s a hole in the roof of your house and water is coming in, but you start working on the floor instead of the roof because you don’t want to deal with that problem.

Trying to resolve the issue of Cuba without Cuban-Americans, which is where I started, is precisely what has brought us to this point, because we as a nation have not been able to find an understanding.

Breaking with traditional exile

As Norberto Fuentes says, the Cuban Revolution never demobilized: the war between Cubans was maintained by Cuba, ideologically; just as Cuban-Americans adopted the way of being more American than Americans to maintain the confrontational spirit.

This is what brings us to the conflict involving María Elvira Salazar, who finds herself at the crossroads of representing Cubans, but has committed to this [Trump] administration to deport Hispanics, even her own people. She is breaking with traditional exile.

In my case, I traveled to 17 countries to bring Cubans; it was an exile that fought so that those from Mariel could come, those from Guantánamo, those who were imprisoned. Exile has always been on the side of the immigrant, our brother.

Now our politicians look with indifference on the suffering of people among us who are going to be sent back to Cuba.

Our politicians are faltering

They would return not to an empowered leftist revolution, but to the mess left by the mismanagement of a country. This is the first time we’ve seen this government [of the United States] do things this way, particularly to us. It’s like telling them: “Go to Cuba and wait for the economic war.”

They’re going to do it with us, the pretty boys, the golden boys of the Cold War. Now they no longer want to have anything to do with us in many ways, and our politicians are faltering. Their absence hurts, as does their silence in the face of this violation of a right that the Americans had always established for those seeking freedom.

Now, the Americans won’t be able to send half a million Cubans to the island without Havana accepting that it can be done.

I think we’re still Cuban enough to realize that more suffering isn’t going to bring what we’re looking for; and I have to imagine that Cuba’s leaders don’t wake up every day thinking about how much harm they can do to the people, but rather they try to do the best they can within a context and a system that is irreparably broken.

And I don’t have to explain this to Cubans; they see it.

Because you can blame everything that happens in Cuba on the embargo, but it seems to me that there comes a moment when you realize that, for example, not collecting the garbage in Cuba has nothing to do with the embargo and everything to do with the government’s incompetence.

MR: Since January 20, there have been some demonstrations — still few — of confrontation with the Trump administration’s hardline anti-immigrant stance. What’s happening with the Cuban community that voted overwhelmingly (55% in Miami-Dade) for him in the last election?

There’s a shift that’s happening every day.

A man told me the other day that he had brought five or six relatives. He helped pay for their arrival here. They arrived and have an I-220A. This man told me that they had already returned almost all his money, working. “They re-Cubanized me,” he also told me. This is a man who left Cuba many years ago, but maintained ties with his family and, when he saw the opportunity, used his considerable capital to get them out. He says: “I can no longer think about living without them for the rest of my life. I’m going to hide them, but I’m not going to return them because they’re part of me, they’re my family.”

I have a friend who brought her mother when she was 80. And I thank the United States, thank Joe Biden, for letting her bring an 80-year-old woman. I know that that daughter, who is a hairdresser, isn’t going to send her mother back; no matter what U.S. law tells her, because that would be inhumane.

So you’re looking at those things and you see the crazy people making money by rubbing salt in the wound. They tell you: “Well, these bread-and-steak people, these Cubans who came to eat, we have to send them back, and when they get to Cuba, they’re the ones who are going to make the revolution.”

You idiot, you go over there. If you think that, get on a plane with your sombrero and your stupidity and go confront the Cuban government. But you’re not going to send my family as cannon fodder to prove your theory of what a different Cuba can be.

Choose your enemies

They’re telling Cubans to forget that they’re Cuban, to forget what Cuba is, to forget their ties, their love, to put their struggle above that.

It’s the same problem that brought us here: that the Revolution was more important than the love I had for a brother. The Revolution was the most important thing in Cuban society. And what we found was the opposite: that here, American society didn’t force you to do anything. But suddenly, when they [the Cuban-Americans] have power, they want to force you to suffer here instead of there, for the same reason.

Choose your enemies carefully, they say, because, ultimately, you’ll be more like them than others; because in the struggle, one begins to adopt the techniques of one’s opposite.

The Cuban Revolution divided the Cuban family. And now there are some political leaders here who want to do the same thing so that their concept triumphs.

This means the collapse of hope on both sides. Just as one realizes in many ways that the Cuban government can no longer offer hope, one also hears it in the rhetoric of Cuban-Americans here.

MR: With only 90 days in the Trump administration, and seeing the conflict he has sparked with most of his decisions, not just on immigration issues, what will happen in the 2026 midterm elections? How might the Cuban vote behave?

I’m not going to start having expectations and speculating about U.S. policy in 2026. Because in politics, that’s an eternity. But our politicians need to speed up because a very strong force is building against them and against their negligence in the face of the interests of those Cubans among us.

Congresspeople don’t just represent their voters; they represent everyone who lives in their grounds, because not everyone voted. Not everyone has the right to vote, but the decisions you make as a congressperson affect everyone who lives in your grounds.

And it’s becoming clear that Cubans are asking their elected leaders difficult questions, because one thing is a Cuban I don’t know, who was deported to Cuba from a prison in Atlanta because he committed a crime, and another is a brother whom I brought from Cuba after much suffering.

That reality will have an impact in 2026, just as Obama’s policy had a great impact on this community and changed many minds — who then changed again because they didn’t see the hope they were seeking.

Cuban-American politicians are at a crossroads that, precisely, invites the possibility of finding a space for negotiation, of being able to find a broader solution.

A third path

There may be a third path that we can all take together. We won’t arrive at the same place at the same time, but at least we’re beginning a journey as Cubans toward that Cuba that belongs to all and for the good of all.

On the other hand, I know, from what we’ve seen in recent years, that if they open a small crack to Cuba, the entrepreneurial success that every Cuban brings as part of their culture can benefit the Cuban people and create a bit of understanding.

I don’t spend my life fighting with people in Cuba, with the Cuban government; I can tell you that we’ve even made friends with people I thought were deep enemies. They may be my ideological opponents, but many of them have children and family in Miami. Before, I spent my life trying to educate them politically about Miami and what was happening here. But it turns out they know Miami as well as I do.

The easiest thing in life is not to change. But if we’re going to find a solution, I have to learn other methods. Being old and mature means knowing that you don’t know everything.

We have to implement a different concept of nation.

The other day I saw Díaz-Canel talking about immigration, and he tried to be understanding within his political space. But if he’s the president of Cuba, the president of all Cubans, whether we like it or not, he also has to act in the best interest of those 500,000 Cubans they want to deport from here. And I don’t see that from Cuba either. Worse, I see a government trying to use this as a political opportunity.

Convincing those in Hialeah

The Cuban government is trying to find people in the United States to join the fight against the embargo, trying to convince 350 million Americans that the embargo is bad, instead of convincing 500,000 Cuban-Americans. Honestly, that’s a ridiculous strategy they’ve followed for decades.

Why not go to Hialeah? Why not approve visas for people more quickly? Why not offer them land [to Cubans abroad], like you’re offering the Vietnamese, to produce in Cuba? No, they can’t because that would mean facing the hole in the roof.

You don’t see an initiative that truly solves the problem. That’s why the Reorganization has been such a disaster: for not recognizing basic elements that involve the Cuban exile community. And the concept of SMEs is so hated by the historical revolutionary nomenclature that it doesn’t allow SMEs to solve real problems in Cuba.

Taxes are the most intelligent creation. Governments receive benefits without investing. The Cuban government hasn’t been able to learn that. Every time it finds something that works, it embraces it to kill it, out of incompetence. Governments make laws, regulate, redistribute, but they aren’t entrepreneurial. Just as we previously talked about the sales success of imports last February, most of which were made by SMEs, it must also be said that the number of SMEs is decreasing.

The other day, the director of AUGE, Oniel Díaz, who is a brilliant man in Cuba who is fighting for that space, spoke about this. How is it that at a time when what we need are more SMEs, there are fewer of them because it’s more difficult to obtain a license? Absurd. That’s where we are.

MR: With your experience as a congressman of Cuban origin, what advice would you give your colleagues? What would you do to adequately represent Cubans in South Florida in Congress during this time, with Trump in the White House?

Well, I’m not there precisely because I’m not preferred by the majority of people who live in South Florida. So it’s going to be hard for them to accept the advice I give them. But I would tell them they have power, but power is used to change things.

You can’t say, “Well, we’re going to bomb Havana until the communists surrender,” because people I love live in Havana, people they love live in Havana, and families of their constituents [voters] live in Havana.

When you have power and with that you can affect the game, you have to tone down the rhetoric.

I would suggest that congresspeople of Cuban origin be rational. Trump likes to say he won. And those who have been able to negotiate with Trump let him say what he wants, and then they say what they want. In politics, you have a primary and a secondary audience. And you have to realize that Trump’s megaphone is very big. When he says he won, it reaches everywhere. You have to know how to negotiate with someone like that.

In this negotiation, to end with a solution and for everyone to be happy, both sides of Cuban reality must be involved. There is room for success. But the rhetoric must change. Now, if for me winning means killing the other, then there’s no way.

Justice implies the future. Revenge doesn’t. Revenge doesn’t care what happens the next day.

When you negotiate with a brother, you don’t always win, but it’s your brother. We have to look at Cuba the same way; we won’t get everything we want, but we have to realize we can get a part of it.

I think no one in Cuba will intend to continue living in the conditions they live in today; that being Cuban shouldn’t imply destitution; or that a child tells you they want to be a foreigner when they grow up. It’s a very sad thing, and again, when hope is nullified, imagination is limited.

By limiting imagination, there is no path to the future. And we must find that path because it belongs to all of us.

We must aim for small victories that we can celebrate, so that the greater Cuba, the Cuba to which we all belong, is protected precisely by those small acts of trust, hope, and brotherhood, which can create the Cuba of the future.

MR: If you were part of a negotiating group created right now in our imagination, where the Cuban government, the Cuban community in the United States, and the U.S. government would sit, what would you ask of each of those actors?

As a first step, to remove what is harsh and damaging to the Cuban nation, Cuba should release political prisoners. In response to this concession, the Americans should say: “Well, look, for you doing that, we are willing to welcome them and their families here, not by force. And as a reward, we will remove you from the list of state sponsors of terrorism, and with that making it possible to make a little bit of money to help civil society.”

Also, by presidential decree, I would tell them: “We are going to lift all embargo restrictions on private enterprises in Cuba, businesses, SMEs, ventures that are not associated with the state, as a step in good faith on our part.”

The Cuban government should use that opportunity to say: “Okay, fine, here are Americans we have in Cuban prisons; we’ll return them to you.”

But look, I know my limitations; I’m not imaginative enough to know how to solve this problem, because there are many emotions involved.

But I do know that what I think about Cuba today is different from what I thought the last time I was there; and it’s different from the first time I was in Cuba, and it’s definitely different from when I was at Mas Canosa’s side at the Cuban American National Foundation. And if he taught me anything, it’s that leadership involves taking responsibility. A leader has to know when to stand alone.

A leader has to know how to distinguish between leadership and populism. Here [in Miami] we’ve lost that perspective. Obviously, attacking the Cuban government is popular in Miami.

If I haven’t been as critical — as my brothers here would like me to be of the Cuban government — it’s precisely because I talk to people there, and I know that doesn’t benefit me in having that conversation. Just as when people from the Cuban government deal with me, they hold back their anti-U.S. rhetoric and aren’t as critical.

We have to realize that rhetoric and reality are very different. And we Cubans are the masters of rhetoric. When you ask a Cuban to recommend a doctor, they say, “I’m going to recommend my cousin, who is the best doctor in the world.”

Look, in Miami we’ve created a virtual Cuba; in many ways, this is the northern part of Havana, and in any other context, that could be one of Fidel Castro’s great achievements: sending a group of his nation’s children to the most advanced country in the world. If they can return to their homeland, as happened after the Babylonian captivity of the Jews, their homeland improves, it is reborn.

I’m not saying that Cuba doesn’t maintain Cuban culture; that remains in Cuba. In Miami, one of the great tragedies is that we have nostalgia, not culture — a deep love — and when new inputs come, we reject them at first, but then we realize they’re like us, and then we love them.

We’re here preserving the Cuba that was, not the Cuba that is. And we’re part of that. If Cubans there lived like we Cubans abroad, it would be good for Cuban culture and the nation. Let’s think about it a little: that’s all we want.

If we look to each other and trust in the small things we can do to improve the lives of Cubans, the life of the nation is going to improve.