The electoral authorities of Cuba reported the official data of the referendum on the Family Code that took place on September 25. It had already been announced that the results determined the approval of the new Law, which was endorsed by the highest Cuban authorities.

The scourge of powerful Hurricane Ian in western Cuba, just two days after the voting, and the arduous recovery work still underway, delayed the officialization of what was already known: the victory of the “Yes” at the polls, both on the island as in the Cuban missions abroad, which, added to the previous support of the National Assembly, gave the Code the legal validity required for its entry into force.

In this way, despite not a few controversies and re-elaborations — the one approved in the referendum was version 25 —, the regulation officially became law with its definitive publication in the Gaceta Oficial de la República on September 27, with which its broad and innovative articles are already in force, including the issues that aroused the most controversy in the population, such as same-sex marriage, adoption by homosexual couples, solidarity gestation and the progressive autonomy of minors.

For this to be possible, support for the Code had to obtain a simple majority of the votes, that is, for more than 50% of the voters who would go to the polls to vote in favor of the text, something that, in effect, happened, according to the figures offered by the National Electoral Council (CEN) of Cuba.

“Who said everything is lost?” The referendum and its legacy

In short, the final data released hardly differs from that offered a day after the referendum, when thirty districts remained to be accounted for — after the closure of a group of colleges was postponed in several territories due to the occurrence of rains — and the CEN validated the “Yes” victory due to the “irreversible trend” in favor of this option.

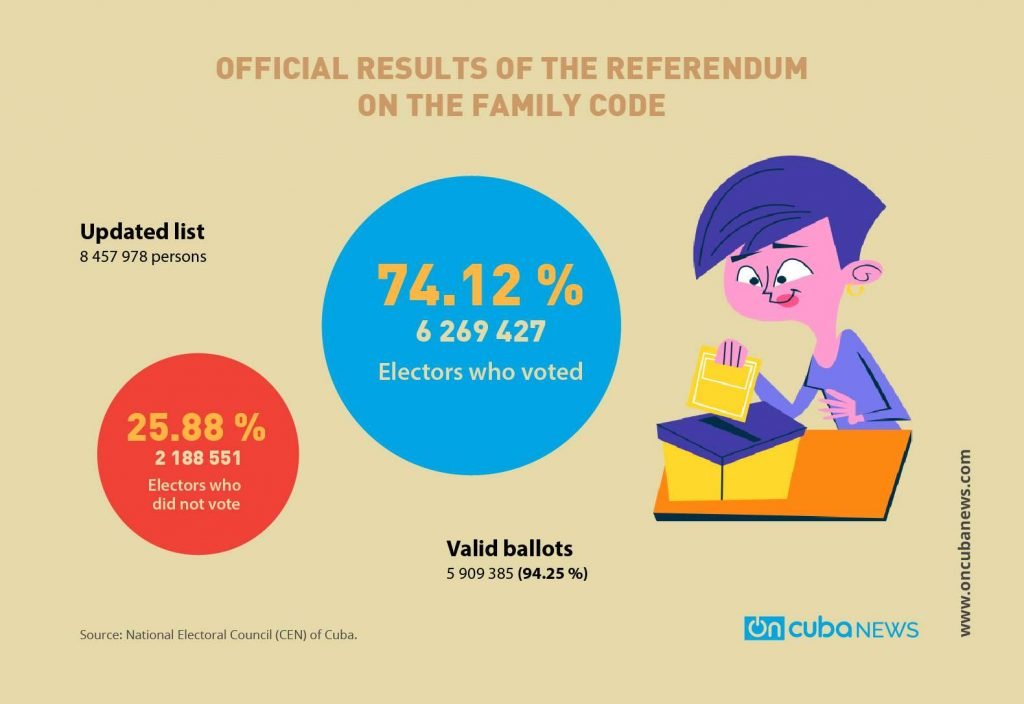

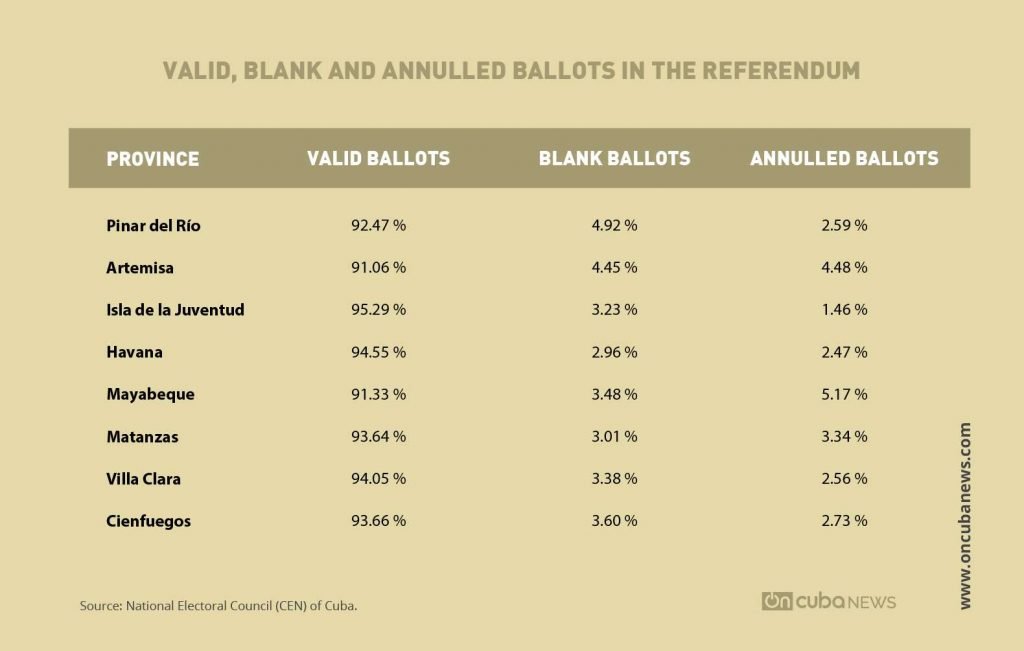

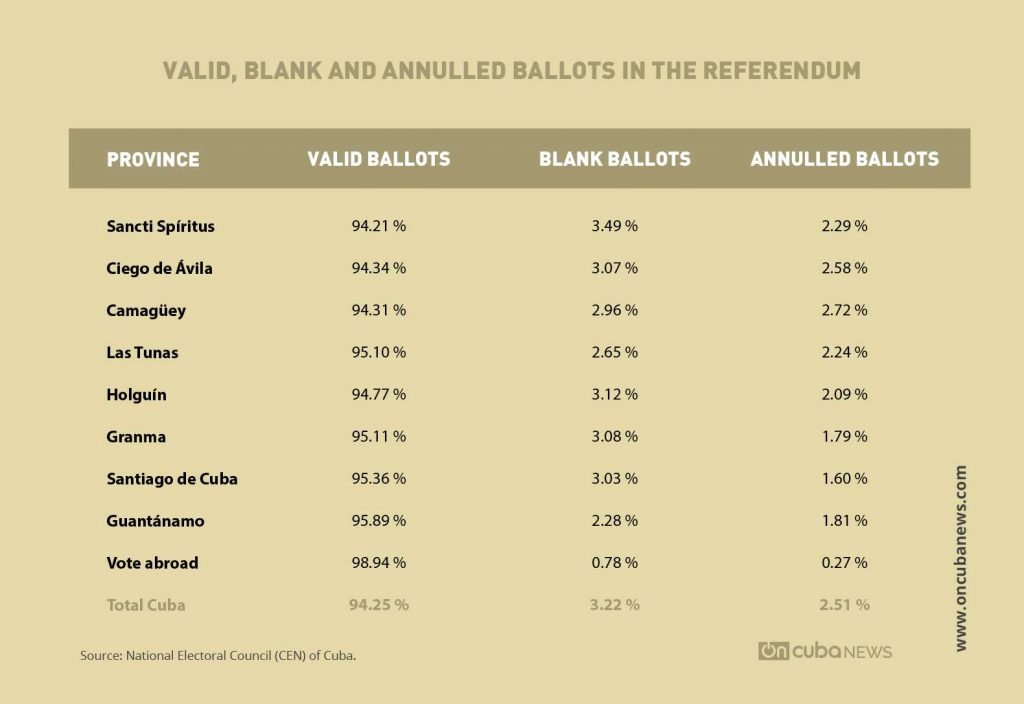

After updating the electoral list, resulting in 13,058 inclusions for various reasons and 2,547 exclusions due to death, it was finally made up of 8,457,978 voters, more than 10,000 more than those initially registered. Of these, more than 6.2 million turned out to vote, 74.12% of the updated list, of which 5.9 million (94.25%) cast valid votes.

Meanwhile, even though the CEN did not provide the data, a simple calculation is enough to know that more than 2.1 million people, 25.88% of the final list, did not show up at the more than 23,000 colleges throughout the country, of them 224 “special,” because they are located in hospitals, terminals, hotels and other places of great concentration of people “to facilitate access to the vote,” according to the electoral authorities.

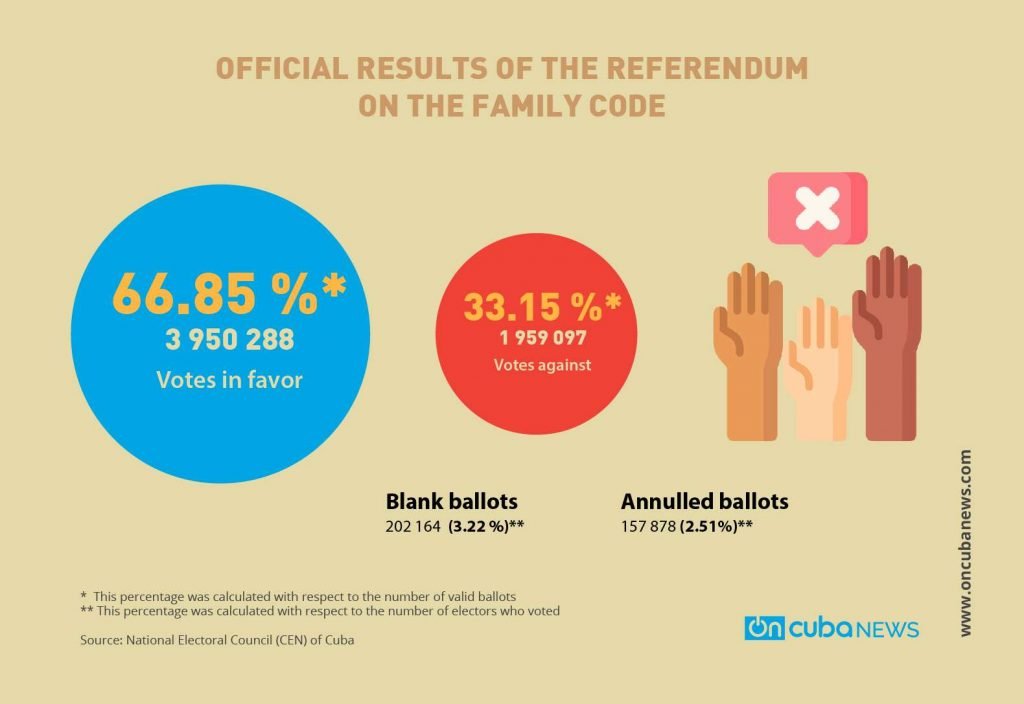

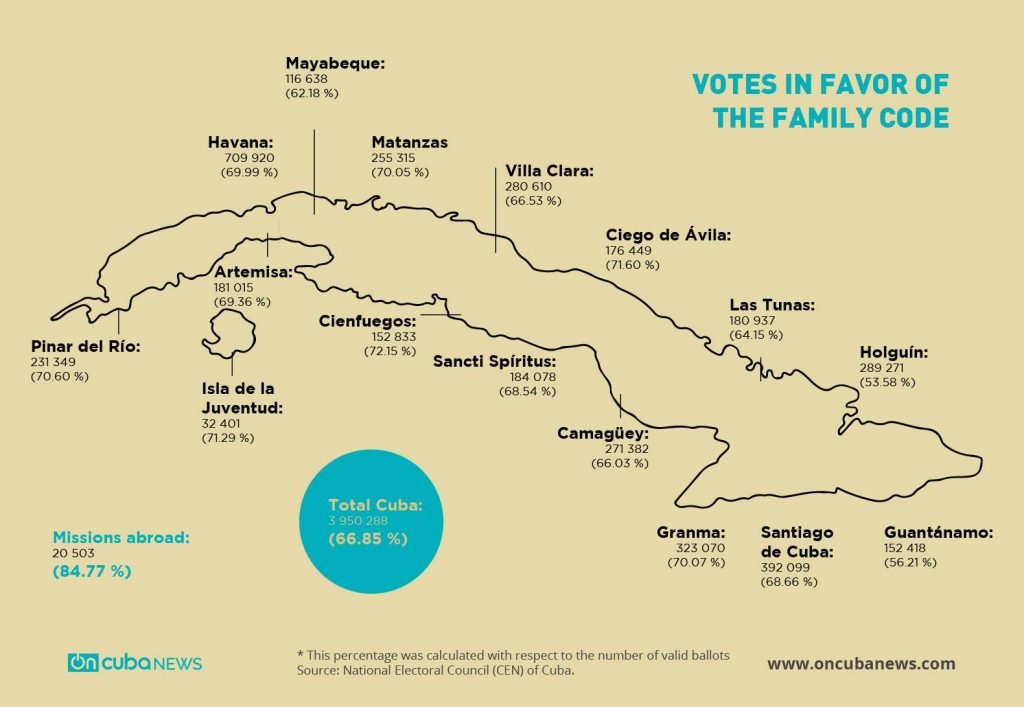

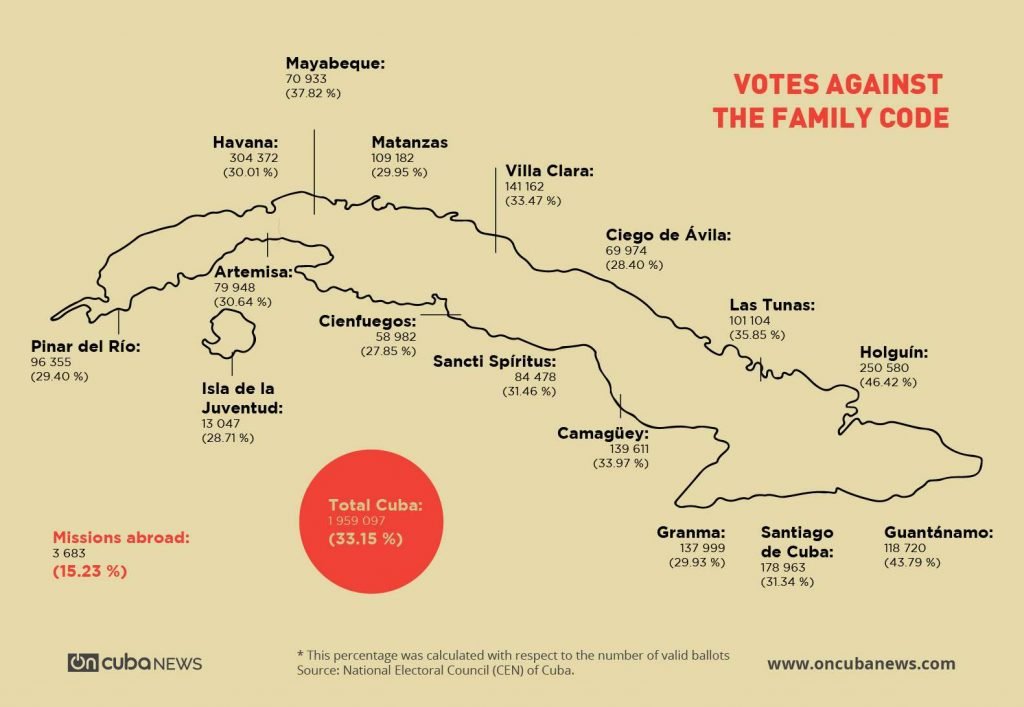

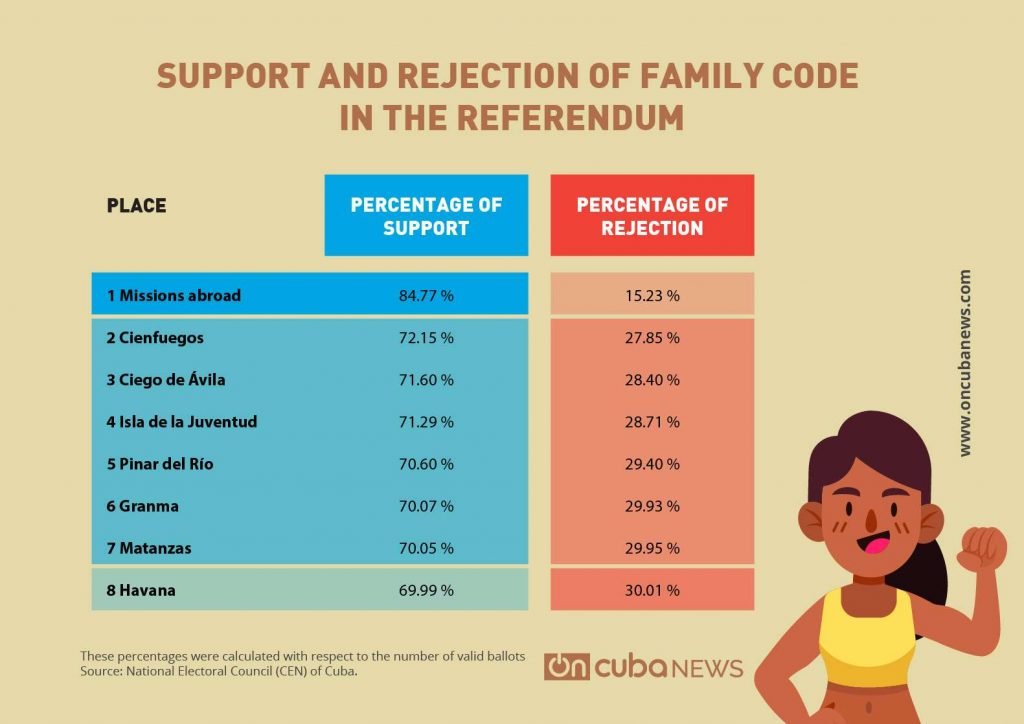

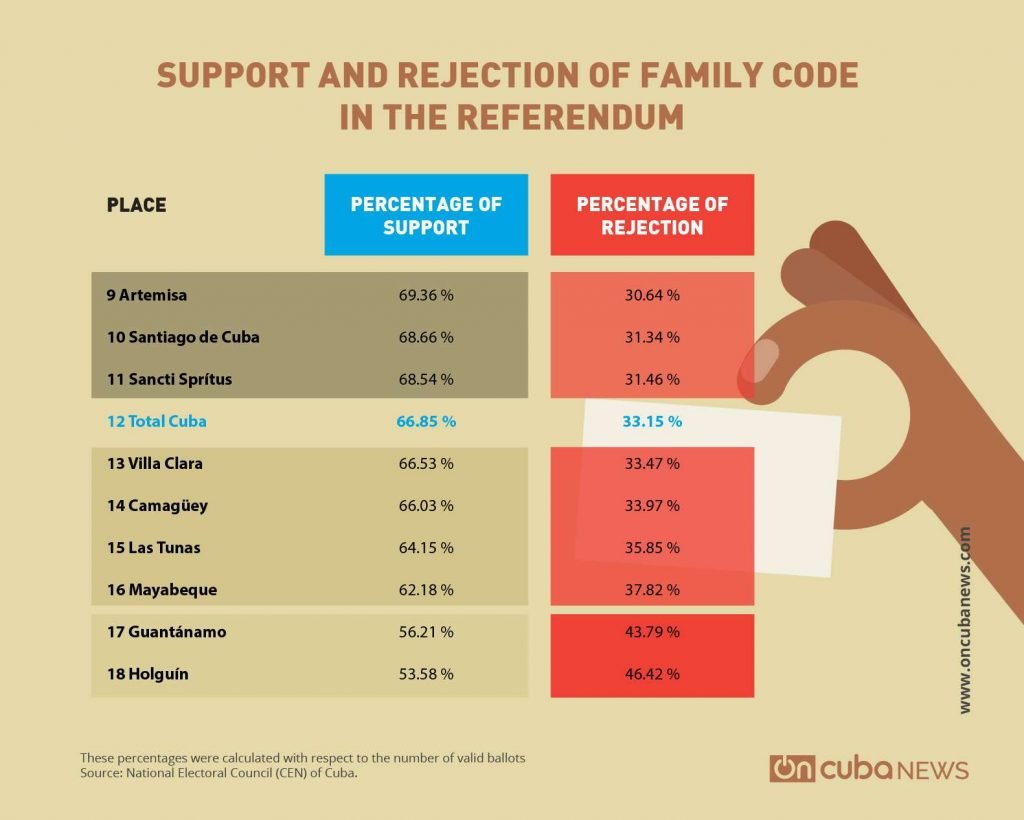

Of those who voted, 3.95 million gave their support to the Code, 66.85% of the valid votes, while just under 1.96 million rejected it, 33.15% of those who did not cast empty or annulled ballots. The latter represented 3.22% (blank) and 2.51% (null) of the voters who participated in the referendum.

As for the percentages of those who supported or opposed the regulation, it is not idle to note that these decreased slightly to 63% and 31.24% if they are calculated with respect to the total number of voters who voted, a criterion used by the CEN in its official statistics of the 2019 referendum, in which the population validated the current Magna Carta of Cuba.

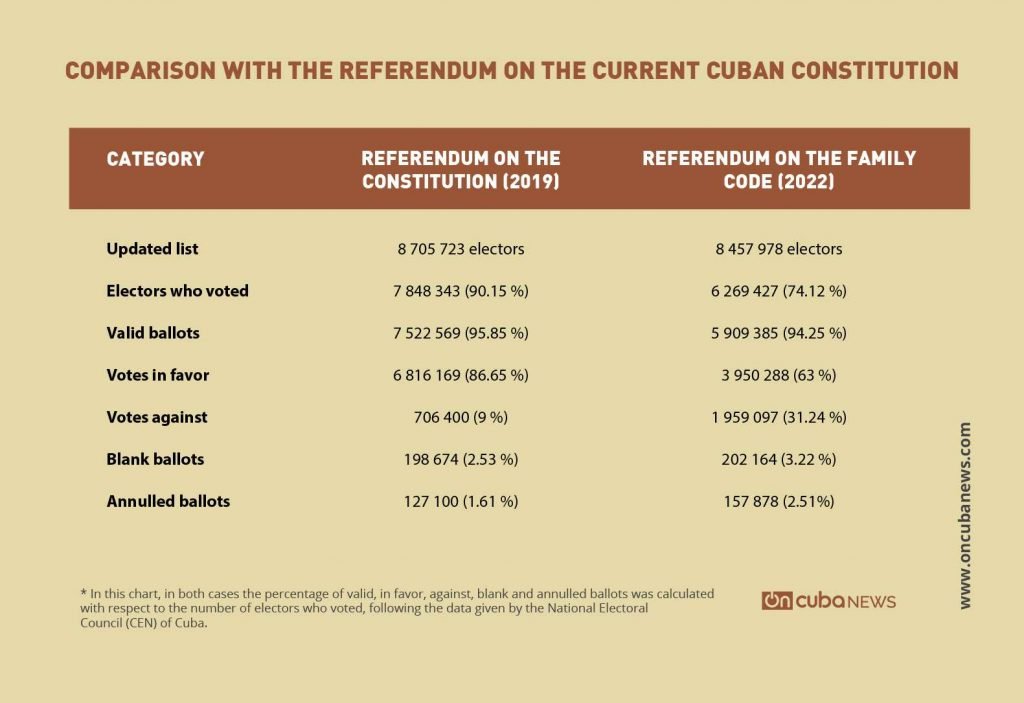

A comparison between the two processes, moreover, makes it possible to show not only the decrease in just three years of the electoral list of almost 250,000 people — at a time when the island is going through a strong and sustained migration wave —, but also a significant increase in abstention — the participation rate fell from 90.15% to 74.12%, high, without a doubt, when compared to other elections in the world, but low compared to the electoral processes of recent decades in the Caribbean nation — and a greater opposition to the options promoted by the government, in both cases the support for the texts, beyond the possible interpretations for it.

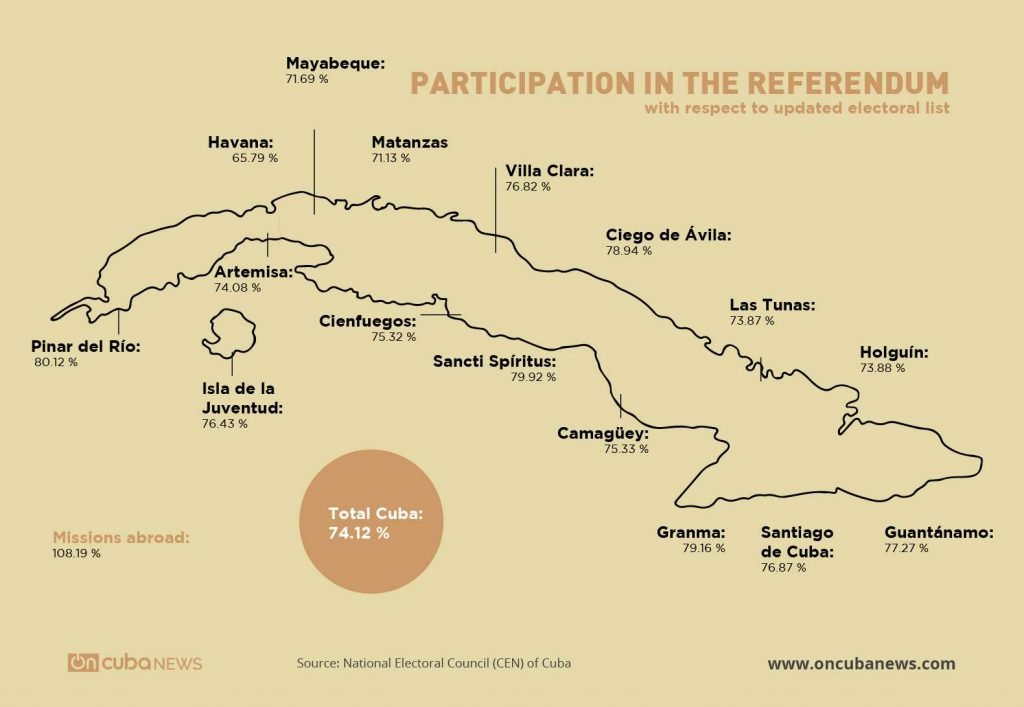

In addition to the updated general data, the CEN offered this week the results in the different provinces, including the special municipality of Isla de la Juventud and also the official Cuban missions abroad —diplomatic, health, educational, sports and others —, whose members had the opportunity to vote a week before, unlike the rest of the Cubans residing outside the country, who in order to do so had to be in Cuban territory on September 25.

In the case of the missions abroad, it is also important to highlight that, as reported by the CEN, they had a participation rate of over 100% because on the day of the vote in the different countries there were “collaborators who were not initially foreseen in the basic report issued.” Similarly, this group stands out for registering the highest percentage of valid ballots (98.94%), the lowest percentage of blank and canceled ballots (less than 2% between the two) and the greatest support for the Code (84.77%), the only one that was over 80%.

Regarding participation on the island, with the exception of Havana where it was 65.79%, in the rest of the provinces it was over 70% — Pinar del Río led with 80.12% —, while more than 90% of the voters of all the provinces who exercised their right cast valid votes.

Regarding support and rejection, and apart from what was already mentioned about official missions abroad, the former oscillated mostly between 70 and 60%, with only Holguín (53.58%) and Guantánamo (56.21%) below this percentage, and in the second the exact opposite occurred — between 30 and 40% —, with these two eastern provinces leading the opposition to the new legislation.

Unfortunately, the numbers released this week do not delve beyond the provincial values, which does not allow us to know what happened at the municipal level and in specific localities. This, without a doubt, would have enabled a more stratified view of the popular position on the Code, and would have facilitated a more accurate analysis by region or according to the nature of the communities.

A more detailed interpretation of the results would also have been possible if it was known how the vote was carried out by age groups, gender, educational level, social origin and other demographic and sociocultural categories, but the legitimate direct and secret character of the vote and the existence of previous or at polls surveys — with the margin of inaccuracy that they suppose — do not shed light in this direction.

Despite this, the data by provinces give the possibility of looking beyond the general statistics and contributing to better understand and, as far as possible, interpret what happened at the polls. With these figures organized in order from highest to lowest (support) and from lowest to highest (rejection) we then close this compendium of the data offered.