Until March, Julio Álvarez had a dozen cars in motion, classic Chevrolet and Ford from before the 1959 revolution in which tourists toured the Havana Malecón for 30 dollars an hour and took pictures. Now the cars are parked in his garage, the visitors have disappeared, and his drivers remain at home.

Until the arrival of the new coronavirus, there were some 600,000 entrepreneurs in Cuba―a record number since former President Raúl Castro approved limited economic reforms in 2010― of whom at least 139,000 temporarily turned in their licenses and thousands of others closed due to the measures taken by the authorities.

“We are in an impasse,” said Alvarez, co-owner of Nostalgicar, a family business that emerged nine years ago. “We had 16 contracted workers. I can’t keep them. They earned their money and are living off their savings.”

Like many, Álvarez is concerned about the situation of the island’s vulnerable private sector, where small and medium enterprises still don’t have legal status and entrepreneurs made their way with difficulty after six decades of a centralized state model.

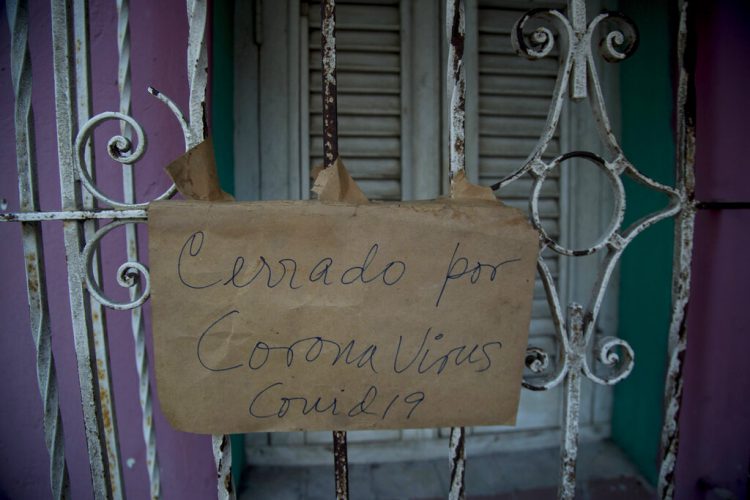

These days it is common to see the “Closed” sign in cafes, bars, restaurants or home rentals and the private taxis―the classic ones like those of Álvarez for tourists or the less showy for the population―are at a standstill.

The first three cases of COVID-19 were confirmed on March 11. On the 24th, the authorities suspended classes, closed airports, confined foreigners stranded on the island in their hotels, suspended car rentals and all recreational activities.

With this, the license of some 50,000 taxi owners ceased until further notice, at the same time as the urban and interprovincial state buses stopped running.

All this came at a time when there was a strengthening of U.S. sanctions that seek to suffocate the Cuban economy to press for a regime change plus the internal obstacles themselves.

“The private sector, especially the most attractive businesses…were already suffering a contraction from the strengthening of the (U.S.) blockade policy against Cuba that included the closing of cruises…. Afterwards came the cancellation of flights to the provinces, the limitation of the people who came,” economist Omar Everleny Pérez explained to the AP.

Tourism, followed by professional services, constitutes one of the main sources of income for the island. The sector leaves some three billion dollars a year to the State and a similar amount to individuals who rent houses, prepare meals or organize guided visits.

The relationship between the government and the island’s entrepreneurs has been zigzagging.

In 2010 Raúl Castro acknowledged that in the face of an oversized state payroll and the lack of productivity, opening to the self-employed, as entrepreneurs in Cuba are called, was necessary.

The government gave thousands of hectares of idle land to individuals and authorized the sale and purchase of real estate and bank credits, but maintained a strict list of a hundred authorized activities; it did not allow the opening of firms to professionals such as engineers, architects or lawyers, nor did it open wholesale markets, among others.

Although 70% of Cubans work for the state, more than half a million people embarked on different ventures: from street vendors and seamstresses to luxury hostels and restaurants where a dish costs 20 dollars, half a state salary.

Those who engaged in independent work substantially improved their income. Álvarez’s young mechanics, for example, have contracts for a minimum of 2,000 Cuban pesos a month (80 dollars), much more than they would get at a state workshop.

The pandemic―which has left more 1,400 infected and more than 50 dead to date on the island―found Cuba with a growth in Gross Domestic Product of just 0.5% in 2019, a population subjected to long lines to buy food due to the lack of liquidity in the country to pay its external suppliers and shortages of fuel and supplies for medicines.

Last week the Economic Commission for Latin America (ECLAC) estimated a 3.7% drop in the Cuban economy this year, while experts such as Everleny Pérez estimate that it could reach 5%.

But the economic impact will not be the same for everyone.

“It’s not the same for a business owner who was able to accumulate certain contingency reserves as for a hired worker who depended on his almost daily income. That is, a very bleak picture,” explained the economist.

The contraction in remittances will also hit the island as many of the entrepreneurs’ investments are supported by funds sent to them by their relatives who live abroad and businesses obtain income from the small internal market that is fed by this flow.

Economist Emilio Morales, of the Miami-based Havana Consulting Group, estimated at 3.6 billion dollars the cash sent by Cubans to the island in 2018, to which another 3 billion are added if the goods that the emigrants bring are considered.

Marta Deus: “These are times to work hard and reinvent oneself”

The few Cuban entrepreneurs who did not turn in their licenses are trying to re-adapt. Restaurant owners have started making home deliveries, beauty salons set up consultancies on social networks and clothing stores sell through Internet pages.

Álvarez is thinking of adapting the workshop to restore third-party cars and hostel owners are evaluating targeting national tourism.

The government promised tax cuts, but it is unknown whether there will be a systematic and coherent policy to stimulate the fledgling private sector.

However, several entrepreneurs and experts consulted by the AP hope to get something good out of the coronavirus crisis: a deepening of economic reforms that, without losing the socialist sense, will allow them to consolidate, gain legal recognition and expand the areas of authorized activities.

“I’m optimistic,” Gregory Biniowsky, a Cuban-based Canadian consultant and co-founder of the Nazdarovie restaurant, which is now closed, told the AP. “Although we are going to recover slowly.”

Biniowsky added that “this crisis may shake the State a little and will make decision makers be more open to changes within Cuba that support entrepreneurs, such as allowing us to import inputs at wholesale prices. They can’t afford the collapse of the non-state sector.”