In the Floridita you can have 17 types of daiquiris: coconut, strawberry, mint, kiwi, mango…are among the options for visitors to the most famous of Havana’s bars.

Its bartenders even offer a non-alcoholic variant so the teetotalers and children can also leave the place pleased.

“With no chauvinism, the best daiquiri in the world is made in the Floridita,” affirms Ariel Blanco, director of the bar-restaurant that currently belongs to the state-run Palmares chain.

Located in the intersection of Obispo and Monserrate streets, in Old Havana, the establishment is celebrating this year two centuries of existence. Its fame, mainly associated to the figure of writer Ernest Hemingway and the excellence of its daiquiri, has turned it into an obliged site for tourists worldwide.

More than a quarter of a million visitors arrive every year to the Floridita. Its director estimates that around 80 percent of the Americans who travel to Havana can’t resist the temptation of entering the bar.

However, there are not many Cuban clients. Many on the island can’t afford the bar’s prices – around six dollars for the classic daiquiri.

But the numbers, neither of Cubans nor of foreigners, say it all.

To understand the meaning of this place one has to discover its history and confirm, cocktail in hand, the vitality of an inheritance sustained throughout time.

“Our principal challenge is to renovate ourselves,” affirms Blanco, “but maintaining the roots of our tradition.”

FROM LA PIÑA DE PLATA TO THE FLORIDITA

It was in July 1817 when the locale opened its doors. At the time it was named La Piña de Plata, although some time later it would change its name to La Florida.

According to journalist Ciro Bianchi, La Piña… was “a mansion with barred windows, which received dandies, musicians, military, socialites and all kinds of men wanting to taste the delicious compound gin, the glass of water with anise and honeycombs, the typical ‘voluntary’ vermouth, the pineapple liqueur of the delicious morello cherry spirits, while the ladies, in their buggies, under their silk parasols, savored fruit sweets, sherbets and glasses of refreshments made from the country’s fruits.”

Later, during the U.S. military intervention of the island, the place became “the general headquarters of the good U.S. tasters,” while “bartenders started adding a bit of modernity to the simple primitive drinks.”

Ciro sets the change of name after the instauration of the Republic. However, as La Florida it would not last much. The existence of another famous bar in the Florida Hotel, founded in the late 19th century, made drinkers seek a way to distinguish them. They then started calling Floridita the one on the corner of Obispo and Monserrat, and the name ended up being imposed.

In 1910 the establishment was expanded to make room for the restaurant, which in the beginning was led by a French chef. Little by little, the site started having the physiognomy it has today.

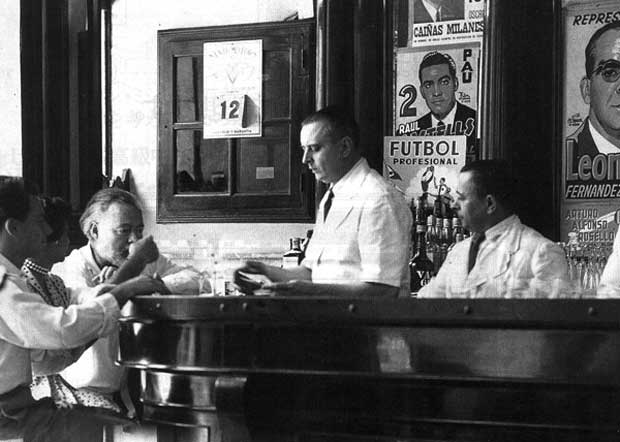

A key moment in the history of the Floridita was the arrival of the Catalonian Constantino Ribalaigua Vert. Constante, as he was known among his acquaintances and clients, started off as a bartender at the bar in 1914 and a few years later he was already the owner.

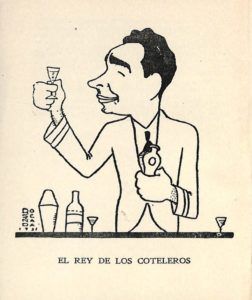

Because of his skill and creativity, Ribalaigua was known as “the king of cocktail makers.” Such famous mixtures as the Presidente – created for Cuban President Mario García Menocal -, the Mary Pickford – in tribute to the silent film star – and the Havana Special, the name of the shipping line that made trips to Cuba from Key West, were born from his ingenuity.

The daiquiri was not one of his inventions – it had emerged, in a primitive version, at the beach by the same name in Santiago de Cuba – but he knew how to take the cocktail to a higher level. To its initial ingredients – rum, sugar and lime juice – he contributed their exact measures and added to it maraschino and shaved ice, which had to be dried to give it the desired consistency and to avoid its being liquefied in the bottom of the cup. This magic touch, says Ciro Bianchi, “gave it its international naturalization papers.”

The anecdote of U.S. journalist Jack Cuddy, who on a visit to Cuba wanted to get to know the island’s best barman, is well-known. “It’s Constantino Ribalaigua,” he was told. To confirm it, Cuddy and his companions phoned Havana’s principal bars: Sloppy Joe’s, the Plaza and Sevilla hotels, and Prado 86. All the opinions favored the Catalonian.

The journalist then wanted to meet him personally. His visit to the Floridita left him with no doubts. Cuddy wrote that after Constantino had him taste several of his creations he had to admit to himself their undeniable superiority. He didn’t know how much he charged but he believed he had the right to ask for a raise before signing the contract for the next season.

Constante perfected the seducing power of his mixtures up to his death in 1952. After he died Hemingway would write: “The maestro of bartenders has died. He invented the Floridita….”

One year later, the U.S. magazine Esquire included the place among the seven most famous bars worldwide. It was a posthumous tribute to the greatness of Ribalaigua.

HEMINGWAY AND THE DOUBLE PAPA

Ernest Hemingway was famous for his novels and newspaper articles. Also for his love of hunting and fishing, for being an inveterate womanizer and his search for German submarines during World War II. But, with these and other reasons, one cannot forget his love of drinking,

“In the Floridita we conserve many photos of Hemingway,” says the current director of the establishment, with a picaresque smile, “and in most of them the writer appears holding a drink.”

The author of The Old Man and the Sea outlined his own gastronomic route in Havana, guided by his passion for cocktails. And the Floridita, like the Bodeguita del Medio, became an indispensable place in his Havana tours. There were times in which it was like his office.

A phrase by him is an irrevocable testimony: “My mojito in La Bodeguita, my daiquiri in El Floridita.”

His literature does the same. In his novel Islands in the Stream, the protagonist, Thomas Hudson, returns once and again to the Floridita.

It is said that Hemingway entered the bar on Obispo and Monserrate by chance. He was looking for a bathroom. But once satisfied, his drinker’s curiosity led him to sit at the bar behind which Constantino Ribalaigua reigned. It was his first visit to Havana, in the 1920s, but the Catalonian’s mixtures definitively entrapped him.

Constante created the Double Papa for the novelist, a variation of his very famous daiquiri also known as the Hemingway Special. Compared to the classic cocktail, it does not take lime juice or sugar – a petition of the writer because of his condition as a fun-loving diabetic -, but rather grapefruit juice and a double white rum; also maraschino and the characteristic shaved ice.

The name came from the novelist’s nickname in Cuba: Papa.

The future Nobel Prizewinner liked to drink it during his assiduous visits to the bar, on the first stool to the left of the bar. Today many of the Floridita’s clients still ask for it to live a personal communion with Hemingway.

There where the novelist used to sit, visitors find today a bronze statue. It is a work by José Villa Soberón, the Santiago de Cuba sculptor who has perpetuated in Havana characters like John Lennon and the Caballero de París. Leaning on the bar, Hemingway gets mixed up as one more client.

Many tourists – as also happens with El Vedado’s Lennon and San Francisco de Asís Square’s Caballero – don’t leave the bar without taking a picture with the statue. It is already part of the ritual that feeds the legend of the Floridita.

A KING OF KINGS FOR 200 YEARS

During all of 2017 the Floridita has been remembering its anniversary. Two centuries, in short, are not celebrated every day.

However, the climax of the celebrations will be in the already nearby month of October. On the 5th and 6th the famous Havana bar-restaurant will host a sui generis tournament to choose the King of the Daiquiri; actually, the King of Kings.

The winners of the previous editions and some exceptional guest will participate in the event. There will be a total of 10 bartenders who will vie in a demanding contest which will require from those involved the greatest creativity.

“It will be a novel competition,” Ariel Blanco affirms, “that will have nothing to do with the previous editions. It will take place for two days: the 10 competitors will contest in the first and those chosen as finalists will get to the second. The champion will be decided among them.”

Eight Cubans, from the private as well as the state-run sector, will be seeking the crown, among them a woman, Dunia Rafa, who was the queen of the daiquiri in 2013. They will all face the challenge of beating Argentinian Cristian Dhelpech, 19-time world champion in the flair modality.

In addition, John Cristian Lemeyer, from the United States and the first bartender from his country to compete in the contest two years ago, who despite not having won was now invited as a symbol of the reestablishment of relations between Cuba and the United States.

“Our bartenders will not vie for the prize because they will form part of the event’s jury as the maestros of the daiquiri they are,” the director of the Floridita confirmed.

Among them Orlando Blanco, maître of the bar and the first Habano Sommelier world champion, stands out.

The participation of the executives of the International Bartenders Association (IBA) is expected in the King of Kings, as well as more than 200 bartenders and guests from the entire world, attracted by the magnetism of the Floridita.

The event, which will be sponsored by Havana Club International, will surpass the bar’s size and will be extended to nearby streets. Large-size screens will broadcast live the competition, to the pleasure of passers-by and neighbors.

“Everything that is happening inside will be broadcast outside,” Blanco affirms.

But the celebrations are not limited to the contest. Before this a supper will be held in the restaurant with some of Cuba’s most important chefs and sommeliers. On October 3 there will be a gala supper which will be attended by personalities and special guests.

Also around those days there will be the launching of a new Havana Club premium white rum to make the daiquiri and the opening of the Constante bar – named thus as a tribute to Constantino Ribalaigua – will take place in the Gran Hotel Manzana Kempinski. The Floridita’s maestro bartenders will be in charge of the inauguration of the new place.

This is how the old Havana bar will celebrate its two centuries. The same one that in 1992 received the Best of the Best Five Star Diamond Award, of the American Academy of Gastronomic Sciences, and which throughout its history has received figures like Graham Greene, Rocky Marciano, Tennessee Williams, Francis Ford Coppola, Marlene Dietrich and Paco Rabanne.

At No. 557 Obispo Street, a few meters from the Parque Central and the Grand Theater of Havana, the Floridita awaits, with the magnificence of its 200 years and the everlasting invitation of its daiquiri.

The recipe of its famous cocktail is its best invitation.

Floridita Daiquiri (Classic)

1 teaspoon of sugar

¼ ounce of lime juice

1 ½ ounce of three-year Havana Club rum

5 drops of maraschino

4 ounces of shaved ice

Mix for 30 seconds in a blender and serve in a cup with a straw