In the summer of 1900, five warships –the McClellan, the McPherson, the Crook, the Sedgwick, and the Burnside– carried unusual “cargo” from Cuba to Massachusetts. At the beginning of July, over 1,200 Cuban teachers from across the island arrived in Cambridge to attend the Harvard Summer School for Cuban Teachers, where they were trained in topics such as culture and pedagogy. An additional benefit of this experience was their encounter with American society at “this time of splendid productivity and transformation,” as described by national hero José Martí. “Whoever names ‘Harvard,’ the great college of Massachusetts and the Oxford of North America, utters a magic word that opens all doors, [and] carries all sorts of honors.”

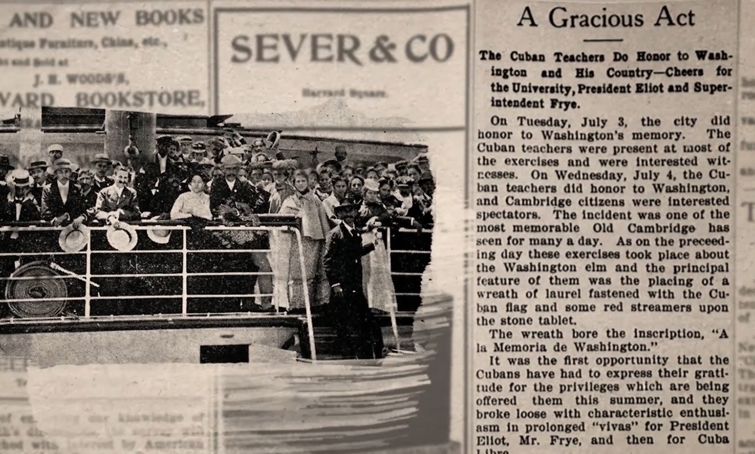

Under these auspices, the Cuban teachers, coming from towns and cities plagued by 30 years of warfare, dedicated themselves to the formation of a new republic. They enjoyed the warm welcome of their host society to such an extent that at the end of their studies, the teachers met with President William McKinley himself in Washington. According to press reports from the period, McKinley greeted each Cuban teacher by name as he shook their hands one by one.

The Cuban teachers who attended the Harvard Summer School returned to Cuba after eight weeks. They returned to a homeland still occupied by the political, military, and economic power of the United States, which would transfer the governance of the country to the Cubans in 1902 after signing the Platt Amendment, with all of the implications thereafter.

These details of the Cuban Teachers’ Expedition, rather unknown to the general public up until this point, bring the history of the paradoxical relations between the United States and Cuba to the fore. The story was given new life in the form of a documentary film, created at an opportune moment, thanks to the support of the Cuba Studies Program at the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies at Harvard University.

Los cubanos de Harvard (The Harvard Cubans), a 72-minute documentary directed by Cuban journalist Danny González Lucena, uses imagery to reconstruct a historical moment with many echoes in the present. The film will premiere on October 23rd at Harvard University in Cambridge, MA. The film will also be presented at Florida International University on November 6th.

In 1900 –during the military occupation of Cuba– this initiative, proposed to the U.S. government by a U.S. official involved in the occupation government, was viewed with great suspicion. There was concern that the expedition of Cuban teachers had an ulterior motive of “Americanizing” this group of people in order for them to replicate the culture in newly republican Cuban society. From your research, can you confirm this suspicion? How could Cuba benefit from bringing so many Cuban teachers to the United States?

1,273 Cuban teachers participated in the Expedition. Many of their signatures appear in an Autograph Book housed at Harvard. One of these signatures belongs to the teacher Ramiro Guerra. Several decades after the trip to the United States, the historian from Batabanó who would go on to be an important figure in the Cuban education system, wrote in an article in El Diario de la Marina:

“As for the United States government, it had no involvement, direct or indirect, in the excursion other than facilitating the transport of the teachers from the Cuban ports to Boston and then to New York, Philadelphia, and then back to Cuba.”

However, leading up to the trip, there was significant uncertainty about the true intentions of the Harvard Summer School. Regino Boti, a teacher from Guantanamo who would later become one of Cuba’s most important intellectual figures, was also part of the group; he wrote in the newspaper El Managuí:

“To seduce us, they offer another ensnarement, seemingly weak but actually strong and frighteningly so: the Cuban Teachers’ Expedition to the United States.”

However, when the aforementioned Autograph Book was signed, most teachers’ reckoning was similar on two matters: on the one hand, they appreciated the logistical support from Harvard University and the U.S. government in making the trip a reality, and they appreciated the camaraderie they received from the residents of Cambridge and Boston. On the other hand, they said that they would feel even more satisfied once Cuba was free and independent.

As superintendent of schools in Cuba and the architect of the expedition, Alexis Frye was a key player in this process. He was an officer of the occupation army, had studied at Harvard, and he was also a fervent supporter of education on the island. I believe that in Cuba we are indebted to him because his legacy has never been thoroughly studied. After his appointment, he opened over 3,000 schools that ultimately served 130,000 students. This was a project that the teachers saw as a positive contribution.

In the United States, the Cuban teachers also received great signs of affection from U.S teachers. Most importantly, there is not a single document –at least not that I found– that explicitly expresses the U.S. government’s intentions to “Americanize” the Cubans through their instruction during this trip.

Any remaining doubts should be clarified through viewing the documentary, but I cannot resist affirming that, to my knowledge, the trip had very positive outcomes, not just for the teachers but also for Cuban society at the beginning of the twentieth century. For example, the genesis of the feminist and suffragist movements in Cuba can be traced to this expedition.

In 1900, the United States was one of the most developed countries, and the Expedition included teachers who had never left the small towns where they lived in Cuba. This experience undoubtedly changed their lives forever.

These teachers, who represented the various regions of the country, were considered the forgers of Cuban identity and civic values during peacetime in the twentieth century. In what ways did the Expedition serve this purpose?

The great majority of the Cuban teachers who attended the Harvard Summer School in 1900 were born in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. They had personally suffered the ravages of the final war for independence, in which the United States ultimately intervened, and they professed a great nationalist sentiment. However, they did not know each other. During this time period, if one lived in Havana the opportunity to meet a teacher from Santiago was very rare, especially given that the country was struggling with the terrible aftermath of the wars for independence. It is the Harvard Summer School that brought together teachers from Guantanamo to Pinar del Río in the same place for the first time, providing the opportunity for them not only to get to know each other but also to envision themselves from an ambassadorial and nationalist perspective.

In the United States, they observed a level of development that they hoped to bring about in Cuba, but they sought to always maintain sovereignty and independence. On countless occasions they were received by the people of the United States with huge posters reading: ¡Viva Cuba libre e independiente! (Long live free and independent Cuba!). And this filled them with pride.

Everything that they observed, learned, and debated on the relations between the United States and Cuba during the visit was surely brought back to their classrooms on the island.

We can assume that their stay at Harvard left an impression on these young people. But what remained of them in Cambridge? Were they able to leave a legacy there, beyond showing off their dancing skills in danzón? What does this story teach us that we can apply to the present?

The Cuban Teachers’ Expedition to Harvard is one of the most important educational and cultural events in northeastern United States in the summer of 1900. All of the newspapers of the period were full of headlines about the Harvard Summer School.

The trip also changed perceptions about Cubans regarding race. The Americans were surprised by how much they resembled the islanders, not just physically but also cognitively and socially. Considering the standards of the era, there was a lot of tolerance for the teachers who were black and mestizo.

The elite circles of Cambridge and Boston opened, possibly for the first time, to welcome a mass of individuals of common rather than genteel origin. The Cubans were constantly invited to receptions, above all in the homes of individuals who owned property in Cuba, as was the case with the Atkins family.

However, during the first decades of the twentieth century the Expedition fell into complete oblivion, not only in Cuba, but also in the United States. Cuban poet and essayist Victor Fowler, who co-wrote the script with me, thinks that this happened because the Harvard Summer School for Cuban Teachers was not ‘monumentalized’ since it was not an official government matter in either country but rather an initiative of Alexis Frye and supported entirely by Harvard University. I agree.

The details of the events of July and August of 1900 are currently available at the Harvard University Archives. There is even information available about the trip online.

What story does the documentary tell? Where does its narrative end? What metaphors does the film employ? Who were you able to interview? Were you able to meet any of the teachers’ descendants?

The documentary narrates the expedition of the Cuban teachers to Harvard in the year 1900 from an analytical point of view. The film shows the antecedents leading to the conception of the trip, the discordant views of the true intentions of the initiative while preparations for the trip were finalized, such as how they would handle the issue of race, considering that many teachers were black, as well as the logistical planning to receive women from Cuba who were traveling alone to a foreign country and comprised over half of the group of 1,273 Cuban teachers. The film also covers the courses taught at the Summer School, the tensions that emerged from the annexation of Cuba to the United States, and the tour they took of New York, Philadelphia, and Washington, where they were received by President William McKinley.

Essentially, this is a documentary about friendship between Cuba and the United States: this trip was the most substantial people-to-people exchange that has existed for both countries. Never since has a group of over 1,000 people traveled from one country to another, forming a large delegation, in a project of this kind.

A great love story arose between Alexis Frye, the superintendent of schools in Cuba, and María Teresa Arruebarrena, a teacher from Cárdenas who joined the expedition. As part of my research, I was able to meet two of their great-grandchildren who currently live in the United States.

I also contacted Eliana Rivero, an emeritus professor in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese at the University of Arizona, and who is the granddaughter of María de Jesús Hernández, a teacher from San Cristobal who also visited Harvard in 1900.

In addition to the three individuals mentioned, I conducted interviews with: Jorge Ignacio Domínguez and Alejandro de la Fuente, co-chairs of the Cuba Studies Program at the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies at Harvard University; the historians Marial Iglesias Utset, Yoel Cordoví, and Julio César González Pagés; and Victor Fowler.

You yourself have been a “Harvard Cuban.” How did that idea come about? How did you work there? What did you leave Harvard with besides the documentary you created?

I first became familiar with the story of the Cuban Teachers’ Expedition to Harvard thanks to an article published by Yoel Cordoví in the magazine Espacio Laical. I am a fervent student of the history of Cuba, but I have to admit that I had never heard anything at all about the Harvard Summer School program for Cuban teachers in 1900 until his article. An old friend from college, Lenier González Mederos, encouraged me to make a documentary on the subject.

I was able to spend a month at Harvard, where I had access to all of the material related to the expedition of Cuban teachers. I received great support from many people involved with the project; specifically, from Marial Iglesias, who offered me a great deal of bibliographical material as well as her expertise about the subject, and Erin Goodman, Director of Academic Programs at the David Rockefeller Center, who was integral to the project and who subtitled the film for an English-speaking audience.

When I was in Cambridge, Victor Fowler was a visiting scholar at the Hutchins Center at Harvard. I told him about my project and he was very interested; upon our return to Cuba, I proposed that we conceive of the script together, and he agreed. It has been a very interesting professional relationship because we have nearly always been in agreement. He has a remarkable ability to weave together facts and characters.

The music in the documentary was composed by Cuban musician Edesio Alejandro. I am very pleased with the score. He is someone I respect a lot. His son Cristian also played an important role in the editing process. But the greatest surprise was that Eliades Ochoa, of Buena Vista Social Club, used his guitar to tell this story, composing original music for the documentary.

The narration was done by Niro de la Rúa. I have always loved his voiceover work.

The recordings were done at the Estudio Blem Blem, directed by Edesio.

I must thank the graphic designers: Camilo Suárez Hevia, Lisett Ledón Fernández, and Wendy Valladares Hernández. As a documentary with no reenactments, all of the photography had to come to life through the animation, and they did it masterfully. They are very young yet exceptionally talented artists.

What I brought back with me to Cuba after my stay at Harvard was an incorruptible truth: the people of Cuba and the people of the United States have always been friends. What happened over 100 years ago during the expedition of Cuban teachers continues happening today.

You prepared the documentary in 2016, the year in which President Obama made a historic visit to Cuba, in the midst of normalizing relations between Cuba and the United States. With the government of Donald Trump, the situation has changed. How can your documentary contribute to continue promoting a path of dialogue and respectful coexistence between our two countries?

Regardless of the political relationship that exists between the two countries, there is a history that narrows the distance. What merits further investigation is how Cuban culture, through the diaspora, has influenced the southern United States; but also, and this is rarely discussed –how the American cultural heritage remains in Cuban society.

My documentary will show the public how, despite the differences that existed more than 100 years ago, Cuba and the United States came together through their people towards a common good. Friendship is something that is built and this is what my documentary shows, from beginning to end. In a situation as difficult as the current one, we must hold that the truth that above all else.

—-

*Translated to English by Julia Cohn

Hmmm interesting, that’s why we stoped seeing him in Cuban TV.