In his autobiography, Daniel Chavarría, National Literature Award winner, cites this advertisement for an American airline in 1967:

Our staff is professionally and psychologically trained for any emergency. In the event that your plane is hijacked and forced to land in Cuba, our flight attendants will remain calm and can dispense medicine, smiles and turn the mishap into a delicious adventure. In the event of a long stopover in Havana or another Cuban city, they will be happy to organize for you excursions, visits to beaches, nightlife centers, historical places or places of great natural beauty; and all at the invitation of our company, without scaring you or costing you a single extra penny.

Chava, as he was known in the corridors of the School of Arts and Letters, where he taught Latin and Greek, had himself hijacked a small plane from the Colombian airline Avianca, and had forced it to take a course to Santiago de Cuba in 1969. He was escaping from persecution by the Colombian police and army, who had discovered his participation in a support network for a guerrilla group in Valle del Cauca, together with the Bishop of Buenaventura, Gerardo Valencia Cano. He arrived in Cuba at the end of October, with his wife and his daughter, who accompanied him in the hijacking.

Chava’s plane was one of many diverted to the island from Colombia and other countries in the Caribbean Basin. As I pointed out before, after suffering hijackings of its planes and ships, and subjected to ostracism by almost all the governments of Latin America and the Caribbean between 1964 and 1973, Cuba became a refuge for many who were fleeing from repression, of those who wanted to make a revolution in Latin America and the Caribbean, and in almost any part of the world.

While the history of Cuban solidarity with the national liberation movements awaits its historians, the topic of those planes diverted to Havana is inexplicable without its context.

Teishan Latner, a historian of the left in the 1960s and of its interaction with the Cuban Revolution, explains in an essay who were the Black Power militants who escaped repression in the United States and found political asylum in Cuba. Hunted dead or alive by the police and the FBI, some managed to hijack a plane and take refuge on the island.

In certain cases, those young revolutionaries had been involved in armed actions, in which there were shootouts with the police, and officers were killed. As they were politically persecuted and considering their ideological motivations — which Cubans did not always share, but respected —, they were very different from those who murdered guards or ship crews in cold blood to make their way to the United States, as has been the case among hijackers of Cuban ships and planes.

To a large extent, the behavior of many of the Americans who hijacked planes is inexplicable without the siege and demonization of the Cuban Revolution that the United States had imposed. Besides, that was the Cuba of the Tricontinental (1966) and the OLAS (1967) conferences, the “create two, three, many Vietnams,” the Havana Cultural Congress (1968), which renegaded Soviet and Chinese socialism, and experimented with “the parallel construction of socialism and communism.” Although it is not the Cuba of today, neither can it be understood as the mere fruit of a revolutionary imagination or a radical ideological projection, since it existed in the form of a very tangible society, political process and culture. As much as its conflict with the United States.

Even if idealized to some extent, that Cuba was not a simple fantasy of many young people of 1968, in Latin America and the Caribbean, Europe and the United States itself; nor when they represented it as the promised land of social and racial liberation, the incarnation of left-wing heresy, the anti-imperialist vanguard. Over here, for many Cubans at the time, the struggles against racist power, the preaching of Malcolm X and the organized action of the Black Panthers were the spearhead of a social revolution in the United States, which had begun by the civil rights movement. In any case, it was not at all unusual for those to have the island on their radar of struggles, as a concrete reference point and also as a sanctuary; nor that on this side they were seen as comrades in arms.

In line with the political legacy of the Cuban left, since the 19th century, revolutionaries and terrorists have always been two different species. So the nature of relations with U.S. revolutionaries differed from the climate of conspiracy, secrecy, and indiscriminate violence typical of terrorism. This was reflected in the exchanges between the leaders of the Cuban Revolution and Malcolm X, Angela Davis, Stokely Carmichael, their mutual, public and legitimate support, in terms of a revolutionary policy.

Black Panthers like Huey P. Newton, William Lee Brent arrived in Cuba; and militants from the Republic of New Afrika, such as Charles Hill and Nehanda Abiodun, political exiles, who were passing through, only to one day return to continue the fight in California and Chicago; or on the scale of a trip back to Africa, the promised land where the dream of their elders awaited them. Most left afterwards. Although a handful stayed forever.

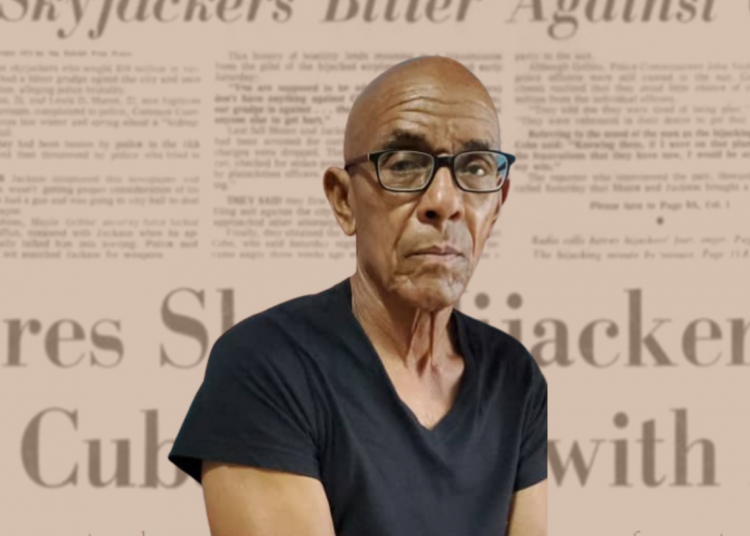

Among the latter was Charlie Hill, who has lived in Cuba since 1971. In contrast to his image on the FBI’s wanted list, he is a mild-mannered man, about to turn 73, with more than half a century on the island to date and who came when he was 21.

I asked him: And among those hijackers were there those who had no political struggle in the United States, but were taking advantage of it? “Of course,” he tells me, “there were those who were common criminals, like some who threatened to crash the plane into a nuclear plant if they were not given a ransom of 2 million. After that case, the United States prepared to sign the hijacking agreement with Cuba.”

In the previous article in the series I commented on how the 1973 MOU had been the result of persistence on the Cuban side, since 1969. However, it wasn’t so much because of that perseverance that the United States agreed to sign it, but, as Charlie says, for their own interests. Likewise, due to the situation of insecurity in aviation created at an international level. Between the Tokyo Convention (1962) and the Montreal Convention (1971) on the problem of hijackings, their heyday had managed to bring together a growing group of countries to try to avoid them.

Having signed it, however, did not force the FBI, so tenacious in its pursuit of Black Power, to tie the hands of the Cuban exile terrorists. Before and after the attack in Barbados in 1976, they continued their anti-communist crusade “on the roads of the world” as if they were loose wheels.

In the early 1980s, Cuban fishing vessels continued to be victims of piracy sponsored or tolerated by the U.S. authorities. Although in some cases the hijackers were prosecuted, they were not punished. The prevailing stance in favor of impunity among the state and judicial bureaucracy would contribute to perpetuating hijackings. In the 1990s alone, about ten planes and numerous ships were hijacked, some of which included the murder of their crew members. In some cases, the hijackers not only found refuge in the United States but were hailed as heroes.

Despite the vision that interprets the Revolution’s policy as a saddlebag of ideological apothegms, romanticisms and utopias, it would be a mistake to believe that Cuba wanted to become a center for the export of the revolution, also to the United States, in the 1960s. It was one thing to sympathize with the Panthers, and the revolutionary pan-Africanists, and another to turn the island into a headquarters for their struggles. Neither the Cuban government, nor those of Africa that emerged from the anti-colonialist struggles, aspired to be the headquarters of these movements. It was one thing to give political asylum to the persecuted, and another to encourage the practice of plane hijackings.

In addition to giving rise to adventurers or people infected by the copycat effect that criminologists explain, hijackings have been the tip of the iceberg of a larger problem: the lack of a legal and political order that structures the relationship between the United States and Cuba.

Air and naval security is one of the main components of this relationship structure between two neighboring countries like ours.

According to the Cuban government, both on the eve of Mariel (April-September 1980) and the incident with the light aircraft (February 24, 1996), high levels of the U.S. administration were informed about a probable contingency, which could trigger a security crisis; and the need to take preventive measures. The warnings went unheeded in both cases.

Although in the two events it is possible to judge the Cuban responses as drastic, they were not unpredictable. On the contrary, according to historical patterns, Havana’s reaction could have been calculated, as a function of the high risk attributed to the hijacking or misuse of ships between the two sides.

The lessons to be derived from these experiences are very realpolitik. If the Reagan administration in 1984 and the Clinton administration in 1994 sat down to negotiate immigration agreements with Cuba, it was only because they took seriously the consequences of new immigration crises. If no more “unarmed planes” nor “civilian vessels” from Florida entered the air or sea territory of the island “in peace” it was because U.S. security devices did not allow it. That is, because “a common order” was established, a practice not necessarily written, which both sides have respected.

This practice, however, is open to the initiative of anyone, as demonstrated by the hijackings of recent years, almost always associated with migratory tensions.

Imagine what could happen to a plane that was hijacked from Mexico, Guatemala, or the Dominican Republic, and attempted to enter U.S. airspace.

I asked Charlie Hill that question and he just stared at me. Incredulous.