Four years ago, economist Juan Triana wondered what was happening with the “national mammal,” whose meat had become elusive to the majority of the Cuban population. “Four years ago,” Minister of Agriculture Idael Pérez recently said, “we had about 96,000 pig breeders…. Today we have 26,000, not in good condition.”

Four years ago, the delivery of pork to the national balance sheet seemed to hit rock bottom, when at the end of 2020 only 93,400 tons of pork were delivered to the industry, according to the Statistical Yearbook of the National Statistics and Information Office (ONEI). But the worst was yet to come: in four years, production in this sector decreased even further (more than 85); in 2023, the lowest figure in the last 15 years was recorded: 13,300 tons.

With this “thunder” the price storm was perfect. If in 2020 the economist Triana referred to prices between 40 and 50 pesos per pound — and in that pre-Reorganization context it was already unaffordable for many — the most recent publication on Minimum and Maximum Prices of Varieties (August 2024), by the ONEI, places it between 600 and 700 pesos per pound in most of the country’s provinces, and up to 850 in Havana.

Taking into account that the minimum pension is 1,528 pesos, it is easy to estimate that a not inconsiderable part of the population has not been able to afford a pork steak for some time.

What happened?

Judging by the few explanations given by the Minister of Agriculture at the Mesa Redonda TV program in early October, the collapse of pig farming in Cuba can be attributed to the tightening of the blockade and the international economic crisis, which have had an impact on the increased process for raw materials, the cost of maritime transportation and the lack of fuel.

But the imbalances precede this combination of factors. The feature article “Puercos jíbaros,” published in the newspaper Invasor, of Ciego de Ávila, at the end of 2018, showed the contradictions that the sector was dragging along and that, in view of the new year and the announcement of the obligation to pay personal income tax for pig breeders — for the first time since Law 113 of the Tax System was approved in 2012 — predicted the crisis.

The pig farmers in the province said that without feed — by then the breach of the agreement with the Porcine Enterprise was already being accused — and with “the tax authorities’ confusion and disorder,” the mass was going to decrease, because it was unsustainable. “I had 1,000 and now I decided to stay with 400; and like me, a lot of people are reducing their contracts,” said a breeder with more than fifteen years of experience.

The feature also pointed out that the feed deficit was not new. At least four years earlier, the same local media had investigated the issue: if in 2014 the debt was about 4,000 tons, in 2018 it had almost doubled. The Porcine Enterprise was not fulfilling its part of the agreement and it was not easier for the farmers to guarantee 30% of the feed as established in the contract.

The then president of the National Association of Small Farmers (ANAP) in Ciego de Ávila recognized: “the instability in fuel has been constant. Those who have to plant hectares of feed need fuel and what has happened is that their allocation has been reduced.”

Between feed and taxes, pig farmers began to struggle with “paperwork.” Pig farming is highly polluting due to its waste and, although late, the Ministry of Agriculture (MINAG) began to demand requirements. This led to the forced closure of some pigpens and the termination of contracts due to non-compliance with environmental and health requirements, in addition to the decision of the Credit and Commerce Bank not to approve loans to those who had not resolved their “illegalities.”

In the midst of all this, the plans remained immovable, only to end up not being fulfilled.

Chicken are coming home to roost

The Ciego de Ávila debacle was repeated in Villa Clara and Sancti Spíritus; the three provinces constituted the country’s pig stronghold, with the largest producers and the largest deliveries to the national balance sheet. Based on the historical results of the last five years, this area was projected to produce around 200,000 tons in 2018: a national production record.

But that year was also unfortunate in both provinces: in Villa Clara, in addition to the deficit of feed for fattening (a debt of about 10,700 tons), Hurricane Irma (September 2017) impacted the breeding sows, taking away 80% of the basic mass — “around 400 sows and more than 1,000 offspring were lost,” explained the newspaper Vanguardia.

In Sancti Spíritus, also affected by the intense hurricane, other causes reduced the totals: “health problems in our units last year forced us to sacrifice 760 breeding sows. For these two reasons we stopped having about 14,000 pigs that represent 1,400 tons of meat in the plan; another reason is the feed debt with the agreements,” confirmed to Escambray the general director of the Porcine Enterprise of Sancti Spíritus, José Antonio Piña.

According to Piña, the announcement of the payment of the tax as part of the Budget Law approved by the National Assembly caused more than 40% of producers with their own animals to withdraw from fattening.

Even so, in 2018, 149,400 tons of pork were produced in batches — according to the Statistical Yearbook. Manufacturing Industry. 2019 Edition. It was the highest figure in the last 15 years, but at the same time it would mark the beginning of the sustained and unstoppable decline of the sector, with devastating impacts on the national diet.

Pork, the most popular and affordable meat for the Cuban population, disappeared from the markets or became inaccessible. Even today it has not found its way back to people’s tables.

Its price, as we pointed out, has moved into the stratosphere and good intentions and sales control actions are not enough to lower it. The problem is in the pens.

Reversing the matrix?: pork rinds are not meat

Intensive pig farming depends on an abundant and specific diet: for an animal to reach 90 kilograms in 6 months, it needs feed based on cereals, proteins such as soy, and amino acids. The conversion rate ranges between 3.5 and 4.0 kilograms of feed per kilogram of meat.

Since 2018, the agreement between state-owned enterprises and individual producers, through which the State supplied 70% of animal feed, did not guarantee production cycles.

In another Mesa Redonda (May 2020), the then Minister of Agriculture, Gustavo Rodríguez, said that there were no conditions to maintain this type of contract — already at that time the feed debt reached 90,000 tons. “In the coming years we have to reverse this matrix, gradually.” Reversing the matrix would put us where we are now.

The second immediate impact, after the “disappearance” of meat, was the decrease in producers: from 14,000 active in 2018, there were barely 6,000 in 2020 and the number would continue to decrease.

Two years later, during the national plenary meeting convened by the top leadership and the Ministry of Agriculture to discuss with the breeders “how to recover and increase the supply of the most preferred protein in the Cuban diet,” the decision not to import feed and the need for each producer to guarantee animal feed was repeated.

In the midst of the debate, even the pig farmers with the best results, based on allocating hectares to sow cassava and corn for pigs, made it clear that it was not enough. The pig farmer from Pinar del Río Reynier de Jesús — who had come to have pigpens with 3,000 heads and at that time only had half of that — explained that 40 hectares of sown land do not fatten 1,500 pigs.

With this certainty and to exploit the niche of an undersupplied market, the joint venture Bioamazonas Pienso S.A. was born in February 2024, an economic alliance between the Cuban entity Ganadería S.A. — belonging to the MINAG Livestock Group — and the Brazilian company Bioamazonas S.A.

Located in Industrial Zone No. 2 of Obourke, Cienfuegos, the production plant must deliver 50 tons of feed per hour. “A simple producer or housewife who loves agriculture and animal care can come to the institution and purchase from a sack to a ton of the merchandise, using the prepaid card of Bandec and Fincimex, which can be purchased at Cadeca exchange offices and at banks. All through digital operations,” said the Cienfuegos radio station in May, during a visit to the enclave by Cuban Vice President Salvador Valdés Mesa.

The operation is not exactly simple. Payments are made in foreign currency, using the new dollar debit cards. According to the newspaper 5 de septiembre, “prices range between 25 and 30 dollars — it does not specify the cost per unit of measurement, we assume one kilogram —, depending on the type of product ordered.” That is, the State cannot import feed for fattening, but producers are forced to pay for it in foreign currency if they want to continue raising pigs.

This is what the medium-sized private enterprise Carnes D’Tres, based in Ciego de Ávila, has had to do. It currently imports feed and in 2022 it seemed to be the first of its kind to participate in an International Economic Association, through foreign direct investment; but there has been no further news of this.

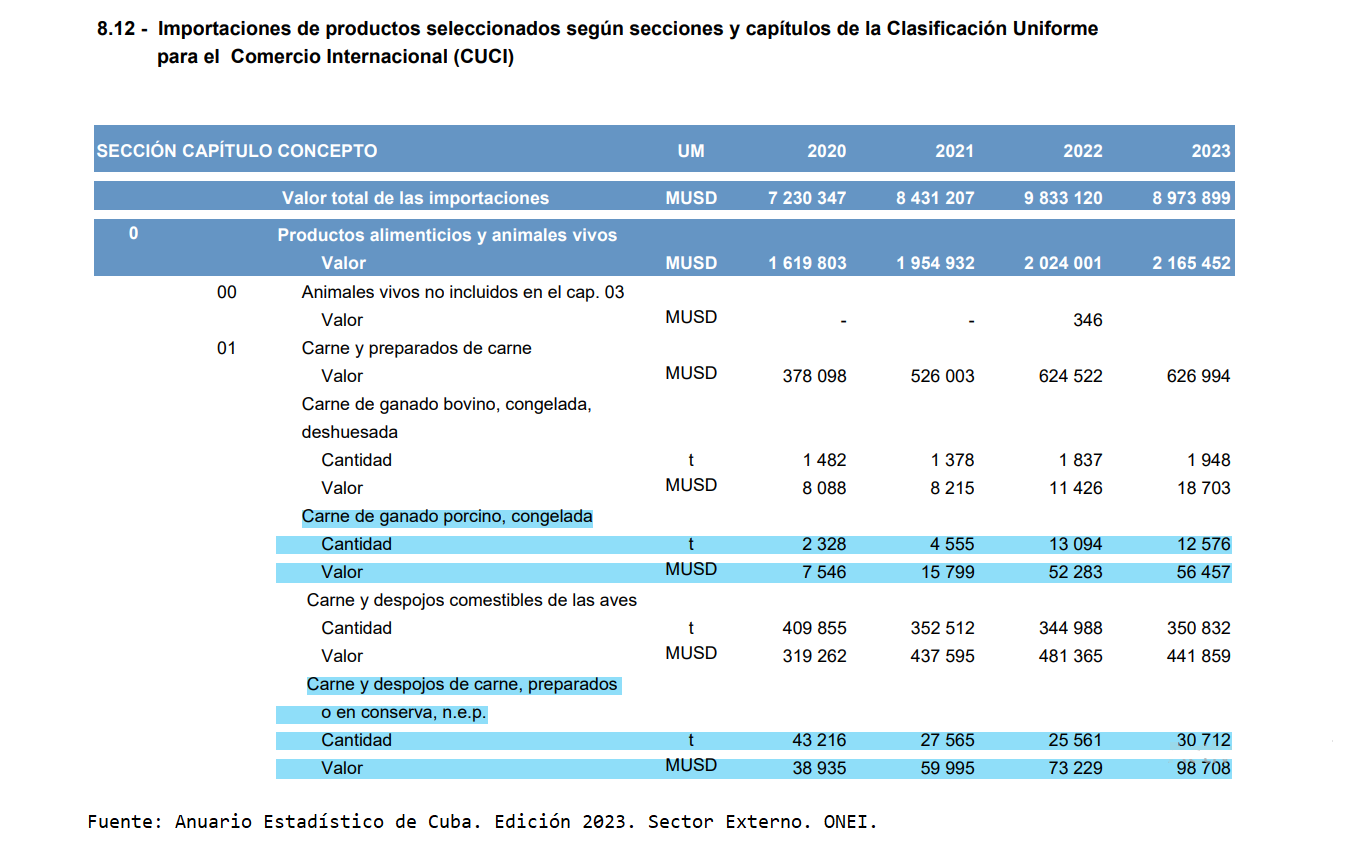

While the production of pork in batches fell to levels never seen before (15,000 tons in 2022 and 13,000 in 2023), since 2019 the import of frozen pork has increased (36,747 tons in the last five years, worth 145,370 dollars), according to the Statistical Yearbook. Edition 2022, External Sector. Apparently, the “matrix” ended up reversing on one side only.

The price of the little meat that reaches the counters remains in the “headlines” of each day of the vox populi and, although a speculation component is not ruled out (increases by intermediaries), the ways in which these animals are fattened today ― whether with national or imported feed ― added to the taxes applied (in the case of MSMEs it is 11% for sales) do not leave room for decline.

Four years ago, Dr. Juan Triana concluded his analysis by calling for improved incentives, updated regulations, and smoother paths. Everything remains to be done.