Minimized and loved, followed by millions and vilified by those who prefer to contemplate the world from an ivory tower, radio is celebrating 96 years since of its first regular broadcasts in Cuba.

It’s easy to say, but it is not so.

This Caribbean island was one of the first countries of the American continent to have stable radio stations – a term actually grandiose for its artisan beginnings -, established even in the midst of shortages and improvisations, of its own obstacles and the astonishment of an audience that had never known the likes of it.

The foundational ranks are owed to military musician Luis Casas Romero, who was the subdirector of the Band of the General Staff of the Army and who on August 22, 1922 inaugurated the 2LC, but the birth of this means was not a thing of one day, as neither was its consolidation.

Cuban radio was created step by step, test after test, mistake after mistake. It was actually the result of the simultaneous effort, the search and the creativity of a tireless group of radio hams, not just in Havana but throughout the island, and also of the skillful businessmen who rapidly understood the possibilities of the new invention to line their pockets.

Without them everything else wouldn’t have existed.

To get to the powerful CMQ of the Mestre brothers, the radio enterprise that dominated Cuba and got the audience eating out of its hands with the first broadcast of “El derecho de nacer,” the 2LC’s honks and its first weather forecasts were necessary.

https://oncubamagazine.com/sociedad/el-derecho-de-nacer-y-llorar-con-caignet/

For a station at the other tip of Cuba, in Santiago, to emerge and try to conquer the island from east to west and to present live international stars like Libertad Lamarque, the notes from a phonograph had to cut through the atmosphere, transmitted from its basement by the CMKA.

Yes, from a basement…

Arturo C. de Ribas was one of the pioneers of Santiago de Cuba’s radio broadcasts, the person responsible for the first regular broadcasts in Cuba’s second city. Already by then, February 1930, the radio was not exactly a novelty and in Santiago several attempts had existed to consolidate a station, although with no luck.

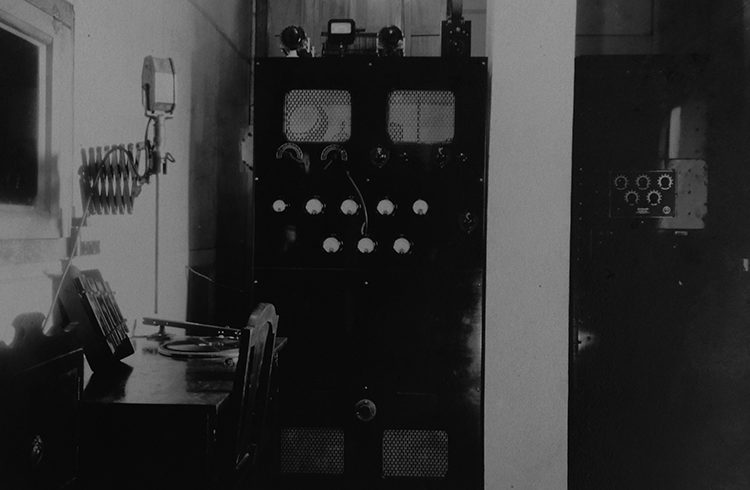

Arturo had tried to do it himself several times, until finally he achieved it from 1ra Street on the corner of 8, in the Vista Alegre district. The plant operated on the 204-meter wave length and was in his home. In the basement, to be more precise.

Its owner, who was also its first broadcaster, had no complexes when presenting it: “This is CMKA, broadcasting from my home’s basement.”

The local press did not overlook its emergence and even before it came on the air it prepared the ground among the potential listeners. The first day’s billboard was presented like a program of the Radio Sales Corporation, an agent in the former province of Oriente of the Philips Centro América S.A. company, which discerns the link of the nascent station with the entrepreneurs.

Its programming was purely musical, with Cuban and Mexican songs, sons, foxtrots and opera, among other genres.

plaque about the first regular radio broadcast in Santiago de Cuba on the side wall of the

current building, the venue of a childcare center.

Little by little, with the effort and backing of partners, friends and relatives, De Ribas was able to maintain two hours of daily broadcast, between 5:30 and 7:30 p.m., a prime time in which together with the recorded music – thanks to a microphone and the trumpet of a phonograph – local artists like soprano Dulce María Hernández, violinist Electo Rossell, “Chepín,” and pianist Bernardo Chauven, “Chovén,” sang and played.

The Diario de Cuba, one of the leading publications in eastern Cuba, would not take long in being linked to the new means with the inclusion of “talks sprinkled with news dispatches and local news.”

But the CMKA’s leader wanted more, and he soon dared to come out of the Vista Alegre basement to broadcast sports events, lectures and concerts.

One of the small plant’s hallmarks took place in March 1930, a short while after it came on the air. That day, the CMKA moved its equipment to the centric Céspedes park to broadcast a public show: the open-air concert by the Band of the Municipal Police.

For this, De Ribas and his collaborators had to assemble a 150-watt transmitter close to the park, a heavy equipment which they had to move from the station’s locale. But they weren’t daunted and after the broadcast they received letters with reports that it had been heard from places very far from the city.

The CMKA did not have a long life. Despite its team’s will and its innovations it ended up ceding the leading role and it disappeared. Other Santiago stations like the CMKC – still active more than eight decades later – and the CMKD, with better economic and artistic conditions, followed its steps and also left their imprint on Cuban radio broadcasting.

But what was done by Arturo C. de Ribas is a sign of the immense value of what apparently is small, of what is frequently forgotten or unknown. Even in such a populated universe as the history of radio. Even from a basement.