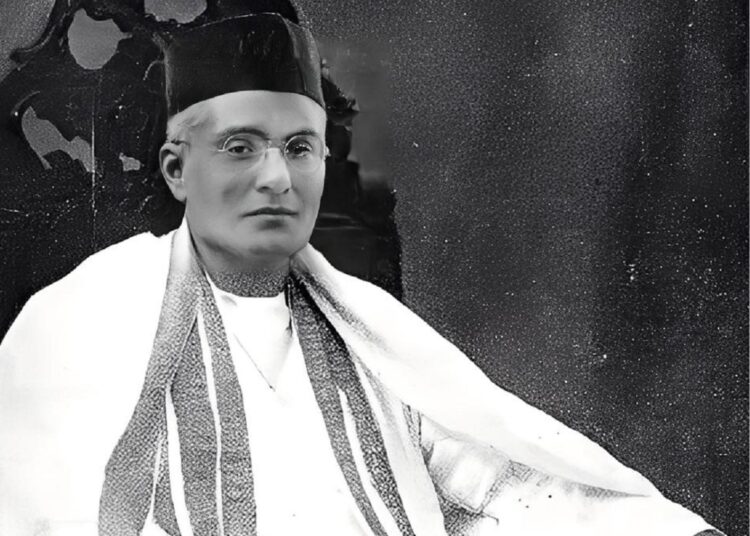

On September 5, 1929, as the morning began to color the sea, a man with a gentle smile and a head full of ancestral wisdom about the evolution of life and form arrived in Havana on the ship from Yucatán. He was dressed in a European style, with a suit, a bow tie and an English explorer-style helmet hat, a far cry from the typical Brahmin robe and the saffron sackcloth worn by sanyasis while traveling the roads. But his smooth, amber face, with prominent eyebrows and cheekbones, immediately associated him with that mythical land where rivers swept sacred rituals and men charm snakes with ancient secrets.

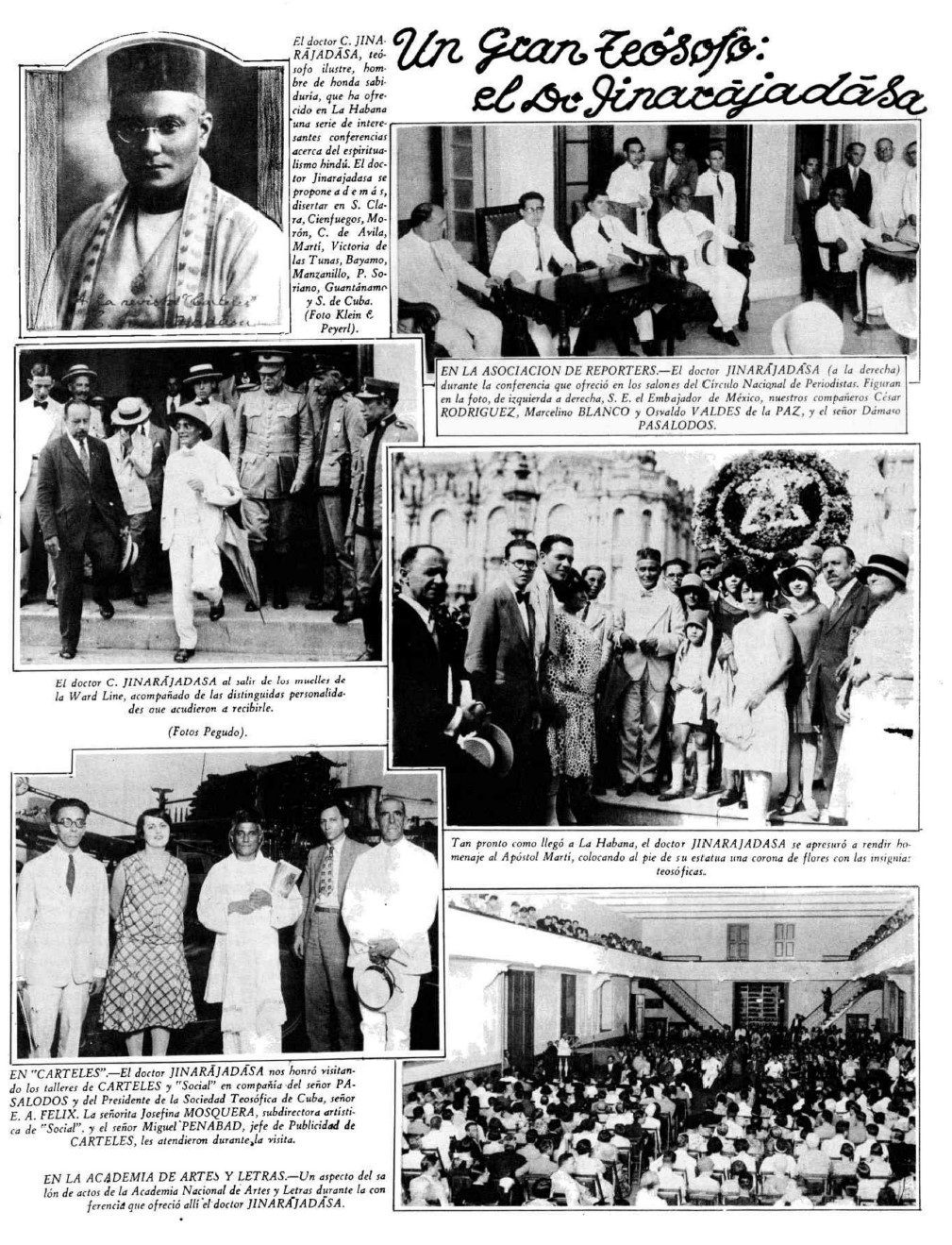

It’s no wonder he had the gift of the gab and the ability to captivate his listeners. His fame as a Hindu philosopher and great master of Theosophy preceded him; therefore, an enthusiastic entourage awaited him at the port, smelling of saltpeter and tobacco. The pilgrim understood well that all questions have a dock where they disembark, so, upon stepping onto the Ward Line jetty, he didn’t keep his followers or the press waiting to reveal the reason for his visit: “to demonstrate that there is a great future for the country and to study all the beautiful idealism that exists here and that, properly channeled, can contribute to the future greatness of this blessed Cuban land.”

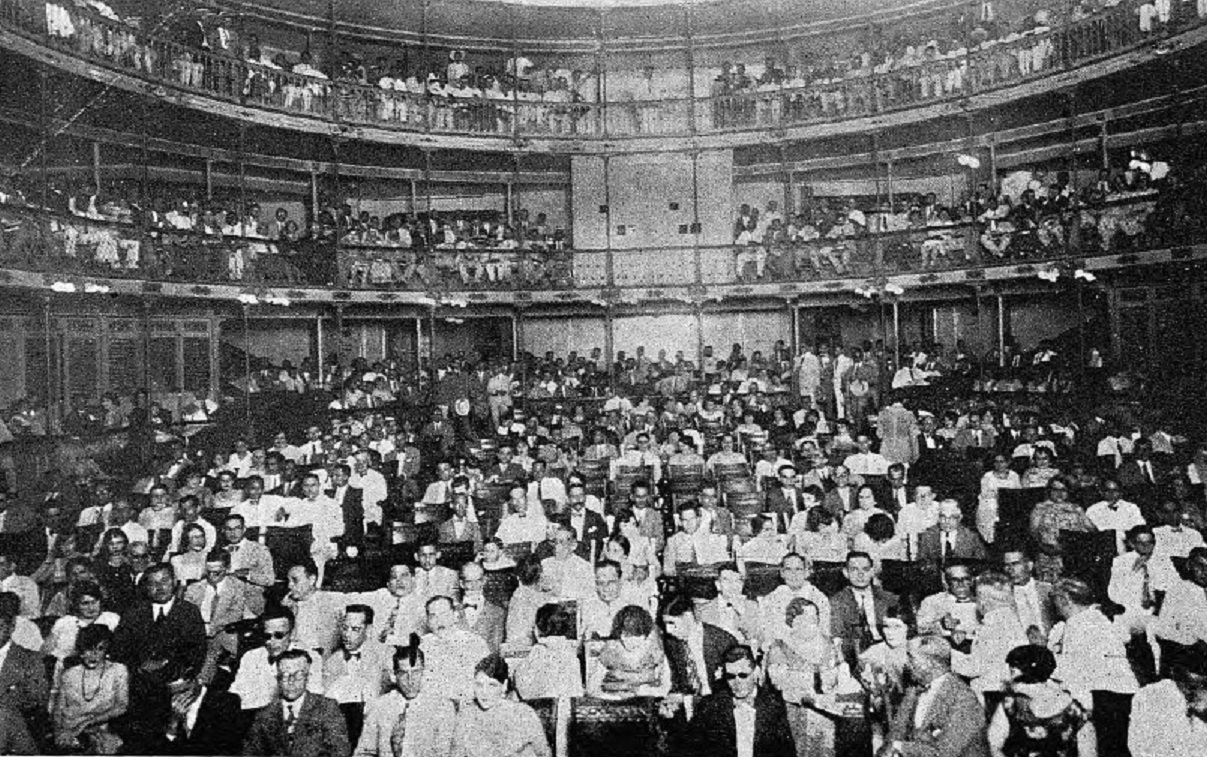

Cuba, the last stop on a year-long tour that took him through sixteen nations in the Americas, opened up to him like a book with blank pages. Convinced that to learn, one must sometimes travel without maps, he began a triumphant march through the Republic, gathering select audiences in the various auditoriums, as numerous as few could muster. It was the moment many Cubans had been waiting for, eager to hear his remarkable lectures and his interweaving of questions that invited reflection and action with judgment, compassion and responsibility in the face of vital dilemmas.

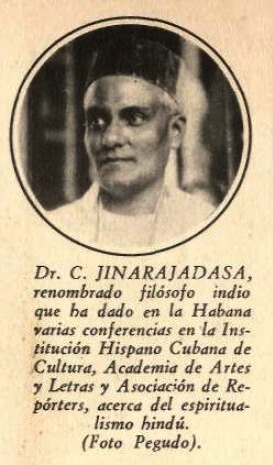

Who was Jinarajadasa?

With a name like a tongue twister, Curuppumullage Jinarajadasa was a man whose destiny revolved around the alchemy of ideas and the mysteries of modernity. He was born in December 1875 in British Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka), the island that resembles a teardrop at the foot of India.

His first contact with the world of Theosophy occurred at the age of thirteen, when he met the great mystic and seer C. W. Leadbeater. Leadbeater took over his mentorship and was influential in bringing the boy to England. Barely a year later, Jinarajadasa had his first taste of discipleship when he swam at night to the ship that would take him to London. He was leaving behind his homeland and his Buddhist family, feeling — he claimed — called by wisdom and duty.

With clairvoyant talents, from a very young age he displayed a voracious curiosity to understand the laws of the universe and attain the truth of things. Along this path of constant, yet unhurried, search, the doctrines of Tagore and Madame Blavatsky served as his compass. In the classrooms of his mind, he sought to balance science and belief, while the channels of his interest ran between religion, philosophy, literature, art, science, chemistry, Freemasonry and spiritualism; until his own work began to project itself on the border of the tangible and the occult.

He earned degrees in Oriental Languages and Law from Cambridge University. That student period was a trance for him — he compared it to climbing a mountain in agony and inner crucifixion without anyone noticing — due to the gap between his esoteric training and the vision of British university students.

Back in Sri Lanka, he served for two years as vice-principal at Ananda College in Colombo, founded by his teacher, and was charged with guiding the child Krishnamurti, the one with a perfect and pure aura — according to Leadbeater — whom they intended to educate to become a new Buddha. But Jinarajadasa abandoned the position, driven to despair by the boy’s rebelliousness, who refused to submit to any form of discipline.

At the beginning of the 20th century, he decided to pursue further studies in Italy. Despite the difficulties imposed by World War I, in 1914 he began a worldwide tour in a prolific career as a theosophical lecturer and writer that spanned almost 40 years and resulted in 50 books and 1,600 articles. “He loved children, the sea, Beethoven, Wagner’s Ring, the Hallelujah choruses and his Gospel was Ruskin,” reads the epitaph he himself wrote, a vivid glimpse into his soul, shortly before his death in 1953 in Chicago, United States.

Jinarajadasa was not the typical sedentary thinker in an academy or an Indian palace, meditating in the position of a monk with his gaze lost in the infinite. His main object of study was the world around him and he often traveled around it incessantly. In practical terms, this allowed him to compare and analyze different societies and, with the maxim that truth is discovered through action, he sowed the seeds of his spiritual movement in each place.

His method was simple yet rigorous: he observed without judging, he questioned without imposing. He believed that answers emerge when the “I” (the individual) dissolves into the “we” (the collective) and when the mind draws on multiple traditions, cultures and times.

From the perspective typical of Theosophy, he spoke of being, time and the way the world often twists when confronted with a new idea. He also spoke of patience, the beauty of the sinuous and the need to listen to the tension between two poles to understand the hidden truth. He also spoke of esoteric experiences; of dreams and states of consciousness that allow us to glimpse patterns, karmic relationships and déjà vu; of contemplations of the soul.

He developed guided techniques and self-help systems. He dreamed of a more humane and peaceful world, where science would dialogue with intuition and the spiritual would not be buried by dogma. He knew how to answer all kinds of questions, even those that others preferred to avoid because they were uncomfortable. He seemed to open paths where others saw walls, and that’s why he soon became a bridge: not only between eras and wisdom, but also between cultures.

His lectures

As soon as he arrived in Havana, Jinarajadasa asked to be taken to Parque Central to lay a wreath bearing the insignia of the Theosophical Society before the statue of the Apostle Martí. The same afternoon of his arrival, he was received in a private audience by President Machado, with whom he at length discussed educational matters and the granting of suffrage to women. He then met with General Alemán, Secretary of Public Instruction, and the municipal mayor.

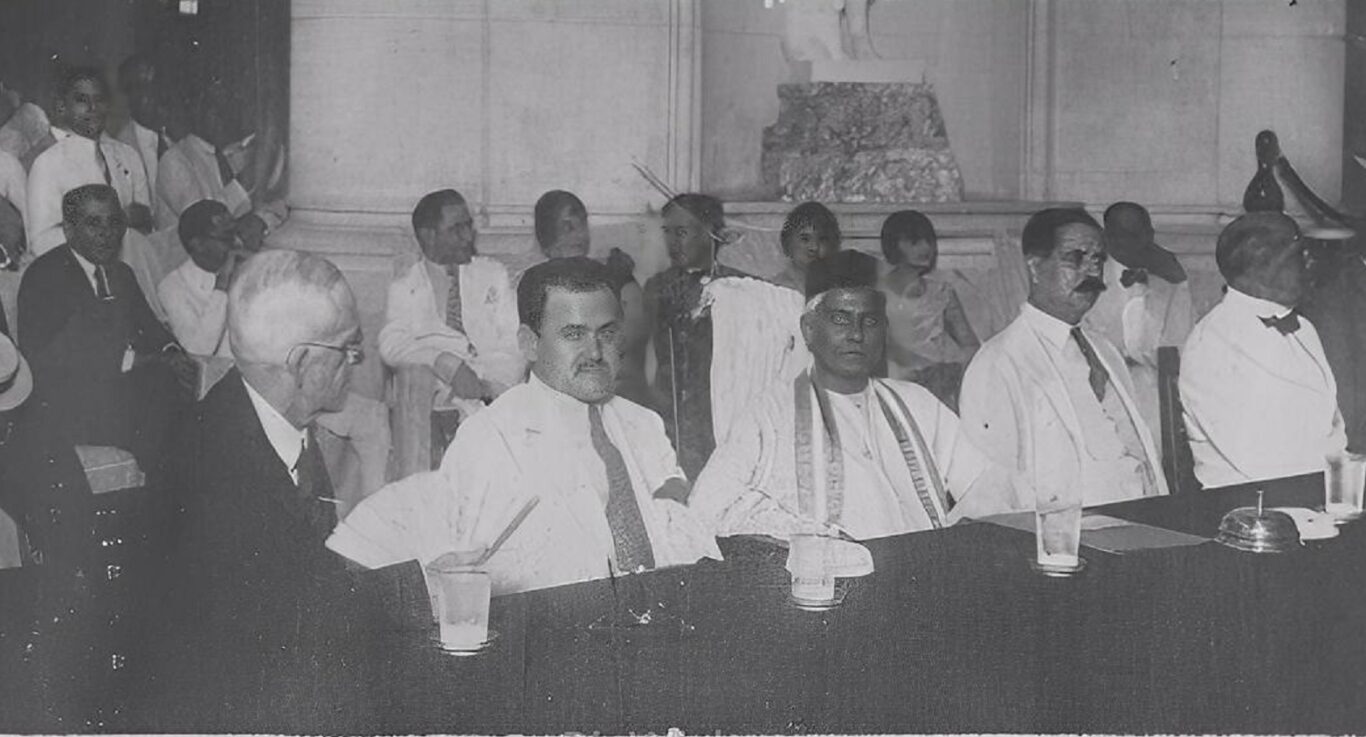

He barely had time to take his trunks to the residence of Dr. Dámaso Pasalodos in Jesús del Monte, where he would stay for the eight days he spent in Havana, and to change his clothes. Now dressed in his white robes, gold-fringed stole and the biblical sandals of a venerable prophet, he regained his appearance as a man obsessed with the word of God and the idea of the purification of humanity.

Punctually, at five o’clock on Thursday, September 5th, and showing no signs of exhaustion after the boat trip, the Hindu scholar was at the Reporters Association ready to deliver “Hindu Civilization,” the first of his series of lectures at Havana institutions. In it, he summarized the history of India and the industrial leap it had taken. He also noted that each individual occupies a place in society that must be exploited through personal work, as this liberates and leads to a state of superiority.

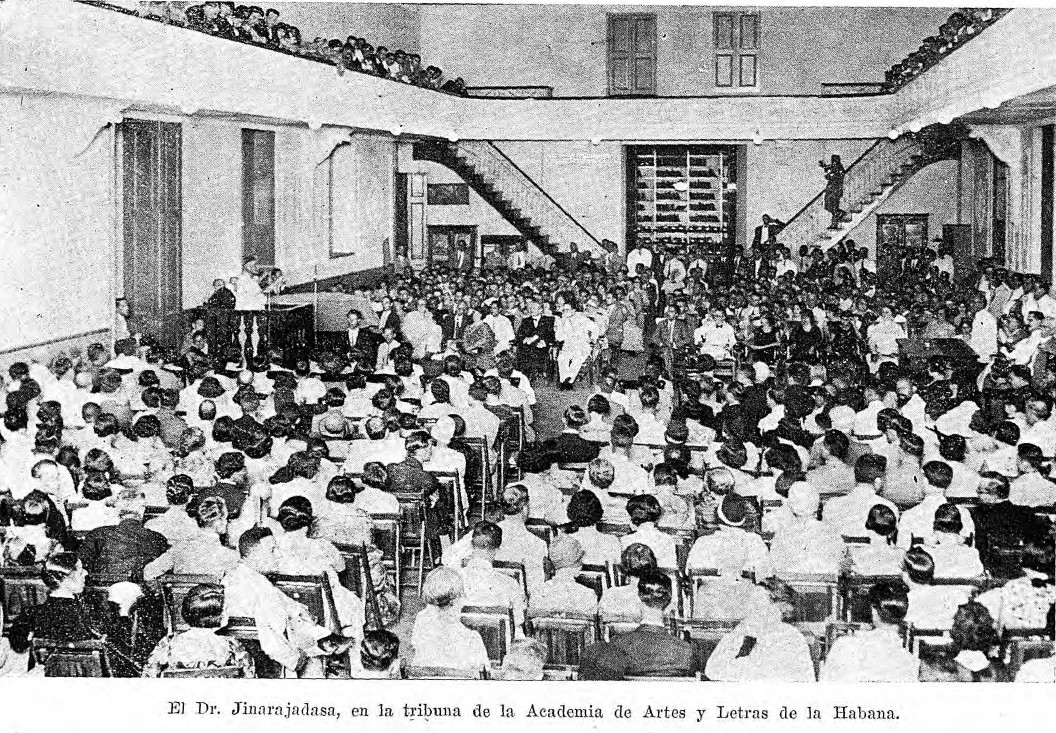

That evening, he went to the Academy of Arts and Letters to offer his “New Theories on Education.” In short, he discussed teaching and, among other ideas, criticized: “Education in the West is not universal; it is exclusively aimed at placing in the hands of certain men special weapons of war that will enable them to win more easily. The ‘feeling of war,’ in all its nuances, is what is taught. It is an education exclusively for the brain, neglecting emotion.”

During the following days, he gave lectures on “Gods in Chains” (which would later become one of his best-known books), “Businessmen,” “The Idealism of Theosophy,” “The Teachings of Krishnamurti,” “The Perfect City of God and Man,” and, to close the series, “True and False Yoga,” sponsored by the Spanish-Cuban Association at the Martí Theater. The titles reveal the diversity and depth of the topics.

His lectures aroused such interest that, to the delight of his listeners, the C.M.C. Radio Station broadcast all four lectures, which took place at the Academy of Arts and Letters. He also spoke for half an hour at the Rotary Club and at the Union Club, where, in the ecstasy of a tea party held in his honor, the philosopher uttered one of his enigmatic pronouncements: “Where do I come from, who am I, where am I going? Wealth and health do not imply happiness. On the contrary, poor men consider themselves happy. Happiness lies in spiritual contentment.”

“An interesting event,” commented columnist Enrique Fontanills. The detailed coverage of these presentations by Diario de la Marina, Carteles and the Revista Teosófica Cubana allows us to revisit this story today.

His name in the press

“Approaching Jinarajadasa is like looking through an open window onto an infinity sensed in our dreams, or like remembering vaguely forgotten things, perhaps remnants of our lives. His words acquire silken softness, unexpected resonances of undertows on golden sandy beaches. Suddenly we forget that we are speaking with a son of ancient India and we seem to see him in the marble-lined agora under the sun of Hellas, offering his disciples, in slow walks, the Attic honey of his wisdom.” Thus, with the grace of her pen and the good fortune of having been able to analyze him with her own eyes, journalist Mercedes Borrero introduced the readers of Carteles to the interviewee she called “Escultor de almas” (Sculptor of Souls).

In the interview — published full-page by the magazine on September 15 — the philosopher thanked the Cuban people for the kindnesses shown him since his arrival, shared impressions of his travels in the Americas where, he asserted, “the cultural level of women is superior to that of men,” and added that, as long as women were not granted the rights to which they are entitled in the work of social collaboration, “the ideal of a new human morality cannot be realized.”

Regarding the problem of Palestine, he opined that “it cannot be resolved because neither Arabs nor Jews are prepared for self-government,” expressed messages from the Hindu gospel and expressed his forward-thinking vision of child pedagogy. “I maintain that the child has a soul, something sacred, uniquely his, inviolable, and that the teacher’s duty is to give the child every opportunity to manifest that soul, without requiring any discipline between teacher and student other than that of love. In this way, the child will be the sculptor of his own personality.”

The magazine Revista Teosófica Cubana was not short on praise, describing him in its September 1929 issue as “a true philosopher and a remarkable scientist, as well as a great pedagogue who cultivates not only the mind but also the spirit, and who has been forging new paths in educational matters. He has earned the highest distinctions from educators, government officials and intellectuals in all the cities he has visited.”

In October, the magazine launched an interesting survey for its readers: “Now, what has remained with us from Mr. Jinarajadasa’s visit…? Was it a fleeting emotion, a spasmodic enthusiasm that lasted only as long as we saw him, or something lasting that can serve us after his departure…? Has he been able to change our concept of life and things? Has he served to inspire us to live more loftily and nobly?”

Although the Diario de la Marina compiled a log recording every activity of the theosophist, in its September 9 issue it did not mince words when it published a text by the Reverend H. Chaurrondo that attributed vulgar slips of the tongue to him: “But two transcendental points of his lecture did not fit within the ideology of his listeners: they are the doctrines that fundamentally separate the East and the West: his pantheistic concept of the world and the denial of the individuality of the human soul. The Hindu master, in trying to explain this separation and at the same time union of the soul of the world and of God, assuring that the human soul is identical to that of God and is distinct, two in one and one in God, cast a chill over the audience when he said: ‘Don’t ask me, because an ancient Indian hymn already says that not even God himself knows.’ A charming explanation for these times and for these people!” The following day, Jinarajadasa forwarded his denial to the newspaper.

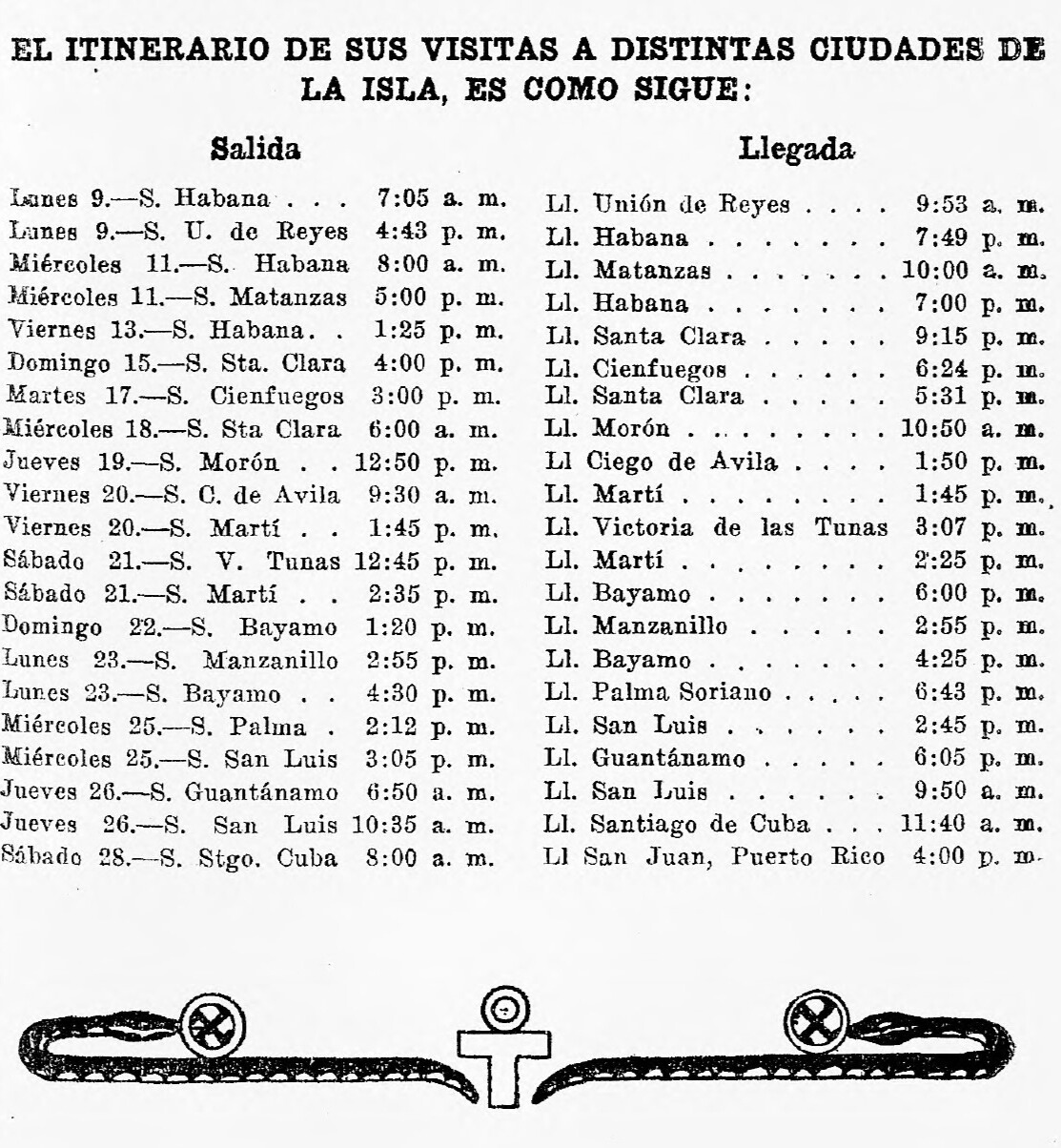

To Santiago by train

Having completed his Havana agenda, the Hindu scholar began his theosophical outreach tour of the provinces. He basically gave the same lectures he had previously given in the capital. From the sources at my disposal, I don’t have complete details of his activities in the interior of the island, but I can say — judging from the published photos — that he filled the Terry Theater in Cienfuegos and was received by the mayor in Santa Clara. In two days, he made excursions to Unión de Reyes, Alacranes and Matanzas, where he gave brilliant presentations.

On his way to the eastern region, he stopped in several cities and towns. The trip included vegetarian meals, talks with children, exchanges with women who championed women’s advancement and meetings with Rotarians.

On the morning of September 26, 1929, Jinarajadasa was received at the Santiago de Cuba train station, where he stayed at the home of Dr. César Cruz Bustillo. That evening, he gave his first lecture in the halls of the Vista Alegre Club. His second lecture took place at a Rotarian luncheon at the Casagranda Hotel, where he attended “dressed in the traditional costume of his country” and aroused admiration among those present by presenting “The Idealism of Theosophy.”

He also had the opportunity to appear “before an intelligent, cultured and understanding audience,” giving two more lectures with his enchanting musical Spanish: one at the Vista Alegre Theater and another at the headquarters of the Luz de Oriente Society. He then traveled by air to Santo Domingo and Puerto Rico. He returned to Santiago two weeks later to participate in the Annual Convention of the Theosophical Society. On October 15, he took another plane to Havana to give his farewell lecture that evening at the Asturian Center, this time entitled “Let’s Disarm the War.” The following day, he departed on the Oroya steamer for Spain, bound for India.

Jinarajadasa liked the atmosphere of Cuba and its people. Here, he found a thread of spirituality, a yearning for knowledge and hearts open to discovering the truth: the truth that is not found in temples, nor in the speeches of priests or rulers who subject it to subjectivity and human error; the truth that underlies and manifests itself in many forms: the harsh truth of life.