One week after the lifting of a group of restrictions, in force until then to contain the spread of COVID-19, Havana has a different face. It’s not only about increased activity in the streets, which there is, or the return of the buses to the urban landscape, or other opened shops, offices and restaurants and other businesses, but also about the people’s attitude, in the way in which they begin to assume their “new normal.”

“You have to adapt, there’s no other way,” said to OnCuba Luis, an electronics technician and owner of a home appliance workshop which he hopes to reopen “in these days” to improve his personal economy, affected by the pandemic.

“I already reopened it in July, when the coronavirus situation improved, but I preferred to close it when we went back, because the risk was high and health always comes first,” he explains. “Now I’m letting a few days go by to see how everything is going, but I’m ready to start, yes, taking extreme hygiene measures because the disease is not over and cases continue to appear in the city every day. But I have to, because if not, how do I feed my children? “

“I was dying for them to open,” Marisol, a domestic worker, says, “because these months have not been easy. I’ve had to live ‘inventing’ because I lost my job practically from one day to the next, and although taking out a license has been allowed and the payment of taxes has been postponed, one has to live on something, right?”

According to her, she has already been in contact with her regular clients, and although some asked her to wait for a while―“the coronavirus thing has been hard on many people,” she says―others have already given her the green light to start. Her greatest hope, she confesses, is that “the pandemic will end and tourism can return,” which would allow her to reconnect with a rental house where she worked regularly. “But in the meantime,” she says, “at least I can start doing something and making some money.”

However, although many have welcomed the de-escalation that began in October, there is no shortage of misgivings and concerns among Havanans. The government of the Cuban capital recognized it a few days ago on the television program Mesa Redonda. Then, the deputy governor of Havana, Yanet Hernández, cited among the aspects that have generated the most controversy in the population the reopening of beaches and swimming pools, the return of public transportation to 80% of its capacity and the announcement of the restart of the school year next November 2.

In response, Hernández confirmed that the reopening that the city is experiencing “constitutes a challenge and a big one, because we know that the possibility of contagion is high,” but reiterated the Cuban government’s recent discourse during these times―emphasized this Thursday by President Miguel Díaz-Canel when presenting to the country the update of the strategy to confront COVID-19 on the island—, stressing that this new normal demands “greater individual, family, community, collective and institutional responsibility in complying with the hygienic sanitary actions.”

In the end, the economy

The words of the Havana deputy governor respond to the approach currently being used by the island’s authorities in the face of the pandemic, a perspective that modifies the strict methodology designed for the first de-escalation in June and July, and which has now had a polygon of proof. It is a more pragmatic strategy, based on the idea of forced coexistence with COVID-19―in which the provisions established so far for the transmission and recovery stages are adapted―in tune with what happened in other nations; which preserves the emphasis on prevention, surveillance and epidemiological control and medical care as strengths of the Cuban system, and which, at the same time, reinforces the responsibility of citizens.

“We have to take care of ourselves a little more in our homes and workplaces,” Governor Reinaldo García Zapata told the people of Havana on September 30, announcing the relaxation of restrictions in the capital. “It must be assumed with commitment,” he said then, and assured that now “the active and responsible participation of each person, family and community plays an important role to achieve the results we hope for.”

For his part, Cuban President Miguel Díaz-Canel, along with a call to continue working with “great rigor” in the health system and other state institutions and centers, has also repeatedly appealed in recent days to “individual, family, collective, community and social responsibility.” This, he said, has to “be constant,” because “by sharing responsibilities we can continue to advance towards a more favorable situation in Havana.”

According to the president and other government figures, the reopening in the capital―as part of the new national plan for the pandemic―is due to the results of the health strategy and the restrictions applied, and to the experiences accumulated during seven months in the confrontation with COVID-19, which have not only made it possible to achieve an improvement in the indicators but also a lesson for the effective management of the disease. And they are right.

If the statistics and epidemiological scenario of Cuba are compared with that of most of the world, the good management of the epidemic in the country is obvious, even when the transmission of the coronavirus has not been eradicated and several provinces have experienced a regrowth in the summer months. The success of surveillance and containment measures and medical protocols, the work of health and scientific personnel, and the government’s organization and monitoring of actions against COVID-19, have prevented an explosion in the number of infections and collapse of hospitals and intensive care units, and have kept mortality rates low on the island.

Why has Cuban biotechnology been successful against COVID-19? (II)

However, as we already pointed out in the first part of this work, this change in approach and strategy undoubtedly has an economic background. A background that the Cuban authorities themselves have not hidden and that gains greater prominence in a context of economic crisis fueled by the impact―national and global―of the pandemic, the increase in U.S. sanctions and embargo, and structural problems and chronic inefficiencies of the domestic economy, which led President Díaz-Canel to recognize this Thursday that it is necessary to “give a greater push” to the implementation of the economic strategy recently approved by the government to alleviate the crisis.

Days ago, in one of the government meetings to assess the situation of the epidemic on the island, the president affirmed that “right now, we can’t continue with the same level of confinement, since it’s necessary to reactivate life” and pointed out that “people also need to reorder their economic and working life, just as we require that various institutions reactivate so that there is a higher level of services and goods to offer the population and thus our economy begins to perform differently.”

The numbers speak for themselves. As reported by the Havana deputy governor, only in the capital until the announcement of the new de-escalation did the expenses associated with COVID-19 exceed 125 million pesos, broken down into items such as food, transportation, medications and personnel expenses, among others. In addition, the income not reported to the State Budget amounted to a not inconsiderable 621 million pesos, 13% of what was planned; while the expenses for social assistance and salary treatment for people who left their jobs during confinement, and the costs for hospitalized patients, admissions to isolation centers and diagnostic kits, deepened the black hole of the state coffers.

To give you an idea, as exemplified by Hernández, only in August the cost of hospitalized patients in Havana was around 3 million pesos, while that of those admitted to centers for suspects exceeded 930,000. It’s not surprising then that the new plan against COVID-19 in Cuba, presented this Thursday, contemplates for the “new normal” the home isolation of contacts of confirmed and suspected cases—except for vulnerable people and other exceptions—, and not in hospitals or isolation centers, a characteristic that had distinguished the Cuban strategy until now. The same will happen with nationals arriving from abroad, who will no longer have to undergo a quarantine in a state institution, but will be monitored in their homes by primary health care, while tourists will go to their hotels to wait for the result of their respective PCR tests.

*Caption:

COVID-19

ECONOMIC IMPACT IN HAVANA

Expenditures associated with the pandemic: 125 million pesos

- In food: 7 million

- Medicines: 10 million

- Linen items and garments, toiletries and cleaning: 3 million

- Personnel expenses: 65 million

- Transportation: 13 million

- Social assistance: 2 million

Cost per hospitalized patient: 785.75 pesos

Cost per patient in centers for suspicious cases: 343 pesos

Cost per diagnostic kit: 67.39 pesos

Income not reported for the state budget

621 million pesos

Of phases, changes and figures

If we discount the new cases reported this Friday―corresponding to the close of the previous day―, until the first week of October, Havana added 3,321 patients detected with COVID-19, 56.1% of the total in Cuba. Since the arrival of the coronavirus to the island, the capital has been the epicenter of the epidemic, even though it has fluctuated between peaks and plateaus, between declines and outbreaks, and, consequently, it has gone through different periods until reaching the de-escalation in progress these days.

A look at various epidemiological indicators of the city in recent months, in particular the moments prior to the changes in phases and strategies for coping with the disease, allows us to verify not only its evolution in the Havana geography, but also the interpretation of its development by the population and the government, the approach taken by the authorities to apply measures or lift restrictions, based on the experience acquired and without neglecting the aforementioned economic component.

In this way, it is not difficult to discover that if for the capital’s transition to phase 1 of the recovery at the beginning of July, according to the previously applied methodology, it was waited until the figures fell considerably―and yet, a part of the population thought it was precipitous―, for the current reopening the indicators were interpreted in a more pragmatic way and, even so, their reception by Havanans, exhausted after seven months of the pandemic and, in particular, after a month of harsh restrictions, seems to have been less alarmist.

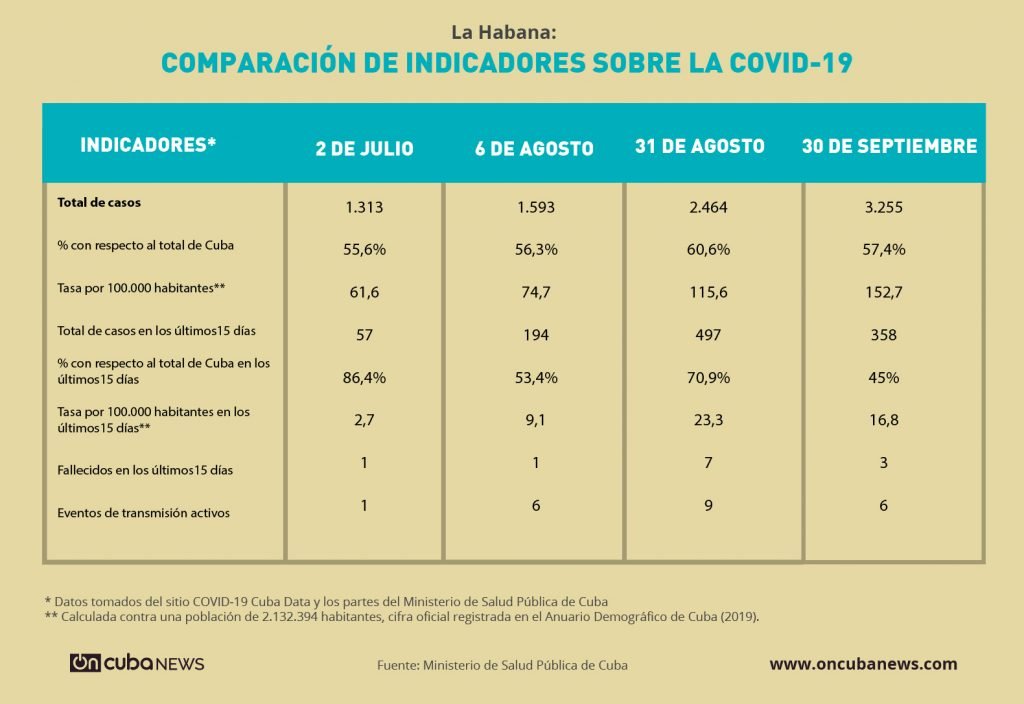

A simple count shows that if in the 15 days prior to the reopening that began on July 3, the new cases were only 57 and the rate per 100,000 inhabitants was 2.7, in the 15 days before the “flexibilization” of restrictions on October 1, these same indicators amounted to 358 and 16.8, even higher than those of the period prior to the decline decreed on August 7, and close, although lower, than when it was decided to impose the curfew and other restrictive measures as of September 1. However, this minor improvement, together with other important aspects, such as the number of deaths, outbreaks and active transmission events, was sufficient to lift bans and begin de-escalation, even with the city in the transmission phase.

*Caption:

Havana:

COMPARISON OF INDICATORS FOR COVID-19

INDICATORS JULY 2 AUGUST 6 AUGUST 31 SEPTEMBER 30

Total of cases

% with respect to Cuba’s total

Rate per 100,000 inhabitants**

Total of cases in last 15 days

% with respect to Cuba’s total in last 15 days

Rate per 100,000 inhabitants in last 15 days**

Deaths in last 15 days

Active transmission events

* Data taken from COVID-19 Cuba Data site and the reports by the Cuban Ministry of Public Health

** Calculated based on a population of 2,132,394 inhabitants, the official figure registered in the Demographic Yearbook of Cuba (2019)

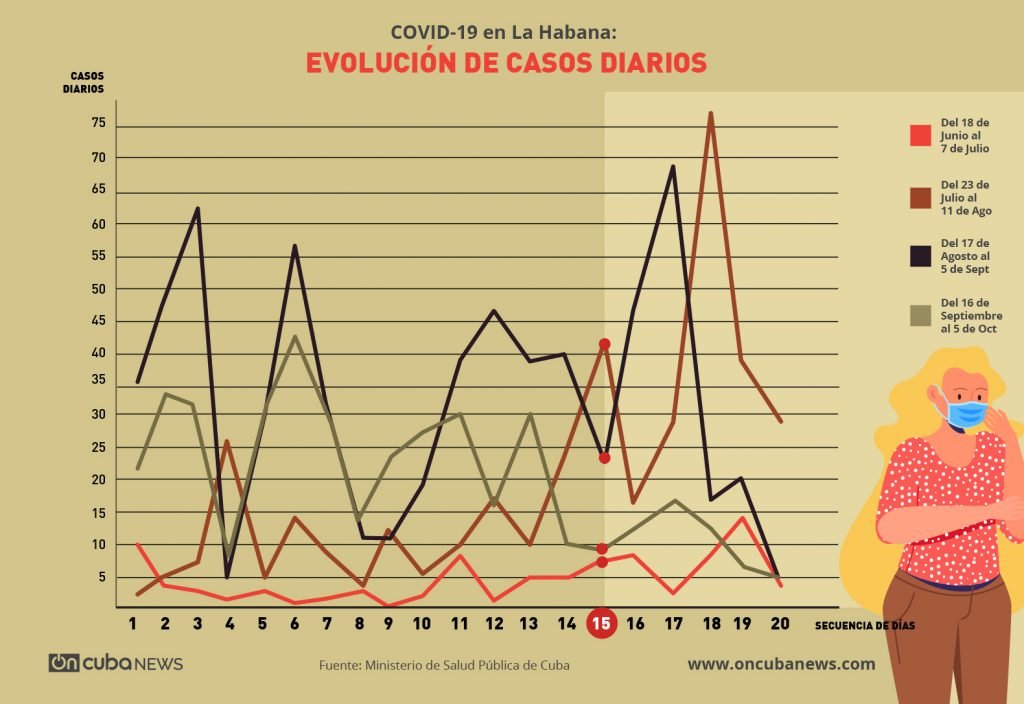

A comparison of the temporary sequences of these four moments prior to the changes of phases and measures decreed in Havana (from June 18 to July 2, before the transition of the city to phase 1 of the recovery; from July 23 to August 6, before the return to the limited autochthonous transmission phase; from August 17 to 31, before the application of more severe restrictions; and from September 16 to 30, before the dismantling of those restrictions), also makes it possible to check the similarities and differences between them, the peaks and drops in the number of daily cases that numerically verify the worsening or improvement of the epidemiological scenario.

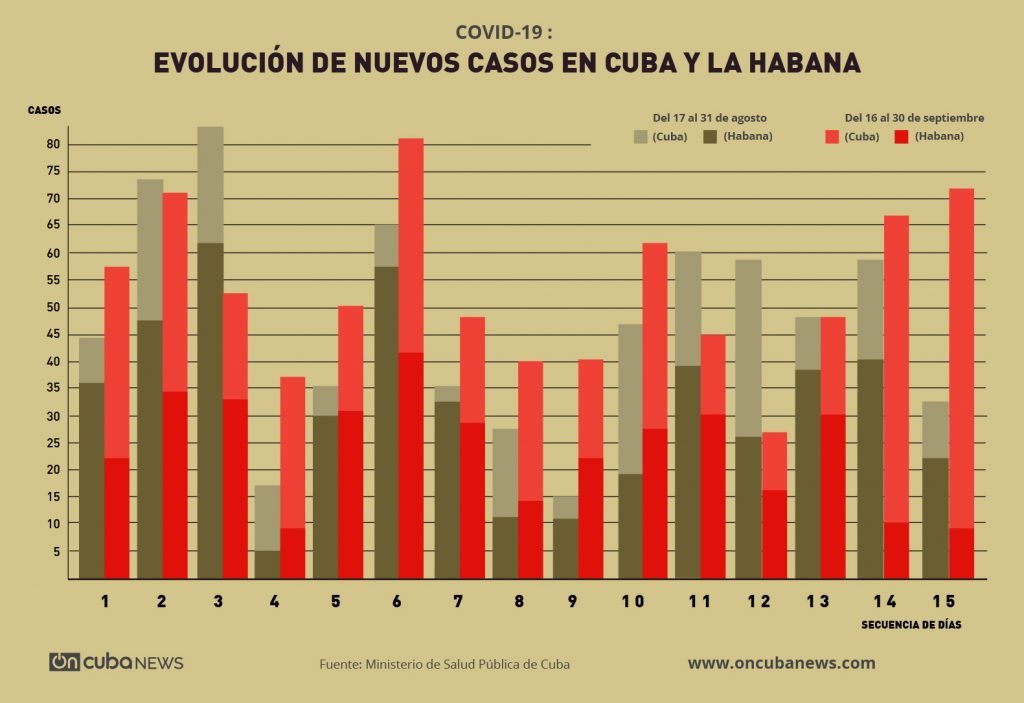

We have included in a chart another five days in these time sequences, after the date of the change, so that the early evolution of that scenario can be seen once the new phases and measures take effect. In addition, we also propose a graph focused only on the last two sequences (end of August and end of September), in which the divergences and similarities of both seemingly opposing periods can be verified―one that led to stricter restrictions and the other, to a lifting of these and other measures—, and also the weight that Havana had in both moments within the total number of new infections detected on the island.

*Caption:

COVID-19 in Havana:

EVOLUTION OF DAILY CASES

Daily cases

From June 18 to July 7

From July 23 to Aug 11

From August 17 to Sept 5

From September 16 to Oct 5

Sequence of days

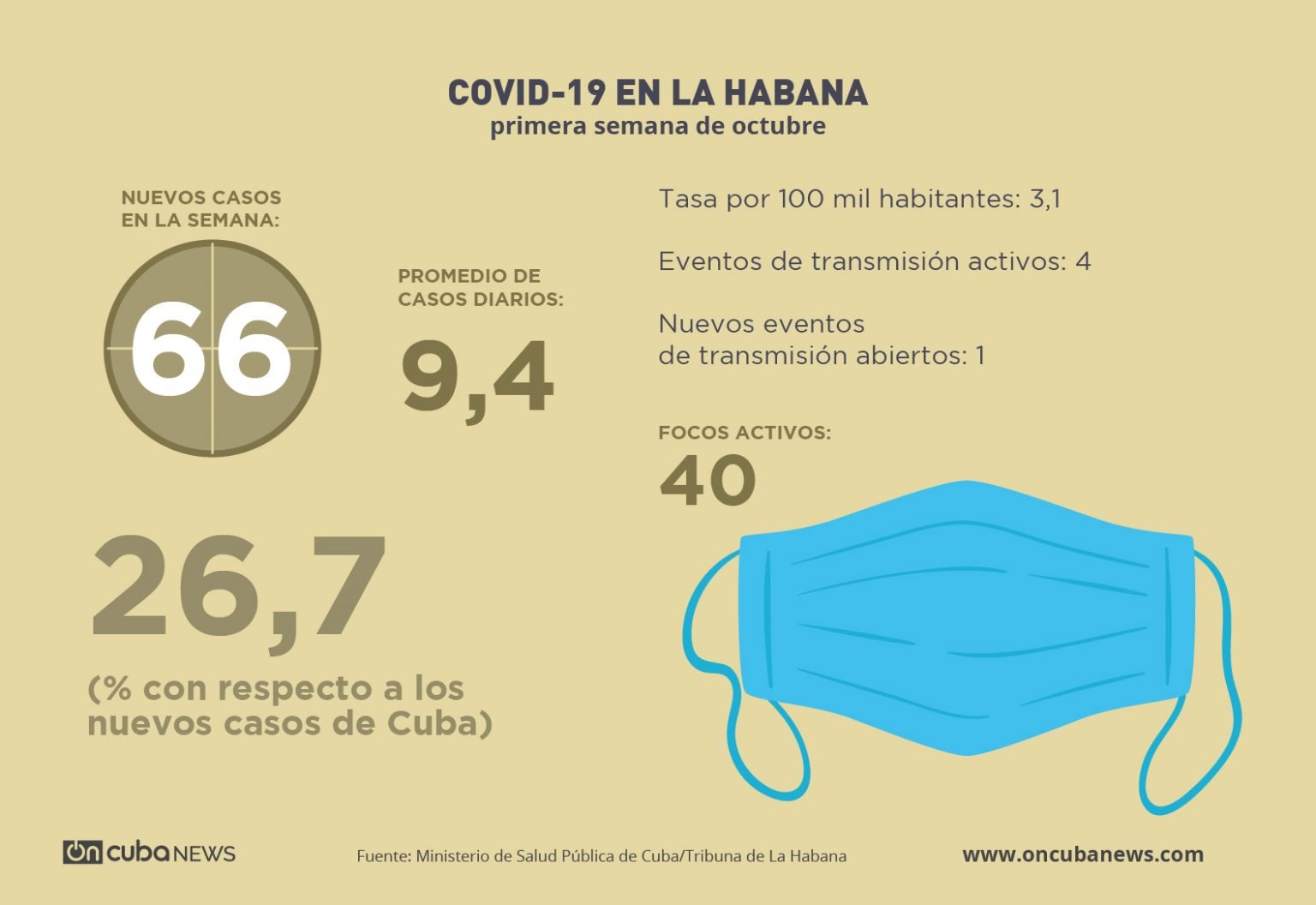

Finally, as a week has already passed since the beginning of the reopening in the capital, we propose a look at what happened in the city in this short period in which, judging by official figures, the situation has remained favorable. Thus, between October 1 and 7, the city of Havana registered 66 detected contagions (26% with respect to new cases in Cuba), a daily average of 9.4, and a rate of 3.1 cases per 100,000 inhabitants. In addition, at the close of this Thursday, 40 outbreaks and four transmission events were active, one of them opened in the last week. However, even when the statistics reveal a positive scenario, the 20 new cases reported this Friday make the alarms go off again and give the reason to the Havana authorities and their call to “not lower our guard” in the face of the constant danger posed by COVID -19.

*Caption:

COVID-19

EVOLUTION OF NEW CASES IN CUBA AND HAVANA

CASES

From August 17 to 31

Cuba Havana

From September 16 to 30

Cuba Havana

Sequence of days

*Caption:

COVID-19 in Havana

First week of October

Week’s new cases

Average of daily cases

Rate per 100,000 inhabitants: 3.1

Active transmission events

New open transmission events

Active outbreaks

(% with respect to Cuba’s new cases)

Starting next Monday, according to what was announced this Thursday by Prime Minister Manuel Marrero on Cuban television, Havana will cease to be in the limited autochthonous transmission phase and will enter phase 3 of the recovery stage. An Olympic jump based on the indicators it currently shows, which, according to what Marrero explained, have been specially modeled for the capital taking into account its complexities and differences with respect to the rest of the island.

This means that, in accordance with the new Cuban strategy against the pandemic, the city will not yet officially be in the “new normal,” a category for those territories with a better epidemiological situation and which almost the entire island will enter next week, except for Havana and the central provinces of Ciego de Ávila and Sancti Spíritus, which are currently the most affected by the coronavirus. However, the passage to this phase could take place at any moment if circumstances improve, or, on the contrary, a new setback could be experienced, if measures are neglected and contagions increase again in the city of Havana. A possibility that cannot be lost sight of and that demands everyone’s commitment—of the government and citizens, state entities and private businesses—, even though for the people of Havana the idea of what is “normal” will never be the same.